Love Through Loss: Activists Remember Each Life Taken in Violence

Interviews by Erin Glasco

I was asked to contribute a piece for this series that focused on my organizing experience with #NoCopAcademy (a youth-led grassroots campaign to stop the building of a $95 million police and fire training academy in Chicago) and the ways in which young organizers and activists capture the loss of Black life in their work, especially via corner memorials and other remembrances of Black lives lost. I thought it appropriate, rather than give my perspective, that I ask two of the young folks who were involved in #NoCop and who have both spent time organizing for Black liberation to illuminate theirs instead.

In this piece, I speak with Nita Tennyson (she/her) and Asha Edwards (she/her), who are both Black, queer, Chicago-based organizers who I had the pleasure to meet and work with during the #NoCop campaign. We speak on contending with the loss of Black lives and livelihoods, in general and during the coronavirus. We also discuss the ways, both personal and political, that they both have memorialized Black folks who have been lost or suffered grievous losses, be it at the hands of the state or through intercommunity violence.

These interviews have been edited for clarity and length.

In this piece, I speak with Nita Tennyson (she/her) and Asha Edwards (she/her), who are both Black, queer, Chicago-based organizers who I had the pleasure to meet and work with during the #NoCop campaign. We speak on contending with the loss of Black lives and livelihoods, in general and during the coronavirus. We also discuss the ways, both personal and political, that they both have memorialized Black folks who have been lost or suffered grievous losses, be it at the hands of the state or through intercommunity violence.

These interviews have been edited for clarity and length.

Interview with Nita Tennyson

Nita Tennyson is a former member of Assata’s Daughters, and was a youth organizer in the #NoCopAcademy campaign. Nita and I discussed corner memorials and remembrances of Black people who have lost their lives, as well the mutual aid she’s been able to offer through her organization, The Love Train. Nita also coordinated The Love Memorial—a march, candlelight vigil and lantern release held to honor all of the Black and Brown youth lost to violence this year.

Erin Glasco: Are you aware of any corner memorials or community remembrances for people who have been lost to state violence or people who have been, unfortunately, victims of intercommunity violence?

Nita Tennyson: I see memorials when I drive around. I know there’s one on 83rd [Street]. I know there’s one on 109th [Street]. Memorials are really not touched by people, so usually if they're there, they stay for a while until somebody comes and picks it up. And when people pass away, their family and the people who love them make their memorials, like that's how it is. I think that in Chicago, when people pass away, it's very important that they are remembered. So that's why people do candlelights and balloon releases and stuff like that.

EG: What do you think is the importance of corner memorials in Black communities?

NT: I think they are really important in Black communities because our youth, and people in general, who pass away from gun violence are not taken in a natural way, they are taken at the hands of something or someone else. I also know a girl who passed away this year, she got hit by a car. She didn't get shot. It’s important for people to be remembered, because when somebody passes away, it brings a lot of pain and it brings a lot of hurt. And even though people be like, “Pray for the family,” a lot of people create relationships with their friends, so their friends become family, too. And I think a lot of Chicago is hurt people that hurt people.

But really, these memorials help hurt people grieve, they help them remember that person because sometimes it's a memorial where the person was killed or where their house is. When it’s where they were killed, I feel like people do those types of memorials because they want to remember where their soul was. Because, you know, when someone passes away, their soul leaves their body at that time. So they want to remember them right there. They want to let go of balloons because they feel like that’s the last place they are. But some people do it at home because that's where they feel their spirit goes to, or their soul does. When I do balloon releases, sometimes I write a message on the balloon because, in theory, the balloon floats up, so why wouldn't it float to heaven?

Erin Glasco: Are you aware of any corner memorials or community remembrances for people who have been lost to state violence or people who have been, unfortunately, victims of intercommunity violence?

Nita Tennyson: I see memorials when I drive around. I know there’s one on 83rd [Street]. I know there’s one on 109th [Street]. Memorials are really not touched by people, so usually if they're there, they stay for a while until somebody comes and picks it up. And when people pass away, their family and the people who love them make their memorials, like that's how it is. I think that in Chicago, when people pass away, it's very important that they are remembered. So that's why people do candlelights and balloon releases and stuff like that.

EG: What do you think is the importance of corner memorials in Black communities?

NT: I think they are really important in Black communities because our youth, and people in general, who pass away from gun violence are not taken in a natural way, they are taken at the hands of something or someone else. I also know a girl who passed away this year, she got hit by a car. She didn't get shot. It’s important for people to be remembered, because when somebody passes away, it brings a lot of pain and it brings a lot of hurt. And even though people be like, “Pray for the family,” a lot of people create relationships with their friends, so their friends become family, too. And I think a lot of Chicago is hurt people that hurt people.

But really, these memorials help hurt people grieve, they help them remember that person because sometimes it's a memorial where the person was killed or where their house is. When it’s where they were killed, I feel like people do those types of memorials because they want to remember where their soul was. Because, you know, when someone passes away, their soul leaves their body at that time. So they want to remember them right there. They want to let go of balloons because they feel like that’s the last place they are. But some people do it at home because that's where they feel their spirit goes to, or their soul does. When I do balloon releases, sometimes I write a message on the balloon because, in theory, the balloon floats up, so why wouldn't it float to heaven?

EG: So, how do you remember folks you've lost personally? I know from following you on Twitter that you've suffered, unfortunately, a lot of loss. I’ve seen you mention on Twitter that the anniversary of the death of Michael Serrano, who was also a member of Assata’s Daughters and a organizer with #NoCop. Can you share the ways that you try to memorialize people that you’ve lost?

NT: When someone passes away, I usually try to make sure that I make it to the candlelight. When I go to candlelights, I bring balloons. I also bring candles and stuff and then for the funeral I have a friend who has a button maker and I like to make buttons because they are really important to people––you can always carry somebody with you wherever you go when you have a button. At the candlelights, everybody meets up and we let whoever wants to speak speak. Usually the mom speaks, usually somebody close to them speaks and then we let balloons go. I know a lot of people who have passed away that have stand-up boards for them, so you can take pictures with them on the board. For sure, I always get t-shirts with their faces or names on them because I like to wear them around when I go to the funeral, but that’s usually what we do. So, for the Love Memorial, this is something that is really different to me because it's personal, but it's also because this year I have also lost, I think, I have lost a friend every month this year—

EG: Oh my God.

NT: —except for August. Even in August, I knew somebody who passed away, we just weren’t close. It's really personal to me because since I've been doing the Love Train, I've been doing love all around Chicago, so it's important to me that Chicago knows that just because I'm giving out love doesn’t mean I don't feel y’alls pain, too. So, we can hurt together and grow together because I feel like once we love each other, we can heal, and once we heal each other, it can change. That’s my theory.

EG: I'm so sorry to hear that you’ve lost so many people this year. This year has been full of loss, so I'm so sorry, Nita. But what you're doing sounds amazing. Will you talk to me more about the Love Train? How did you come up with the idea? Who is involved? I want to know as much as you want to tell me about it.

NT: When someone passes away, I usually try to make sure that I make it to the candlelight. When I go to candlelights, I bring balloons. I also bring candles and stuff and then for the funeral I have a friend who has a button maker and I like to make buttons because they are really important to people––you can always carry somebody with you wherever you go when you have a button. At the candlelights, everybody meets up and we let whoever wants to speak speak. Usually the mom speaks, usually somebody close to them speaks and then we let balloons go. I know a lot of people who have passed away that have stand-up boards for them, so you can take pictures with them on the board. For sure, I always get t-shirts with their faces or names on them because I like to wear them around when I go to the funeral, but that’s usually what we do. So, for the Love Memorial, this is something that is really different to me because it's personal, but it's also because this year I have also lost, I think, I have lost a friend every month this year—

EG: Oh my God.

NT: —except for August. Even in August, I knew somebody who passed away, we just weren’t close. It's really personal to me because since I've been doing the Love Train, I've been doing love all around Chicago, so it's important to me that Chicago knows that just because I'm giving out love doesn’t mean I don't feel y’alls pain, too. So, we can hurt together and grow together because I feel like once we love each other, we can heal, and once we heal each other, it can change. That’s my theory.

EG: I'm so sorry to hear that you’ve lost so many people this year. This year has been full of loss, so I'm so sorry, Nita. But what you're doing sounds amazing. Will you talk to me more about the Love Train? How did you come up with the idea? Who is involved? I want to know as much as you want to tell me about it.

NT: The first day of the looting was May 31st. The second day, when it was really bad, that was the big day, that was June 1st. People usually get their LINK cards or their WIC and other benefits on the first of the month. And so when the looting happened it shut down basically all the resources in the community because either the stores were boarding up or getting stole from. Well, let me not say, “stole from”––people were getting what they needed. I saw on Facebook that people were making statuses like, “Y’all stole from WIC. My kids need milk.” It was a controversy on Facebook because people were saying things like, “Y’all should have milk left over for your kids in case of an emergency, so it's not anybody's fault.” But at the same time, in my mind, it's like: It's the first of the month. Most of their kids should be running out of milk because they're about to get more milk.

And so my friend has three kids and the daycare centers were closed. So I was watching her kids because everything was going crazy. It just so happened that I was buying a lot of stuff to have in the house for the kids and I ended up with extra supplies. I called my boyfriend's son’s mother and asked, “Do you want to go outside with me and pass out this extra stuff I have?” And it turned out they had some extra stuff, too, and we had six boxes of fruit and stuff from a food pantry. So, we washed off all the food and wrapped it up. And we went out on the corner with a basket of fruit and other foods, and a suitcase for diapers, wipes and formula. And people seen us and was like, “What are y’all doing?” We were like, “We're passing out free stuff. People are saying that because of the looting, there was no stuff that they could get. So, we want to make sure that everybody can get something, at least if they need it.” And so we went on live on Facebook, and it’s because so many people saw it and were sharing it that people were either coming to us to get stuff or coming to us to drop off extra stuff they had. We stood out there until curfew, and we left the basket with a lot of different stuff in it, and when we came back the next morning, everything was gone.

And so my friend has three kids and the daycare centers were closed. So I was watching her kids because everything was going crazy. It just so happened that I was buying a lot of stuff to have in the house for the kids and I ended up with extra supplies. I called my boyfriend's son’s mother and asked, “Do you want to go outside with me and pass out this extra stuff I have?” And it turned out they had some extra stuff, too, and we had six boxes of fruit and stuff from a food pantry. So, we washed off all the food and wrapped it up. And we went out on the corner with a basket of fruit and other foods, and a suitcase for diapers, wipes and formula. And people seen us and was like, “What are y’all doing?” We were like, “We're passing out free stuff. People are saying that because of the looting, there was no stuff that they could get. So, we want to make sure that everybody can get something, at least if they need it.” And so we went on live on Facebook, and it’s because so many people saw it and were sharing it that people were either coming to us to get stuff or coming to us to drop off extra stuff they had. We stood out there until curfew, and we left the basket with a lot of different stuff in it, and when we came back the next morning, everything was gone.

![Image: A color photo with views of businesses during the West Side riots after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., Chicago, IL, April 1968. Photographed in the vicinity of Marillac House, a community center at 2822 West Jackson Boulevard. West Side Riots Chicago Photograph Collection [ICHi-040026], Chicago History Museum. Photographer: Sister Julia of Marillac House.](https://freight.cargo.site/t/original/i/5bdf70bb3a62ec6ec4b50ea21cb32d426a7f66d79ddd9717f1198ea6a22b0f8d/i040026_pm.jpg)

EG: Wow. So how often have you done the Love Train?

NT: In total, this whole summer, I believe I went out thirty-eight times.

EG: Oh, my goodness. Thirty-eight times is a lot! How often were you going out?

NT: I might have gone out more than that, actually. I do know I went to, at least, twenty-five different communities because for the first four weeks, I was going out four times a week. And then the next two and a half weeks, I was going out three times a week. Now, I go out two times a week. Or sometimes once because I try to spread it out every time I go. I've been to Englewood, Auburn Gresham, Chatham, Austin, West Garfield Park, Washington Park, Near West Side, and South Shore. I’ve been everywhere.

EG: Can you tell me about the Love Memorial?

NT: It started because my best friend's memorial day came up. She passed away two years ago, and so I did a day for her: it was Jessie Day. So then I was like, “Hmm, I should start doing this for other people.” So, now I dedicate the Love Train to people as we go out, and so the last stop we went to was for a friend of mine, really a brother, Akil. His son passed away before his first birthday this year. This is directly tied into #DefundCPD because he was denied health insurance and he had a heart condition. He survived three heart surgeries, beat COVID-19, but passed away from a heart attack. They made a GoFundMe so he could get the surgery he actually needed, but he passed away before anybody could even fill that up. People shouldn't have to fight so hard for medical insurance. Like, he was born here. Why doesn't he already have it? You know? So, with the Love Train, we go out and pass out stuff.

Now, the Love Memorial is dedicated to Michael (Serrano) because he was killed in intercommunity violence last year. September 13th. It’s going to be a whole year he’s been gone, a whole year, and also his first birthday without him, too. So I wanted to do something for him. At first I was just going to pass stuff out in his name. But I feel like there's been a lot of loss this year for everybody. We lost Kobe, we lost Black Panther, we lost so many people, and then COVID. So many people from my school have passed away from COVID. I've been to funerals this year for people I never thought in a million years I would have to be at the funeral for--especially not this year, and especially not from COVID, it's just wild. So, I feel like the city is going through so much pain right now. And the memorial to remember all the Black and Brown youth who were lost this year will be something that will help people remember their people. We are going to do a candle lighting; I'm gonna say their names. It’s going to be a very sentimental event. At the end, I'm going to let people speak, and then we're going to let the lanterns go. I have been doing research, trying to make sure I'm all-inclusive, so I've been inviting families and asking permission to honor their children.

NT: In total, this whole summer, I believe I went out thirty-eight times.

EG: Oh, my goodness. Thirty-eight times is a lot! How often were you going out?

NT: I might have gone out more than that, actually. I do know I went to, at least, twenty-five different communities because for the first four weeks, I was going out four times a week. And then the next two and a half weeks, I was going out three times a week. Now, I go out two times a week. Or sometimes once because I try to spread it out every time I go. I've been to Englewood, Auburn Gresham, Chatham, Austin, West Garfield Park, Washington Park, Near West Side, and South Shore. I’ve been everywhere.

EG: Can you tell me about the Love Memorial?

NT: It started because my best friend's memorial day came up. She passed away two years ago, and so I did a day for her: it was Jessie Day. So then I was like, “Hmm, I should start doing this for other people.” So, now I dedicate the Love Train to people as we go out, and so the last stop we went to was for a friend of mine, really a brother, Akil. His son passed away before his first birthday this year. This is directly tied into #DefundCPD because he was denied health insurance and he had a heart condition. He survived three heart surgeries, beat COVID-19, but passed away from a heart attack. They made a GoFundMe so he could get the surgery he actually needed, but he passed away before anybody could even fill that up. People shouldn't have to fight so hard for medical insurance. Like, he was born here. Why doesn't he already have it? You know? So, with the Love Train, we go out and pass out stuff.

Now, the Love Memorial is dedicated to Michael (Serrano) because he was killed in intercommunity violence last year. September 13th. It’s going to be a whole year he’s been gone, a whole year, and also his first birthday without him, too. So I wanted to do something for him. At first I was just going to pass stuff out in his name. But I feel like there's been a lot of loss this year for everybody. We lost Kobe, we lost Black Panther, we lost so many people, and then COVID. So many people from my school have passed away from COVID. I've been to funerals this year for people I never thought in a million years I would have to be at the funeral for--especially not this year, and especially not from COVID, it's just wild. So, I feel like the city is going through so much pain right now. And the memorial to remember all the Black and Brown youth who were lost this year will be something that will help people remember their people. We are going to do a candle lighting; I'm gonna say their names. It’s going to be a very sentimental event. At the end, I'm going to let people speak, and then we're going to let the lanterns go. I have been doing research, trying to make sure I'm all-inclusive, so I've been inviting families and asking permission to honor their children.

EG: When do you plan on holding the Love Memorial?

NT: 9/11, because I feel that that’s a date we should reclaim. The state of emergency is our youth are dying off and they should not be because we should have resources that prevent these things from happening. We should have resources to heal those people that are hurt, we should have mental health facilities, we should have trauma counseling, we should have places for kids to do art when they're going through stuff. We should have all those things, and I feel like everything is connected, so that's why I'm doing it.

EG: That’s amazing, Nita. I’m so impressed with the thought you’ve put into honoring folks that we’ve lost too soon. And I really appreciate all that you and the folks that you're working with are doing to make this a reality. Is there anything else that you just want folks to know in general about the Love Train or the Love Memorial, or anything else that we talked about today?

NT: I just want folks to realize that even though everything looks really hard right now, we are gonna make it. We just got to come together, which we are doing because it's been hella mutual aid everywhere. It's been so beautiful. It's been youth organizers taking over everything this summer. So I just want people to realize there's a lot of pain, and it's a lot of loss, but we are going to get through. ︎

NT: 9/11, because I feel that that’s a date we should reclaim. The state of emergency is our youth are dying off and they should not be because we should have resources that prevent these things from happening. We should have resources to heal those people that are hurt, we should have mental health facilities, we should have trauma counseling, we should have places for kids to do art when they're going through stuff. We should have all those things, and I feel like everything is connected, so that's why I'm doing it.

EG: That’s amazing, Nita. I’m so impressed with the thought you’ve put into honoring folks that we’ve lost too soon. And I really appreciate all that you and the folks that you're working with are doing to make this a reality. Is there anything else that you just want folks to know in general about the Love Train or the Love Memorial, or anything else that we talked about today?

NT: I just want folks to realize that even though everything looks really hard right now, we are gonna make it. We just got to come together, which we are doing because it's been hella mutual aid everywhere. It's been so beautiful. It's been youth organizers taking over everything this summer. So I just want people to realize there's a lot of pain, and it's a lot of loss, but we are going to get through. ︎

Interview with Asha Edwards

Asha Edwards is a student at UIC who has been participating in organizing work since she was in high school. She is a member of Assata’s Daughters and Dissenters, and organized with the #NoCopAcademy campaign. We discuss how Asha got her start in organizing, her work this summer with #CopsOutCPS, and how the loss of Black people and futures are memorialized in her organizing work.

Erin Glasco: Can you share how you got involved with the campaign? And how in general you got involved with organizing and activism?

Asha Edwards: I was a sophomore in high school, I joined a grassroots organization called Assata’s Daughters, which teaches about the Black radical tradition, and Black feminist theory. We engaged in direct action, community building, and mutual aid, and how we get free for Black liberation. I had been in Assata’s for a little over a year, and then, I remember, the adult organizers invited some of our youth to a meeting about #NoCop, and we just kind of kept going.

EG: Can you talk about how you saw your role in #NoCop?

AE: Well, one thing I appreciated about the campaign is that the adult organizers and mentors wanted everyone's input to see what works for us and what roles we actually wanted to engage in. I was kind of a part of the art team and, like, it wasn't really a team, in a way, it was just a lot of voluntary work, but it was still organized. It was mutual in a sense.

EG: Were you able to be involved with the different actions that went on throughout the campaign? I know there were a lot of them, but were there any that were particularly memorable for you?

AE: Oh, yes. One of my favorite parts of the campaign was actually helping to organize the direct actions we did. There were actions that were my favorite, but there were also ones that shook me up in a way that I never felt before.

EG: I would love to hear about those experiences, the ones you felt that shook you to your core.

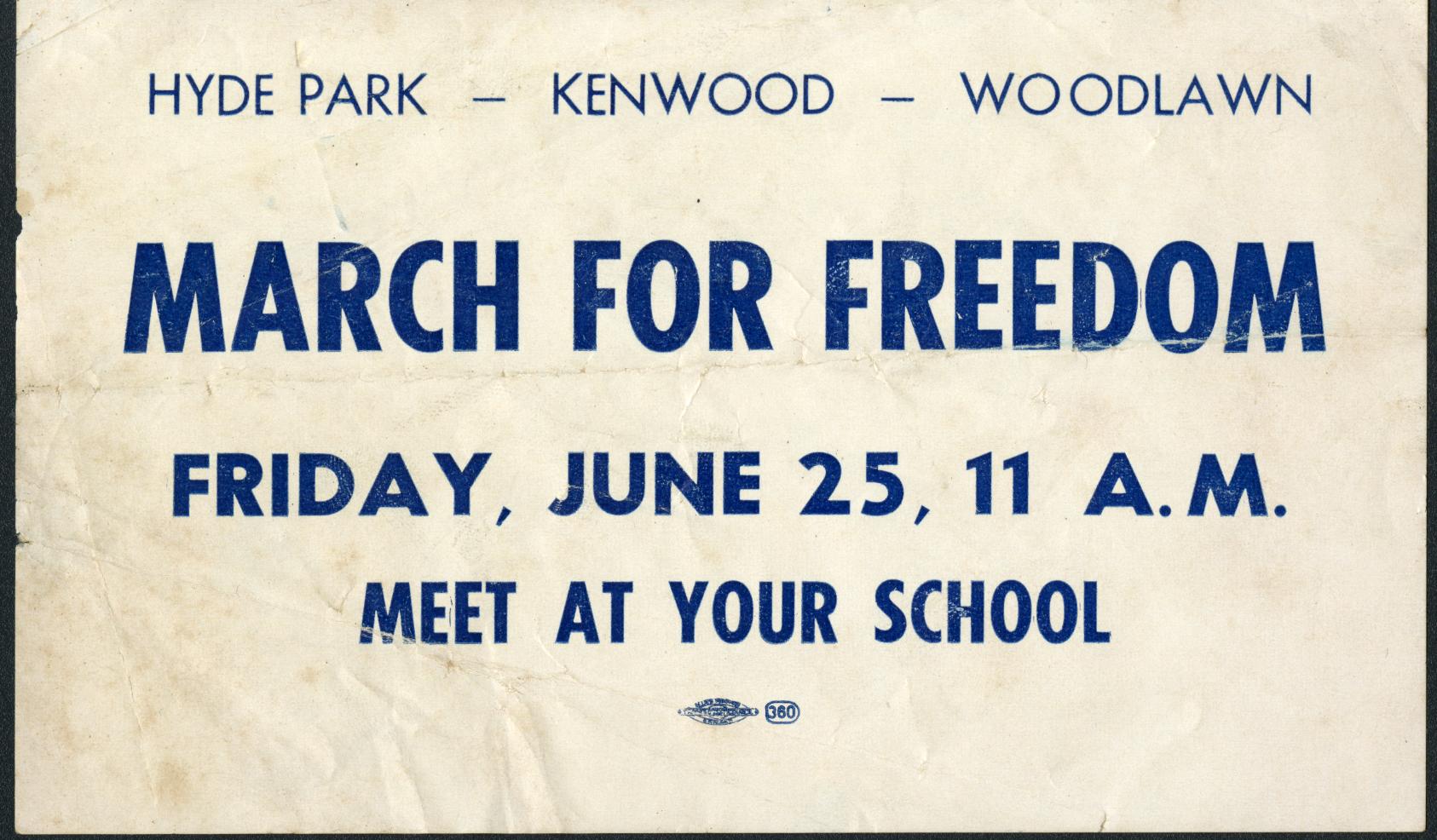

AE: Now, I’m thinking of even more events. [laughs] Because there were multiple events at the same location, City Hall, and they were all very distinct in a way. I really loved the one where we created the art installations of a graveyard. And I'd never seen that before in my life, because I didn't really know much about organizing or the history of how people changed the narrative. So I thought that was very powerful, just seeing how the city has continuously divested from essential community resources. However, the Chicago Police Department (CPD) budget has increased every year since 1968, I believe. So, to see the effects of that visually, like you guys are allowing this to die because you refuse to invest in what actually keeps us safe and what the community believes can keep us safe. And it was very powerful, especially when we laid on the ground as a die-in. That was my first die-in, and it felt very soulful, especially with the singing. I remember Page [May, founder of Assata’s Daughters] started a song, and it was very beautiful and sad, in a way. It was sad because there were police officers and white people just laughing at us. But, I still felt very empowered because at the same time there were, of course, white allies who kept a circle around us. There were my friends. There were other Assata’s peers, there were people blocking elevators, just holding it down. And in spite of it all, I felt very safe and supported and loved.

EG: That is lovely. It's interesting that you bring up that action because that's one that was really memorable for me too. Seeing the tombstones in City Hall was just powerful. Can you tell me why the decision was made in particular to use tombstones in that action?

Erin Glasco: Can you share how you got involved with the campaign? And how in general you got involved with organizing and activism?

Asha Edwards: I was a sophomore in high school, I joined a grassroots organization called Assata’s Daughters, which teaches about the Black radical tradition, and Black feminist theory. We engaged in direct action, community building, and mutual aid, and how we get free for Black liberation. I had been in Assata’s for a little over a year, and then, I remember, the adult organizers invited some of our youth to a meeting about #NoCop, and we just kind of kept going.

EG: Can you talk about how you saw your role in #NoCop?

AE: Well, one thing I appreciated about the campaign is that the adult organizers and mentors wanted everyone's input to see what works for us and what roles we actually wanted to engage in. I was kind of a part of the art team and, like, it wasn't really a team, in a way, it was just a lot of voluntary work, but it was still organized. It was mutual in a sense.

EG: Were you able to be involved with the different actions that went on throughout the campaign? I know there were a lot of them, but were there any that were particularly memorable for you?

AE: Oh, yes. One of my favorite parts of the campaign was actually helping to organize the direct actions we did. There were actions that were my favorite, but there were also ones that shook me up in a way that I never felt before.

EG: I would love to hear about those experiences, the ones you felt that shook you to your core.

AE: Now, I’m thinking of even more events. [laughs] Because there were multiple events at the same location, City Hall, and they were all very distinct in a way. I really loved the one where we created the art installations of a graveyard. And I'd never seen that before in my life, because I didn't really know much about organizing or the history of how people changed the narrative. So I thought that was very powerful, just seeing how the city has continuously divested from essential community resources. However, the Chicago Police Department (CPD) budget has increased every year since 1968, I believe. So, to see the effects of that visually, like you guys are allowing this to die because you refuse to invest in what actually keeps us safe and what the community believes can keep us safe. And it was very powerful, especially when we laid on the ground as a die-in. That was my first die-in, and it felt very soulful, especially with the singing. I remember Page [May, founder of Assata’s Daughters] started a song, and it was very beautiful and sad, in a way. It was sad because there were police officers and white people just laughing at us. But, I still felt very empowered because at the same time there were, of course, white allies who kept a circle around us. There were my friends. There were other Assata’s peers, there were people blocking elevators, just holding it down. And in spite of it all, I felt very safe and supported and loved.

EG: That is lovely. It's interesting that you bring up that action because that's one that was really memorable for me too. Seeing the tombstones in City Hall was just powerful. Can you tell me why the decision was made in particular to use tombstones in that action?

AE: The tombstones signified how we let these essential community resources die, and thus, our people essentially die because they're not looked at as being worthy of having what we need. They discard Black life. They see us as not worthy, so they neglect our needs, essentially. And I felt like the tombstones really grasped that. I remember it showed a lot of Black youth who were killed by the police. The tombstones showed, I think, all of the 50 schools that closed down and how they were majority Black and Brown schools and the chaos that that caused. And we did the die-in to represent: “This is what you guys are actually doing. This does not help us and you are destroying Black lives for your own political gain or to keep the status quo that is inherently anti-Black and violent. That's not acceptable. You are accepting our deaths, in a way.”

EG: Yeah, that was really powerful. Thank you so much for sharing that because it was a really powerful memorial, of a type, to the myriad losses we see in Black communities. The people that were lost, the community sustaining services that were lost. Thank you so much for that work.

AE: It was all just a very lovely experience. And that's how I made a lot of relationships today in who I organize with and how our networks all intertwined with each other. Now, I see, we could do this together, and then we could join in solidarity with this event.

EG: What have you been involved with in terms of organizing since #NoCop ended?

AE: Campaign-wise, I’ve been involved with the #CopsOutCPS campaign. I've attended a lot of direct actions.

EG: I know with the #CopsOutCPS campaign, there have been a lot of direct actions of various kinds, including some teach-ins held in the front of CPS School Board members’ homes to try to get CPS to end their relationship with CPD. Can you tell me more about the campaign?

EG: Yeah, that was really powerful. Thank you so much for sharing that because it was a really powerful memorial, of a type, to the myriad losses we see in Black communities. The people that were lost, the community sustaining services that were lost. Thank you so much for that work.

AE: It was all just a very lovely experience. And that's how I made a lot of relationships today in who I organize with and how our networks all intertwined with each other. Now, I see, we could do this together, and then we could join in solidarity with this event.

EG: What have you been involved with in terms of organizing since #NoCop ended?

AE: Campaign-wise, I’ve been involved with the #CopsOutCPS campaign. I've attended a lot of direct actions.

EG: I know with the #CopsOutCPS campaign, there have been a lot of direct actions of various kinds, including some teach-ins held in the front of CPS School Board members’ homes to try to get CPS to end their relationship with CPD. Can you tell me more about the campaign?

AE: I remember at first we called it, “Police Free Schools.” And I remember initially that Brighton Park Neighborhood Council (BPNC) were the ones, along with some other organizations, who really got this campaign off the ground years ago. Several youth members of BPNC, and other people at their schools, really helped to set the foundation for what led to this shift in the narrative change that cops do not belong in schools. During the uprisings, this message seriously got amplified because more people saw how violent the police are. There was a public shift in the narrative that cops no longer belong in our schools and that they don't keep us safe. And we kind of shifted the narrative of what can actually create a safe space in a school environment. And that's when the $33 million contract between CPS and the police became more popularized, and people got really angry about that. So, during the summer it was a really charged time—in a good way, because now people are learning more about why we want to get cops out of schools. But also they wanted to take action. So, this summer really sparked the campaign. We had a lot of meetings. [laughs] Some of which were with high school students who are just learning about the history of policing or cops in schools, and how that was not extremely effective. And we were concerned with actually building with them. We asked, “Then what do you need to keep yourself supported, loved, and safe in your school?” And then the two months before the vote, that was when things really got intense and busy. There was a lot of cool arts work, there were a lot of great events. And I remember during the first vote in late June, we went to Miguel’s [del Valle] house. He's the President of the Board of Education. And we just let him know, “Hey, what you're doing is anti-Black and here are students coming to tell you that they don't want cops in their schools. And if you ignore them, then you're ignoring Black and Brown youth and we’re going to use that against you.”

So after that event, people were like, “What? I want to get into this because oh, no, no way we could do something else about it? Oh, I want to be a part of that.” So, then a lot more youth wanted to get more involved. And then we learned about local school councils, and how we said it should not be up to your local school councils because not all of them have the power, most are adultist, most do not actually represent the student body. So, that led to a lot of events throughout the summer. A lot of our youth talked to the Board of Education members and also aldermen and local school councils, even though that wasn't our goal. We wanted to, at least, try and build momentum, and tell our schools that, “Hey, these students do not want cops in our school.” So some people created a survey, and they got hundreds of responses and then people at my school had a march—

EG: What school are you talking about?

AE: I graduated from Whitney Young High School on the Near West Side. And we had a march and rally at Whitney Young, and so many people came out. Class is not in session and we had a great turnout.

EG: So, what was the outcome? I know several school councils voted over the summer on whether or not to keep cops in school.

AE: They ultimately voted to retain. It was very insulting, and the media portrayed how the administration basically ignored youth, and went with their adultist, dismissive ways. We were also exposing the administration because they’d had a long history of being essentially violent and dismissing what actually happens in our schools. They also ignored our data, we provided alternatives and ideas and feedback from students who said they didn’t want cops in our schools. Even though they voted to retain, they said, ultimately, that they will try to get cops out of our school and said that the vote can be revisited during the school year. I still consider it a win because we had a decent amount of people who came to the student’s side. There were teachers who came to our rally and our march and they tried to talk to other teachers, and it really started a very important conversation about what goes on in that toxic high school.

So after that event, people were like, “What? I want to get into this because oh, no, no way we could do something else about it? Oh, I want to be a part of that.” So, then a lot more youth wanted to get more involved. And then we learned about local school councils, and how we said it should not be up to your local school councils because not all of them have the power, most are adultist, most do not actually represent the student body. So, that led to a lot of events throughout the summer. A lot of our youth talked to the Board of Education members and also aldermen and local school councils, even though that wasn't our goal. We wanted to, at least, try and build momentum, and tell our schools that, “Hey, these students do not want cops in our school.” So some people created a survey, and they got hundreds of responses and then people at my school had a march—

EG: What school are you talking about?

AE: I graduated from Whitney Young High School on the Near West Side. And we had a march and rally at Whitney Young, and so many people came out. Class is not in session and we had a great turnout.

EG: So, what was the outcome? I know several school councils voted over the summer on whether or not to keep cops in school.

AE: They ultimately voted to retain. It was very insulting, and the media portrayed how the administration basically ignored youth, and went with their adultist, dismissive ways. We were also exposing the administration because they’d had a long history of being essentially violent and dismissing what actually happens in our schools. They also ignored our data, we provided alternatives and ideas and feedback from students who said they didn’t want cops in our schools. Even though they voted to retain, they said, ultimately, that they will try to get cops out of our school and said that the vote can be revisited during the school year. I still consider it a win because we had a decent amount of people who came to the student’s side. There were teachers who came to our rally and our march and they tried to talk to other teachers, and it really started a very important conversation about what goes on in that toxic high school.

EG: Wonderful. That's a big deal. That's a win, right? We know, in the organizing world, getting people to move a vote is certainly enough to be considered a win. And I really enjoyed seeing so many righteous, fierce and loaded with information young people out this summer really pushing adults to do better. I noticed during the final vote on #CopsOutCPS that there was a canvas poster at the action that was titled “We do this for,” with people's names written on it. One of the things I’m interested in is talking about makeshift or corner memorials that memorialize people that have been lost, and the ways in which we memorialize people in movement work. So, like with the tombstones that happened during #NoCop action, can you talk about why it was important to have that remembrance at the action?

AE: I really loved that banner, and I’m so glad it was there because it shows that we are out here, not just for ourselves, but for our people. And in my opinion, it's insulting how people—especially the media—try to twist our story in a way and think we're just idiots or rambunctious, and they think we're not human, in a sense. And they easily dismiss these people and their lives, and what they’ve done. So when we write her name, when we write his name, when we write their name, I feel like we're not forgetting their stories and we’re remembering them along this long-time fight, in a sense. I really love that when we memorialize our people, then we honor them and make sure their names are never forgotten because, in the end, they were not martyrs. They did not want to die. These people are gone, but they wanted to live their lives. So, we want to make sure that their lives are still remembered and still appreciated. We give love and lights to them through these memorials. We want to build a better future where they won’t have to die or where there's no suffering so we can build towards the future that actually lets us live and thrive. And not just survive but actually thrive in a sense, where we are all supported. A future where we don't have to struggle and we're liberated.

EG: You answered this more generally, but I’m curious to know why you think it’s important in particular for Black folks to uplift the names of folks who have been murdered or victims of various kinds of state violence? Do you think these kinds of memorials have a different kind of resonance in Black communities?

AE: In particular to Black people, I think two things: First, I really despise how there is a very powerful narrative that Black people don’t care about themselves, in a sense. The media will say, “Well, y’all don't do this when your people are victims of Black-on-Black crime.” Even though that’s a myth. It was very hurtful, and it enrages me how people get to that conclusion that we do not care about our people. But the media will never amplify these people who lost their lives. They will just say, “A man, 32, dead.” Or they’ll say the police responded, but won’t talk about how the police didn’t do anything to actually help them. So, I feel Black people, we have the power to tell our own stories, we have the power to amplify their lives. Second, we have the power to actually create a community-led response to what's going on. And I feel like if it’s not Black people, no one else will do it because the world is anti-Black. So, through our love, through our connections, it is our duty to uplift these people. It is our duty to recognize these were people and now they’re gone. It is our duty to never forget them. They are not disposable. ︎

AE: I really loved that banner, and I’m so glad it was there because it shows that we are out here, not just for ourselves, but for our people. And in my opinion, it's insulting how people—especially the media—try to twist our story in a way and think we're just idiots or rambunctious, and they think we're not human, in a sense. And they easily dismiss these people and their lives, and what they’ve done. So when we write her name, when we write his name, when we write their name, I feel like we're not forgetting their stories and we’re remembering them along this long-time fight, in a sense. I really love that when we memorialize our people, then we honor them and make sure their names are never forgotten because, in the end, they were not martyrs. They did not want to die. These people are gone, but they wanted to live their lives. So, we want to make sure that their lives are still remembered and still appreciated. We give love and lights to them through these memorials. We want to build a better future where they won’t have to die or where there's no suffering so we can build towards the future that actually lets us live and thrive. And not just survive but actually thrive in a sense, where we are all supported. A future where we don't have to struggle and we're liberated.

EG: You answered this more generally, but I’m curious to know why you think it’s important in particular for Black folks to uplift the names of folks who have been murdered or victims of various kinds of state violence? Do you think these kinds of memorials have a different kind of resonance in Black communities?

AE: In particular to Black people, I think two things: First, I really despise how there is a very powerful narrative that Black people don’t care about themselves, in a sense. The media will say, “Well, y’all don't do this when your people are victims of Black-on-Black crime.” Even though that’s a myth. It was very hurtful, and it enrages me how people get to that conclusion that we do not care about our people. But the media will never amplify these people who lost their lives. They will just say, “A man, 32, dead.” Or they’ll say the police responded, but won’t talk about how the police didn’t do anything to actually help them. So, I feel Black people, we have the power to tell our own stories, we have the power to amplify their lives. Second, we have the power to actually create a community-led response to what's going on. And I feel like if it’s not Black people, no one else will do it because the world is anti-Black. So, through our love, through our connections, it is our duty to uplift these people. It is our duty to recognize these were people and now they’re gone. It is our duty to never forget them. They are not disposable. ︎

Erin Glasco (they/she) is a Black, queer, nonbinary femme who works as an independent archivist and researcher. Erin holds a MS in Library and Information Science from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Erin served as the Research Team Lead for #NoCopAcademy campaign. They are a member of The Blackivists, a collective of Black archivists who prioritize Black cultural heritage preservation and memory work. Erin’s interests include preserving and uplifting Black LGBTQIA+ narratives and materials, using transformative justice to inform community archival practice, and lending support to Black, queer, feminist informed grassroots movement work.