The Lens of John H. White: A View of Black Life in Chicago, 1973

Photo essay by Steven D. Booth

In his speech, “Using Federal Archives: Some Problems in Doing Research,” Nigerian historian Okon Edet Uya notes that federal records often “describe the Afro-American experience from the outside in rather than from the inside out…this has led to a situation where Afro-American history, for some, is nothing more than the sum total of the conflicting activities of the various government levels for or against [B]lack people.” He goes on to suggest that other methods, such as eyewitness accounts, should be used to fill critical gaps that are missing from these often one-sided narratives, as through those eyewitness accounts that the stories of the Black experience can be “collected from people who observed or participated in the historical process described” in the records. One example of such a historical process is the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) DOCUMERICA Project, in particular the photographs contributed by noted Black photojournalist John H. White.

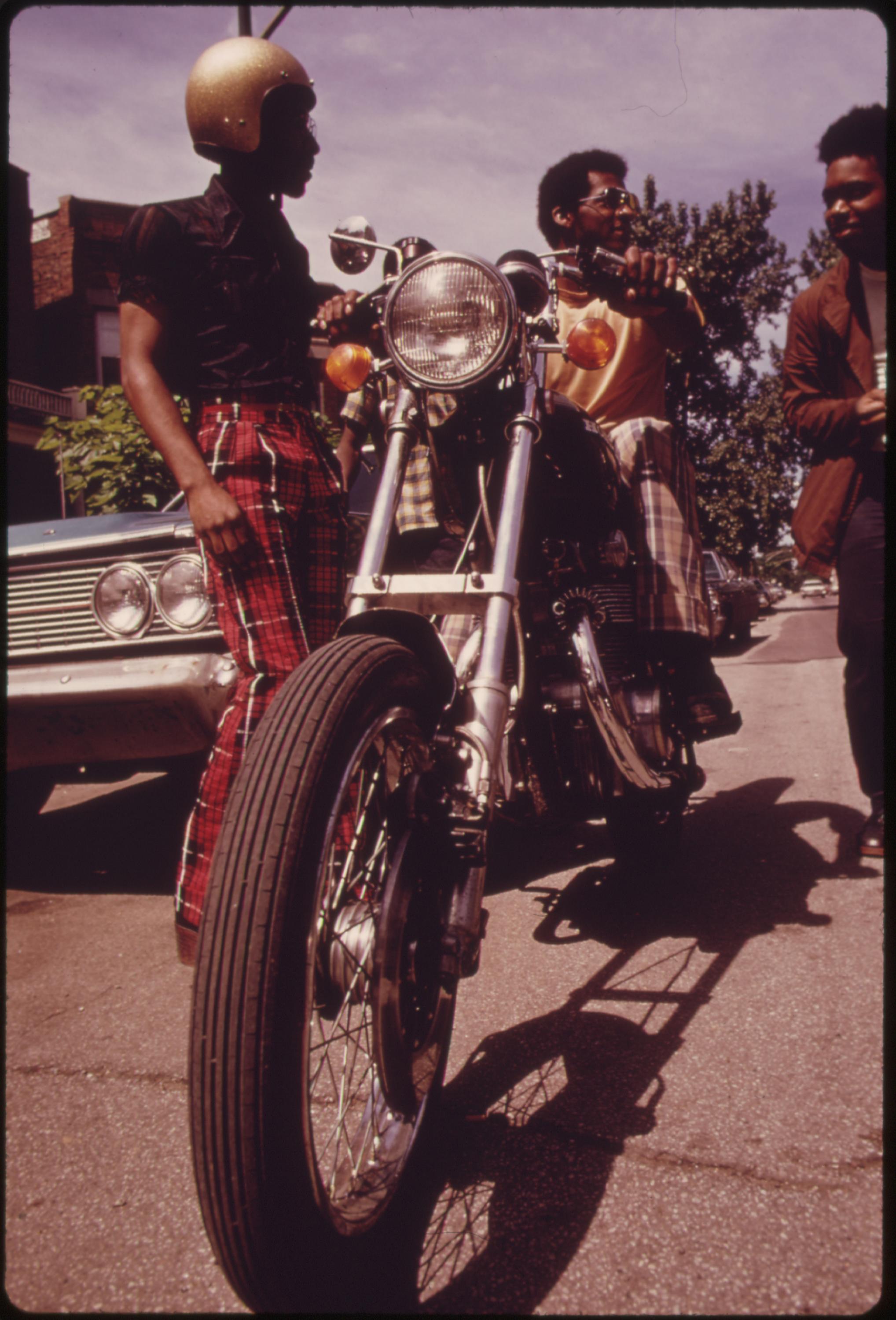

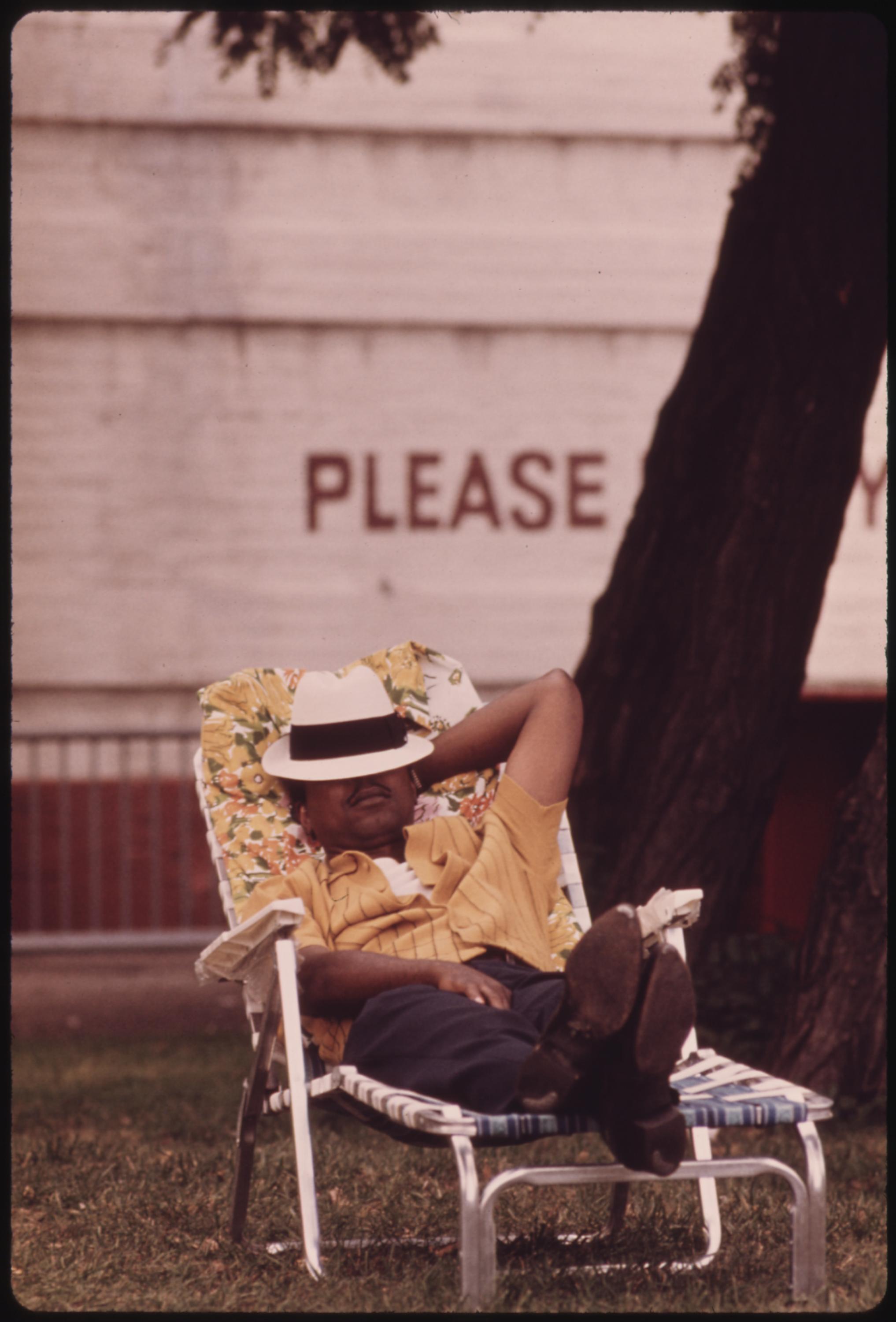

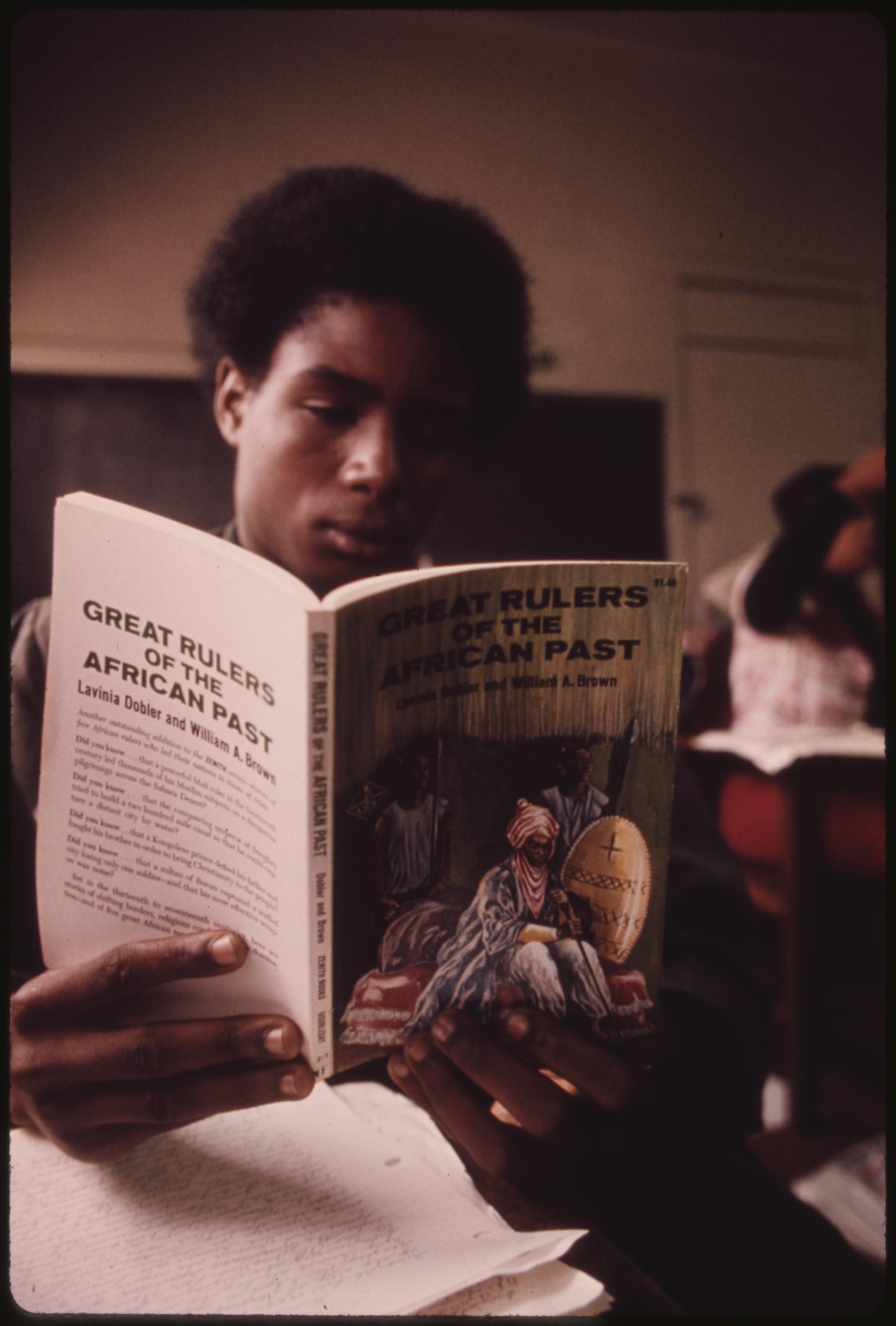

White was hired as one of many freelancers to document the environmental challenges of the 1970s in the US, and he journeyed across the South and West sides of Chicago documenting everyday Black life through photography. His images capture the people, events, and places—some of which are no longer extant—that highlight the rich history and unique culture of Black Chicagoans. Apart from the photographs, their subjects, and visual qualities, what’s notably interesting about this body of work is White’s captions. Unlike other photographers, he describes his subjects with an intimacy and familiarity that acknowledges their lives and livelihoods. Rather than leave the description to viewer interpretation, White provides context to help us understand who and what we’re seeing. His use of data from local and federal reports underscores some of the disparities Black people face and lack of resources in our communities, many of which persist to this day. White’s eyewitness account, as a Black man capturing Black experiences, asks us to consider that the economic conditions and material environments of those photographed are not of Black people’s individual making. Indeed, White’s portrayals of Black Chicagoans are suffused with historical and political consciousness. He shows us that despite our circumstances and surroundings, Black people have and continue to not only survive but also thrive in the face of adversity.

The photos are displayed with their original captions.

White was hired as one of many freelancers to document the environmental challenges of the 1970s in the US, and he journeyed across the South and West sides of Chicago documenting everyday Black life through photography. His images capture the people, events, and places—some of which are no longer extant—that highlight the rich history and unique culture of Black Chicagoans. Apart from the photographs, their subjects, and visual qualities, what’s notably interesting about this body of work is White’s captions. Unlike other photographers, he describes his subjects with an intimacy and familiarity that acknowledges their lives and livelihoods. Rather than leave the description to viewer interpretation, White provides context to help us understand who and what we’re seeing. His use of data from local and federal reports underscores some of the disparities Black people face and lack of resources in our communities, many of which persist to this day. White’s eyewitness account, as a Black man capturing Black experiences, asks us to consider that the economic conditions and material environments of those photographed are not of Black people’s individual making. Indeed, White’s portrayals of Black Chicagoans are suffused with historical and political consciousness. He shows us that despite our circumstances and surroundings, Black people have and continue to not only survive but also thrive in the face of adversity.

The photos are displayed with their original captions.

![South Side Black workers passing the time playing checkers on East 35th Street before going to work in Chicago. The city census figures show a significant gap in economic security between Blacks and whites. Median Black income between 1960 and 1970 increased from $4,700 to $7,883 but the dollar gap between the two races widened. Blacks were receiving [an] average of $3,603 less than the median white family, May 1973.](https://freight.cargo.site/t/original/i/ead5621acf86ba11845a1ceb0da77e3dccaf31ef7af5b7501c4810ff42d852a5/Booth_PhotoEssay_001a.jpg)

![Once one of Chicago’s busy thoroughfares, 63rd Street has changed with the character of the city. Many fires have resulted [in] driving out more businesses which either follow the flight of other stores to more prosperous areas or cease to exist. The “El” (elevated train) tracks are seen in the upper portion of the picture. During 1973 the Chicago Transit Authority reported 95,160,535 passengers used the facilities, July 1973.](https://freight.cargo.site/t/original/i/21c611093bafe4b65afca9f8c4a9a50970a320cd25172a31057b371ab4b4e7b7/Booth_PhotoEssay_CTA.jpg)

![The Kadats of America, Chicago's most loved young Black drill team shown performing on a Sunday afternoon at a community talent show on the South Side. [The] leader of the group is Major General Acklin who works with the youngsters to give them a positive outlook on life. The group has won many marching and drill awards, and has performed in many area parades, August 1973.](https://freight.cargo.site/t/original/i/262dca5fc52f9f8e24a6c39eda044689ac99471e0587ac25f5933b66d4f1eec4/Booth_PhotoEssay_001o.jpg)

![Black soul singer Isaac Hayes performs at the International Amphitheater in Chicago as part of the annual [Operation] Push “Black Expo” in the fall of 1973. The annual event showcases Black talent, educational opportunities, stars, art, and products to provide Blacks with an awareness of their heritage and capabilities, and help them towards a better life, October 1973.](https://freight.cargo.site/t/original/i/beffe0f75d681f9d771d4579b152c2718c84711d111903de1ed62f3be45b32ca/Booth_PhotoEssay_001p.jpg)

Steven D. Booth (he/him) is an archivist, researcher, and co-founder of The Blackivists Collective. He has been with the National Archives and Records Administration since 2009 and currently manages the audiovisual collection for the Barack Obama Presidential Library. He is actively involved in the Society of American Archivists (SAA) and recently served on the governing board of the organization.