More than a Melody: Reimagining the Sounds of Blackness

Essay by Ireashia M. Bennett

When I was younger, music offered respite from my then-confusing and heavy reality. I felt very much like an outsider both at school and at home; my queerness was already enveloping me before I could fully claim ownership of it. Within this feeling of isolation, music became my solace and my first love.

My love for music does not stop at a song, an album, or a musician. This love is rooted in a deep curiosity. As a teenager, I loved to study and learn about different types of music. I would scour the internet for hours researching new genres. I read countless articles and watched hours of interviews with musicians describing their creative process, inspiration, and work. I would stay up until 3am searching through LiveJournal music blogs and forums, watching YouTube clips, listening to Last.Fm, illegally downloading whole discographies or making mix CDs to listen to on the way to and from school. I prided myself for developing an “ear” for music. If I was hooked on a song, I extended my love by understanding the historical, geographical, social, political, and cultural contexts of its music genre or culture. I was voracious in my yearning to know the various lineages within Black music: the differences between Chicago Blues and Delta Blues, what hip hop shares with punk, how who we are and where we come from influence the distinction in sound.

In other words, I am a HUGE music nerd.

When I discovered the Center for Black Music Research (CBMR) while studying Jamaican dancehall music for a class project at Columbia College, I thought I died and went to heaven. I never dreamed a place like this could exist.

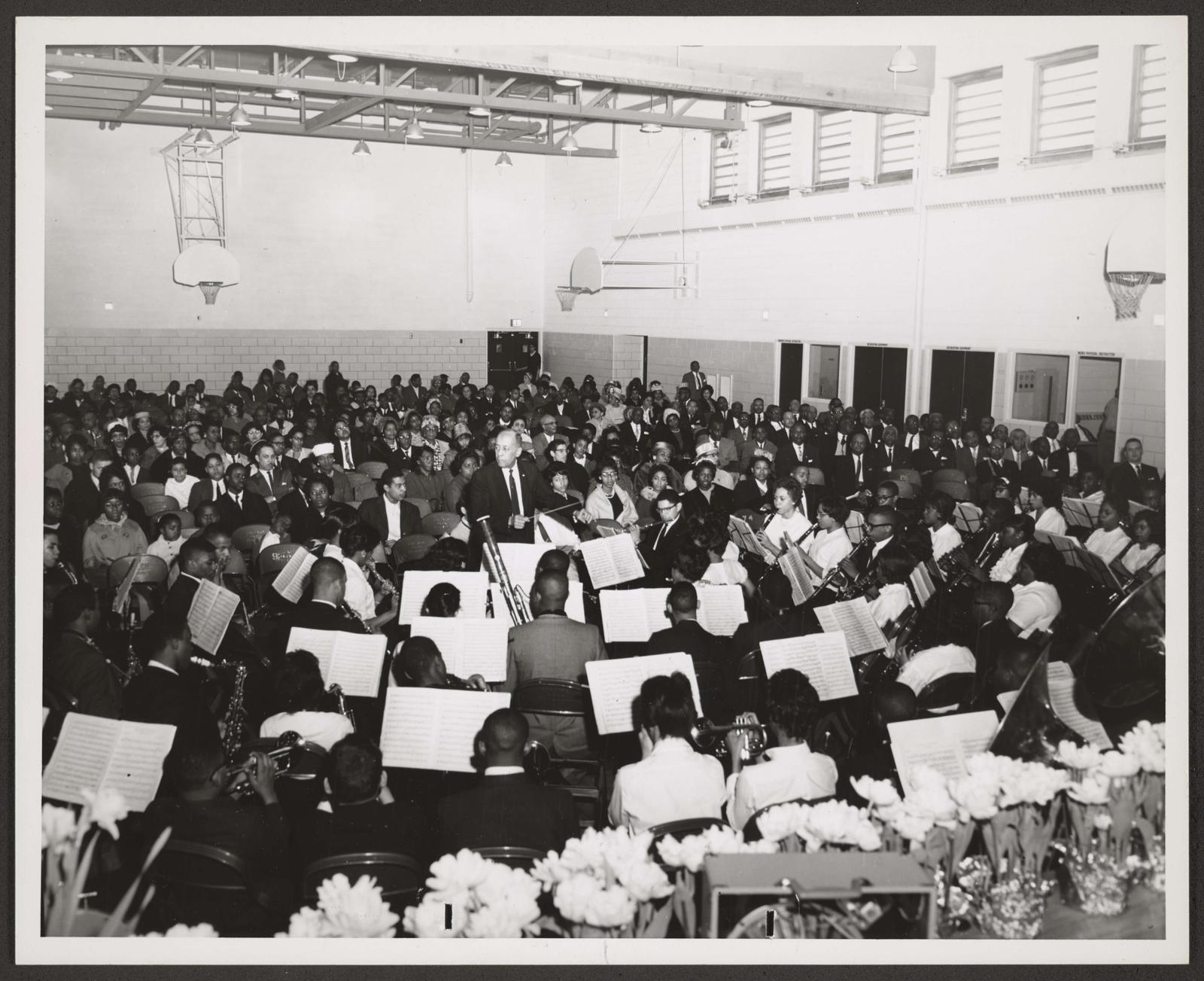

The CBMR, founded in 1983 by Dr. Samuel A. Floyd with his own personal collection, is a special collections archive meant to highlight the role Black music has played in the world. Later expanded in 1991 at Columbia College, the CBMR holds 47,000 sound recordings in all formats; over 100 individual archival collections over 15,000 scores, images, concert programs, and newspaper clippings; and 8,700 secondary resources, including books, dissertations, and serials. All the materials in the collection center the brilliance of African and Black musicians, music cultures, and histories originating from, or representing, the United States, Africa, Europe, Latin America, and the Caribbean. The CBMR was the only special collection like it at the time of its foundation. When I visited for the first time, I felt the magnitude of this fact.

From 2014 to 2016, the CBMR library became a sanctuary for me. The space itself was drab and not at all inviting, to be honest. But, the weight of knowledge that occupied its shelves drew me in. I learned so much during this time. How sacred it felt to exist within a space that expanded my understanding of not only Black music but also Blackness. I felt a sense of power and pride as I read about the African roots of Cúmbia music, the evolution of Jamaican reggae and dancehall in Puerto Rican reggaetón, and listened to the collaborations between bebop innovator Dizzy Gillespie and Afro-Cuban jazz musician Mario Bauzá. I was rediscovering Blackness. And, although these histories and cultures were different from my own, I felt welcomed and grounded by their Blackness. During my time at CBMR, I also learned that my obsession for music that began as an adolescent could become a career path in ethnomusicology if I chose. Before the age 23, I never heard that term or thought it possible to translate my love for music into the study of Black music cultures across the diaspora.

My love for music does not stop at a song, an album, or a musician. This love is rooted in a deep curiosity. As a teenager, I loved to study and learn about different types of music. I would scour the internet for hours researching new genres. I read countless articles and watched hours of interviews with musicians describing their creative process, inspiration, and work. I would stay up until 3am searching through LiveJournal music blogs and forums, watching YouTube clips, listening to Last.Fm, illegally downloading whole discographies or making mix CDs to listen to on the way to and from school. I prided myself for developing an “ear” for music. If I was hooked on a song, I extended my love by understanding the historical, geographical, social, political, and cultural contexts of its music genre or culture. I was voracious in my yearning to know the various lineages within Black music: the differences between Chicago Blues and Delta Blues, what hip hop shares with punk, how who we are and where we come from influence the distinction in sound.

In other words, I am a HUGE music nerd.

When I discovered the Center for Black Music Research (CBMR) while studying Jamaican dancehall music for a class project at Columbia College, I thought I died and went to heaven. I never dreamed a place like this could exist.

The CBMR, founded in 1983 by Dr. Samuel A. Floyd with his own personal collection, is a special collections archive meant to highlight the role Black music has played in the world. Later expanded in 1991 at Columbia College, the CBMR holds 47,000 sound recordings in all formats; over 100 individual archival collections over 15,000 scores, images, concert programs, and newspaper clippings; and 8,700 secondary resources, including books, dissertations, and serials. All the materials in the collection center the brilliance of African and Black musicians, music cultures, and histories originating from, or representing, the United States, Africa, Europe, Latin America, and the Caribbean. The CBMR was the only special collection like it at the time of its foundation. When I visited for the first time, I felt the magnitude of this fact.

From 2014 to 2016, the CBMR library became a sanctuary for me. The space itself was drab and not at all inviting, to be honest. But, the weight of knowledge that occupied its shelves drew me in. I learned so much during this time. How sacred it felt to exist within a space that expanded my understanding of not only Black music but also Blackness. I felt a sense of power and pride as I read about the African roots of Cúmbia music, the evolution of Jamaican reggae and dancehall in Puerto Rican reggaetón, and listened to the collaborations between bebop innovator Dizzy Gillespie and Afro-Cuban jazz musician Mario Bauzá. I was rediscovering Blackness. And, although these histories and cultures were different from my own, I felt welcomed and grounded by their Blackness. During my time at CBMR, I also learned that my obsession for music that began as an adolescent could become a career path in ethnomusicology if I chose. Before the age 23, I never heard that term or thought it possible to translate my love for music into the study of Black music cultures across the diaspora.

It wasn’t until I met Erin Glasco, one of my good friends, member of the Blackivists collective and badass, queer, radical archivist of my dreams, that I understood the importance of Black archives and the existence of community archives. Their passion illuminated the power archives have in shaping history as we know it — especially the history around Black, trans, and queer lives as well as social and political organizing work in the US. As I studied the history of Jamaican dancehall, Erin conducted research and curated a small exhibit at the CBMR on the FBI surveillance of noted singer, actor, and civil rights activist Paul Robeson.

Erin’s presence and the CBMR space challenged me to expand my idea of what roles Black folks could play in and outside of institutions like the archives and academia. Before 2014, I thought all archivists were old, white, history teachers who were fixated on the Founding Fathers. And, I believed all archives were basically just libraries. After 2016, however, I understood archives to be conduits of memory, spaces of curiosity, exploration, and infinite knowledge. Archives could exist beyond institutional spaces and be owned, created and cultivated by communities. I understood that while the archives were still predominantly white spaces, there were also Black archivists—like the Blackivists— who made it a priority to problematize, challenge, and reframe the role archival institutions play within communities. And, I learned that as a visual artist, I also have a stake in preserving Black historical archives.

Erin’s presence and the CBMR space challenged me to expand my idea of what roles Black folks could play in and outside of institutions like the archives and academia. Before 2014, I thought all archivists were old, white, history teachers who were fixated on the Founding Fathers. And, I believed all archives were basically just libraries. After 2016, however, I understood archives to be conduits of memory, spaces of curiosity, exploration, and infinite knowledge. Archives could exist beyond institutional spaces and be owned, created and cultivated by communities. I understood that while the archives were still predominantly white spaces, there were also Black archivists—like the Blackivists— who made it a priority to problematize, challenge, and reframe the role archival institutions play within communities. And, I learned that as a visual artist, I also have a stake in preserving Black historical archives.

While I knew CBMR to be a sacred space of memory, there seemed to be a disconnect between the Columbia College administration and the CBMR. Very few Columbia students, faculty, and staff knew of its existence. And, if they knew, I rarely saw them. Music scholars from places like the Netherlands, Germany, and other countries would come in during the summer. Their visits would activate the space. During the last three-to-four years, CBMR librarians Laura Lee Moses and Janet Harper, student assistants Dre X. Meza and Avia Bodemer, and research fellow Melanie Zeck, who I engaged with regularly, made efforts to bring folks in. However, their efforts were never sustained due to lack of funding and support from Columbia College administration.

When I visited the CBMR for the last time, Columbia’s previously subtle divestment from the archive became more apparent. I walked in the space and was greeted with empty bookshelves, tables and chairs pushed against walls, and a single baby-grand piano in the middle of the room. My stomach dropped when I saw the bare bookshelves. I shared my shock with Dre and they informed me that shifts were being made to how people could access CBMR’s library. The Columbia’s College Archives and Special Collections office moved all of the library books to the back room, making them no longer visible to visitors. So, instead of perusing at their leisure, visitors would have to look up a specific book online and then ask a librarian for access. The experience of discovering new knowledge that felt so intrinsic to accessing the library was lost.

In July 2019, the Columbia Chronicle reported that due to staffing challenges at the college, Laurie and Janet were terminated from the CBMR and Melanie resigned. With this news came confusion about what would happen to the collection. Will it remain its own designated space or will it become buried within Columbia’s larger library? How will the public or those outside academia access it?

“We will spend the coming year and beyond thinking through how we can best leverage this uniquely rich collection, and what resources will be required to highlight its value to our students and to scholars of the music of the African Diaspora,” said Kwang-Wu Kim, President and CEO of Columbia College in an email sent to faculty and staff. Currently, only researchers are allowed to schedule appointments with the main library to navigate the collection. Even so, it was unclear before the COVID-19 pandemic if the CBMR collections could be available to the public.

What was crystal clear to me upon hearing the news is that the public had no access to the very space that became something of a sanctuary for me during my undergraduate years. Like so many other institutions that hold hostage records of whole histories and people’s cultures, the CBMR became inaccessible to those outside its walls. While reading the article, hurt and anger lodged tightly in my throat; I began to dream.

In this dream, I obtained enough funding to recapture the CBMR collections from Columbia College library and relocate it to Washington Park—a central location on the South Side that is also the home to the DuSable Museum of African American History. I envisioned the CBMR expanding into a community space, a gallery space, and a performance space, while still grounded in its original identity as a “nexus for all who value Black music.” Here, in my reimagined CBMR, there are free classes teaching Black music cultures from around the globe; introducing ethnomusicology, archiving, and librarianship; and hosting workshops on how to start your own personal or community archive. This place is accessible to all. In this vision, the CBMR is reshaped with intention and care by Black archivists, artists, scholars, stakeholders and community members in Chicago. It is no longer a static space. Instead, it has truly become a conduit of memory, infinite possibility, and an incubator of innovation.

When I visited the CBMR for the last time, Columbia’s previously subtle divestment from the archive became more apparent. I walked in the space and was greeted with empty bookshelves, tables and chairs pushed against walls, and a single baby-grand piano in the middle of the room. My stomach dropped when I saw the bare bookshelves. I shared my shock with Dre and they informed me that shifts were being made to how people could access CBMR’s library. The Columbia’s College Archives and Special Collections office moved all of the library books to the back room, making them no longer visible to visitors. So, instead of perusing at their leisure, visitors would have to look up a specific book online and then ask a librarian for access. The experience of discovering new knowledge that felt so intrinsic to accessing the library was lost.

In July 2019, the Columbia Chronicle reported that due to staffing challenges at the college, Laurie and Janet were terminated from the CBMR and Melanie resigned. With this news came confusion about what would happen to the collection. Will it remain its own designated space or will it become buried within Columbia’s larger library? How will the public or those outside academia access it?

“We will spend the coming year and beyond thinking through how we can best leverage this uniquely rich collection, and what resources will be required to highlight its value to our students and to scholars of the music of the African Diaspora,” said Kwang-Wu Kim, President and CEO of Columbia College in an email sent to faculty and staff. Currently, only researchers are allowed to schedule appointments with the main library to navigate the collection. Even so, it was unclear before the COVID-19 pandemic if the CBMR collections could be available to the public.

What was crystal clear to me upon hearing the news is that the public had no access to the very space that became something of a sanctuary for me during my undergraduate years. Like so many other institutions that hold hostage records of whole histories and people’s cultures, the CBMR became inaccessible to those outside its walls. While reading the article, hurt and anger lodged tightly in my throat; I began to dream.

In this dream, I obtained enough funding to recapture the CBMR collections from Columbia College library and relocate it to Washington Park—a central location on the South Side that is also the home to the DuSable Museum of African American History. I envisioned the CBMR expanding into a community space, a gallery space, and a performance space, while still grounded in its original identity as a “nexus for all who value Black music.” Here, in my reimagined CBMR, there are free classes teaching Black music cultures from around the globe; introducing ethnomusicology, archiving, and librarianship; and hosting workshops on how to start your own personal or community archive. This place is accessible to all. In this vision, the CBMR is reshaped with intention and care by Black archivists, artists, scholars, stakeholders and community members in Chicago. It is no longer a static space. Instead, it has truly become a conduit of memory, infinite possibility, and an incubator of innovation.

I think back to my younger self. I wonder how different I would be if I had access to the CBMR, Reimagined. If I knew there was a space where I could listen to records of James Brown and Ella Fitzgerald? How different would my concept of Blues had been if I read, “Blues People: Negro Music in White America” by Leroi Jones as a senior in high school? What if I knew it was okay to nerd out on music and that it was possible for me to study ethnomusicology?

What if?

Although this dream is not a reality, I am left with the uncomfortable and unanswered question:

Who owns our story, our history, our culture?

Seems like it’s the highest bidder these days. Thousands upon thousands of photos, documents, books, music, and artifacts that tell stories of the lives, brilliance, and work of Black folks are behind walls, in closets, and on shelves, collecting dust. Accessible only to some, and inaccessible mostly to others. How do we recapture and reclaim them if we don’t know they exist? ︎

What if?

Although this dream is not a reality, I am left with the uncomfortable and unanswered question:

Who owns our story, our history, our culture?

Seems like it’s the highest bidder these days. Thousands upon thousands of photos, documents, books, music, and artifacts that tell stories of the lives, brilliance, and work of Black folks are behind walls, in closets, and on shelves, collecting dust. Accessible only to some, and inaccessible mostly to others. How do we recapture and reclaim them if we don’t know they exist? ︎

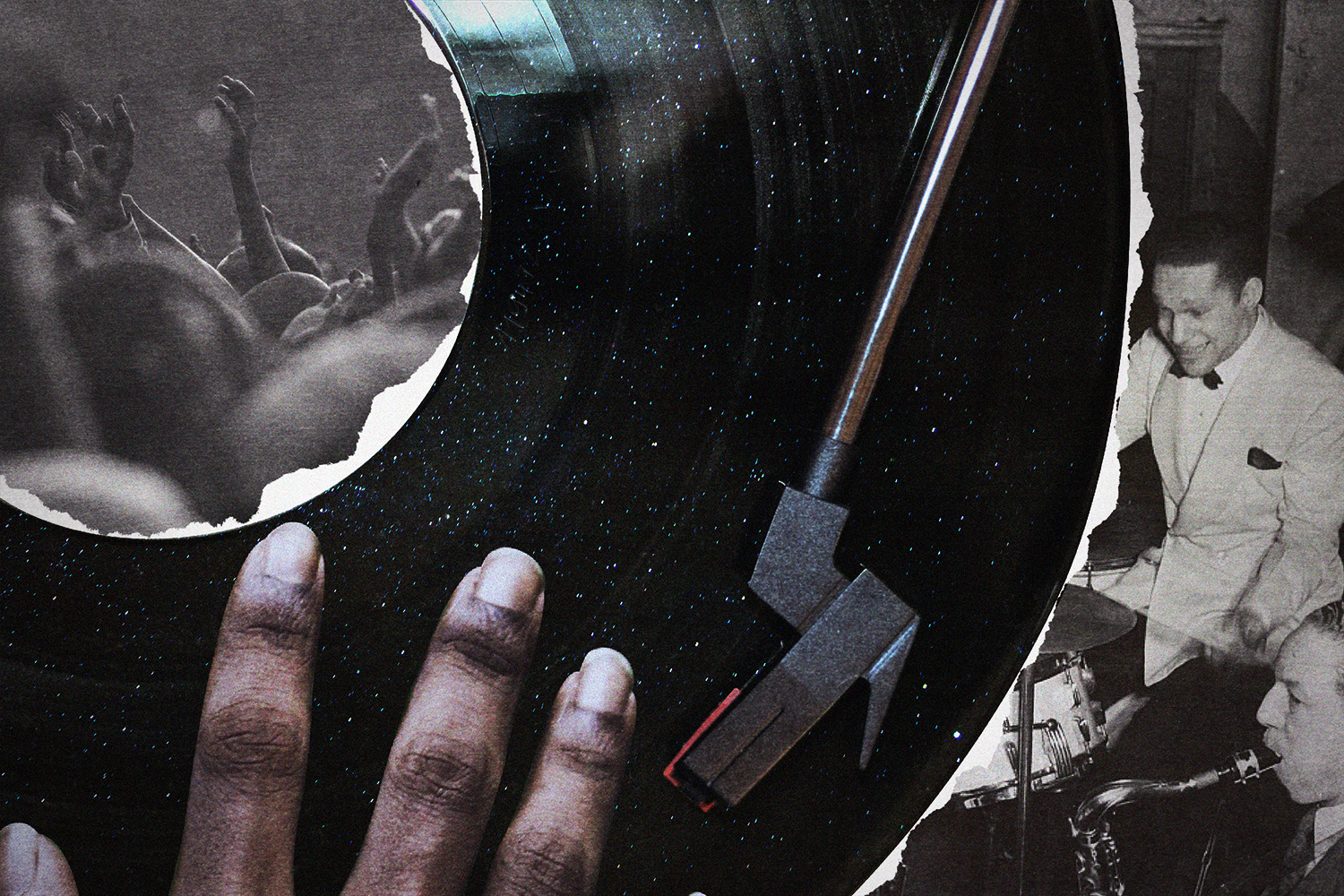

Ireashia M. Bennett (they/them) is a multidisciplinary artist and transmedia storyteller who explores the complexities of trauma, survival, and healing within Black communities. They earned a B.A. in Journalism from Columbia College Chicago. They produce multimedia essays, short documentaries, and experimental films to ensure complex issues are accessible to all. With multimedia collage, Ireashia weaves together archival materials with captured imagery to explore how trauma, and the process of healing through meaning-making, is embedded in Black people’s genealogy, ancestral memory, and history. Their artistic work has been exhibited locally in art spaces such as the Sullivan Galleries, Arts Incubator, Stony Island Arts Bank, and Chicago Art Department as well as nationally at the Museum of African American History in Boston, MA. They currently work as the Audio-Visual Production Manager at Ci3 at the University of Chicago, where they combine transmedia storytelling with adolescent sexual health research.