How to Make a Museum: Christina Shutt Talks Operations and Action in Black Museums

Interview by Stacie Williams and Steven D. Booth

Christina Shutt (she, her) currently serves as the Executive Director for the Mosaic Templars Cultural Center, the African American museum of history and culture for the state of Arkansas. Christina earned a Bachelor’s Degree in History from Central Methodist University, and holds two Masters’ degrees in Archival Management and History, with an emphasis on collective memory and public representations from Simmons University. Under Christina’s leadership, the museum has seen significant increases in visitor audience, fundraising, and exhibition development with her co-curated exhibit, “Don’t Touch My Crown,” winning the 2019 Arkansas Museums Association Award for Outstanding Exhibition. Additionally, Christina’s innovative and collaborative leadership resulted in the Mosaic Templars Cultural Center being awarded first-time national museum accreditation, making it only the ninth black culture museum in the United States to receive this designation.

This interview has been condensed for length and edited for clarity.

Steven D. Booth: Can you tell us about the history of the Mosaic Templars?

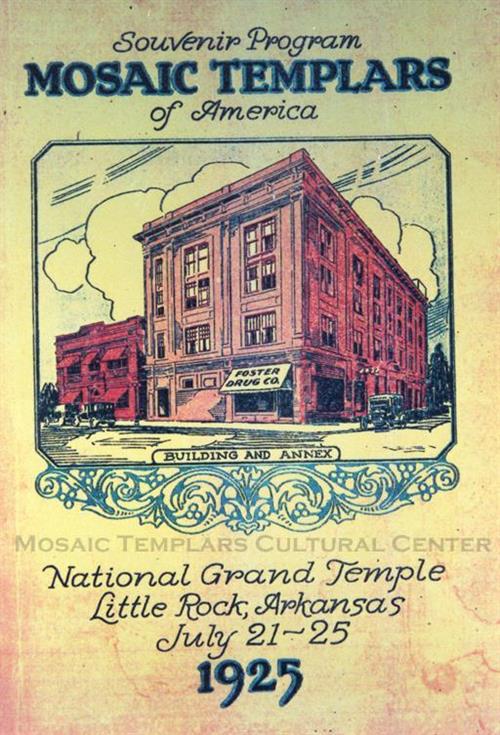

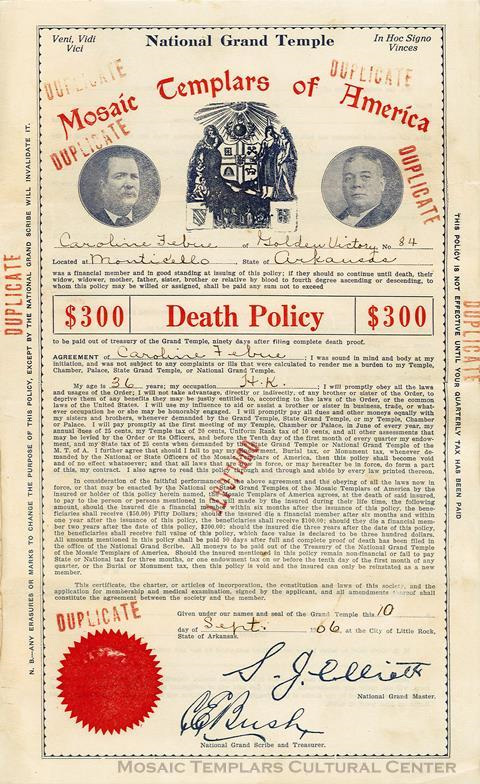

Christina Shutt: The organization we’re named in honor of is the Mosaic Templars of America, a Black fraternal organization started in 1882 and incorporated in 1883. They were an international burial organization with chapters in 26 states and six countries. The story is that an older woman walks up to John Bush and Chester Keatts on the street and asks for money to bury her husband. There had been an insurance report that said African Americans were not worth burying, and, as a result, they couldn’t get life insurance. Bush and Keatts realized this business opportunity and started offering insurance policies. As the community grew and expanded, so did their business. They built the international headquarters, the state office building next door, as well as a third building that served as a segregated hospital and nurses’ training center. During the Great Depression, the organization fell into receivership and bankruptcy, and the building mostly sat vacant for years. In the 1990s, the community found out the building was going to be bulldozed and replaced with a fast-food chain. So they started lobbying the legislature and, eventually, in 2001, they successfully established the Mosaic Templars Center for American American Culture and Business Enterprise, a state museum.

In 2005, repairs on the building began to remodel the original structure that was built in 1913 and dedicated by Booker T. Washington. A homeless man wandered in, lit a fire to warm himself, and the building caught on fire and burned down. So the group decided to rebuild on the same footprint based on the original building. The crown molding, the tintype ceiling, even the creaks in the wooden floor were all designed to mimic the original structure. Most residents who visit think it’s the original structure, and not a new building, which opened in 2008.

Stacie Williams: What does it mean for you to be heading this Black collection within the community, in Arkansas, in Little Rock, with the legacy of Little Rock and desegregation?

This interview has been condensed for length and edited for clarity.

Steven D. Booth: Can you tell us about the history of the Mosaic Templars?

Christina Shutt: The organization we’re named in honor of is the Mosaic Templars of America, a Black fraternal organization started in 1882 and incorporated in 1883. They were an international burial organization with chapters in 26 states and six countries. The story is that an older woman walks up to John Bush and Chester Keatts on the street and asks for money to bury her husband. There had been an insurance report that said African Americans were not worth burying, and, as a result, they couldn’t get life insurance. Bush and Keatts realized this business opportunity and started offering insurance policies. As the community grew and expanded, so did their business. They built the international headquarters, the state office building next door, as well as a third building that served as a segregated hospital and nurses’ training center. During the Great Depression, the organization fell into receivership and bankruptcy, and the building mostly sat vacant for years. In the 1990s, the community found out the building was going to be bulldozed and replaced with a fast-food chain. So they started lobbying the legislature and, eventually, in 2001, they successfully established the Mosaic Templars Center for American American Culture and Business Enterprise, a state museum.

In 2005, repairs on the building began to remodel the original structure that was built in 1913 and dedicated by Booker T. Washington. A homeless man wandered in, lit a fire to warm himself, and the building caught on fire and burned down. So the group decided to rebuild on the same footprint based on the original building. The crown molding, the tintype ceiling, even the creaks in the wooden floor were all designed to mimic the original structure. Most residents who visit think it’s the original structure, and not a new building, which opened in 2008.

Stacie Williams: What does it mean for you to be heading this Black collection within the community, in Arkansas, in Little Rock, with the legacy of Little Rock and desegregation?

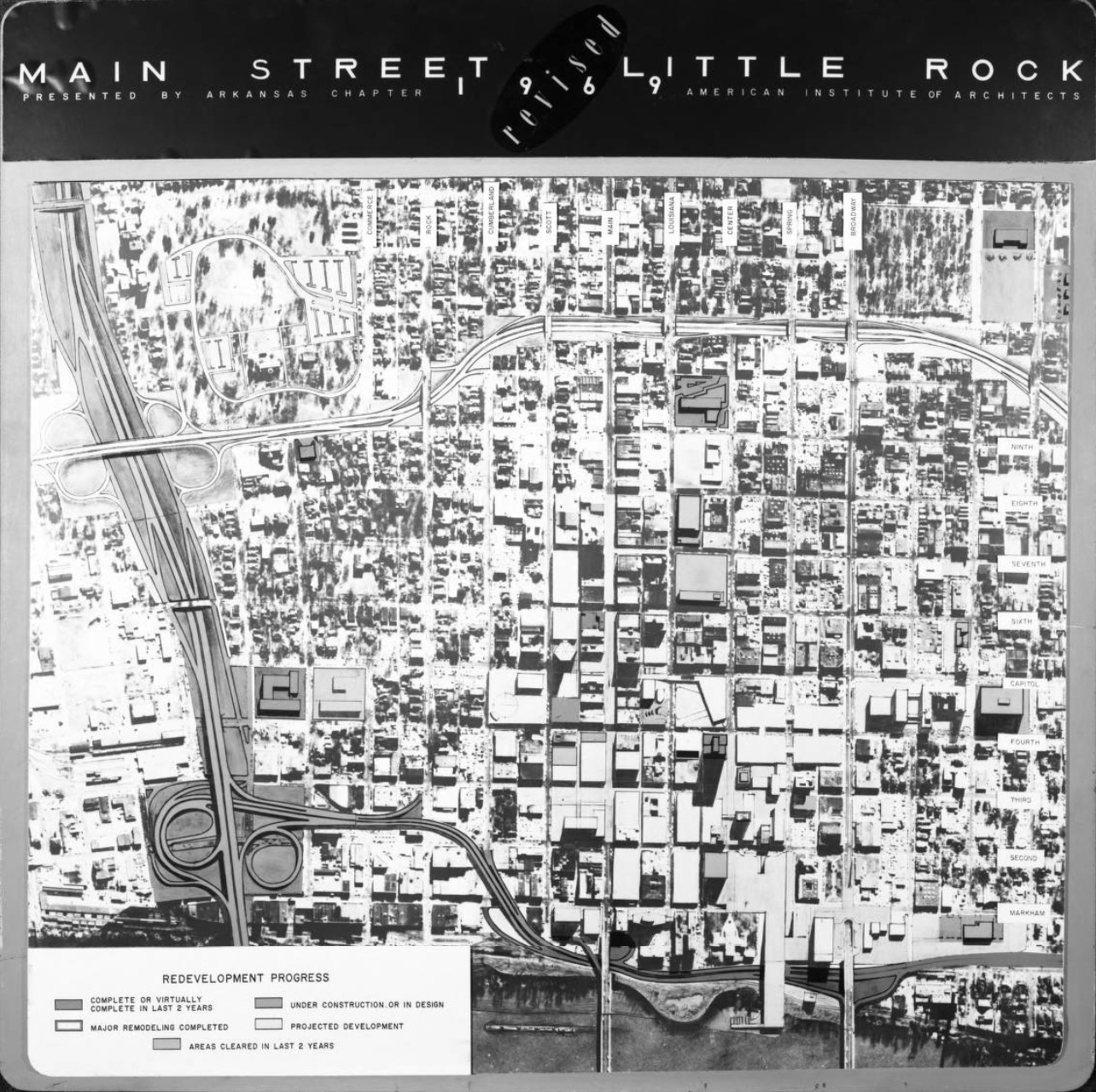

CS: I would say a joyful weight. Little Rock is more geographically segregated now than in 1957, when the Little Rock Nine integrated Central High School. The museum is located at the corner of Broadway and Ninth Street in downtown Little Rock, which historically was the Black business district in the area until the 1960s. As a result of urban renewal, Interstate 630 cuts through the middle of the district. Our building would have sat as an anchor-point as you enter the district, and it would have continued behind us to Philander Smith College, which is the HBCU—located now on the other side of the highway. When the highway was built businesses closed and African American residents moved to the south and eastern parts of the city, and whites moved to the west. This changed the landscape of downtown Little Rock in a lot of ways. It has impacted the way resources are shared across the city, the way communities are heard or not heard, and the way people and stories are silenced in Little Rock and also across the state. The best thing about my job is that I get to tell and provide space for those untold stories to be on display. That, to me, is everything.

The project that captures it perfectly is what we’re working on with Perrion Hurd. We commissioned him to do these massive, 20-foot-tall banners around our building. Perrion got interested in art when he was 8 years old. He saw this mural of a Black kid in Memphis when he was growing up. One day as he was walking by he asked the artist about it, so the guy let him do a little paint touch-up on the mural. This inspired him to become an artist, which he pursued. And now, as an adult, here’s a museum that not only appreciates his work but does an exhibition based around his artwork.

SW: What are some things that you had no idea the job entailed, going in, but that are very much part of your day-to-day?

CS: There is so much politics with the job. It’s almost like I have to have this Olivia Pope side of my brain that’s thinking all the time about how to solve a problem, how to fix a problem, how to make something or take something that was literally rotten lemons and make lemonade out of it. It’s not something you learn in school and you really don’t understand until you have to do it. But through it all I’ve tried to have integrity and be transparent. That has done a great deal in building people’s trust. There are plenty of people who do not want to work with the state, but they’re willing to work with me, or they’re willing to work with the museum, or they’re willing to work with another staff member. And so to be able to start at that place and rebuild a relationship has been cool and humbling and exhausting, all at the same time.

The project that captures it perfectly is what we’re working on with Perrion Hurd. We commissioned him to do these massive, 20-foot-tall banners around our building. Perrion got interested in art when he was 8 years old. He saw this mural of a Black kid in Memphis when he was growing up. One day as he was walking by he asked the artist about it, so the guy let him do a little paint touch-up on the mural. This inspired him to become an artist, which he pursued. And now, as an adult, here’s a museum that not only appreciates his work but does an exhibition based around his artwork.

SW: What are some things that you had no idea the job entailed, going in, but that are very much part of your day-to-day?

CS: There is so much politics with the job. It’s almost like I have to have this Olivia Pope side of my brain that’s thinking all the time about how to solve a problem, how to fix a problem, how to make something or take something that was literally rotten lemons and make lemonade out of it. It’s not something you learn in school and you really don’t understand until you have to do it. But through it all I’ve tried to have integrity and be transparent. That has done a great deal in building people’s trust. There are plenty of people who do not want to work with the state, but they’re willing to work with me, or they’re willing to work with the museum, or they’re willing to work with another staff member. And so to be able to start at that place and rebuild a relationship has been cool and humbling and exhausting, all at the same time.

SW: Are there aspects of the job that maybe you imagined you might not enjoy but actually turned out to enjoy a great deal?

CS: I grew up without seeing Blackness represented at all, or when it was represented it was in a negative way. Here I get to pour out all these amazing, positive examples, not as a place to tokenize people or to hold them up as “the standard.” But to say, “Look at the beauty of Black people. Look how amazing Black people are. Look and see what God has created in Black people, that He’s uniquely written a story and gifted us in the midst of oppression, in the midst of struggle, look at all of the ways that Black people have thrived and not just survived.” Because I was told, “we were slaves, white people freed us, Martin Luther King, white people again.” That’s the story of Black history in textbooks. But now I’m in a position where I get to showcase the full beauty of Blackness and talk about it every day as part of my job.

SDB: Can you just talk about the intentionality of selling products made by Black artists, creatives, and business owners in your gift shop? What was it like before, and how were you able to build these partnerships and relationships with different business owners and entrepreneurs in the community?

CS: The store originally only had books and it felt kind of like a library. There was branded merchandise and also some Black Lives Matter t-shirts, which caused a lot of controversy within the Department and were pulled. The Black community was really upset about the decision. So I started brainstorming how to use this situation as an opportunity, and do something different. Around the same time I was looking to buy a Christmas gift for my mom and I wanted to send her something from the museum store, but the only thing I could send was a book. So I thought, “What is it that makes our store unique? Can we showcase Arkansas-made items that are also crafted by Black folks, that show the rich legacy and history of Black creatives?” That’s where the brainchild for “Arkansas Made, Black-Crafted” came from. When people think about creatives here they imagine older white guys in the mountains making Ozark kinds of things. I love subverting those things and showing there's a lot of diversity, and rich cultural history and heritage of Black folks making things.

I have to give full credit to Kelli Hall who is our museum store manager. She really put out feelers and asked around. We started with Tracey Dawson of Big and Purty Custom Clutches from Etsy and convinced her to sell her merchandise in the store. She introduced us to her friend who makes jewelry, who introduced us to more friends and more friends after that. So this network grew from that initial relationship. As we started selling headscarves, jewelry, soaps, and even food, we learned that many [vendors] had never had a small-business class, and didn’t know about trademarking and copyright. So we called the Small Business Association for Arkansas and asked if we could partner to do a series of workshops for our Black craft makers and host them at the museum, and feature one of our makers to talk about it from their perspective. In December 2019, we launched the next phase of it called “Arkansas Made, Black Craft Junior Edition,” which is all young makers who are artists and designers. I’m excited to see where it’s going to go and how we’re going to be able to encourage Black entrepreneurship. We want to use our position and our space to promote them because we value what they’re doing.

CS: I grew up without seeing Blackness represented at all, or when it was represented it was in a negative way. Here I get to pour out all these amazing, positive examples, not as a place to tokenize people or to hold them up as “the standard.” But to say, “Look at the beauty of Black people. Look how amazing Black people are. Look and see what God has created in Black people, that He’s uniquely written a story and gifted us in the midst of oppression, in the midst of struggle, look at all of the ways that Black people have thrived and not just survived.” Because I was told, “we were slaves, white people freed us, Martin Luther King, white people again.” That’s the story of Black history in textbooks. But now I’m in a position where I get to showcase the full beauty of Blackness and talk about it every day as part of my job.

SDB: Can you just talk about the intentionality of selling products made by Black artists, creatives, and business owners in your gift shop? What was it like before, and how were you able to build these partnerships and relationships with different business owners and entrepreneurs in the community?

CS: The store originally only had books and it felt kind of like a library. There was branded merchandise and also some Black Lives Matter t-shirts, which caused a lot of controversy within the Department and were pulled. The Black community was really upset about the decision. So I started brainstorming how to use this situation as an opportunity, and do something different. Around the same time I was looking to buy a Christmas gift for my mom and I wanted to send her something from the museum store, but the only thing I could send was a book. So I thought, “What is it that makes our store unique? Can we showcase Arkansas-made items that are also crafted by Black folks, that show the rich legacy and history of Black creatives?” That’s where the brainchild for “Arkansas Made, Black-Crafted” came from. When people think about creatives here they imagine older white guys in the mountains making Ozark kinds of things. I love subverting those things and showing there's a lot of diversity, and rich cultural history and heritage of Black folks making things.

I have to give full credit to Kelli Hall who is our museum store manager. She really put out feelers and asked around. We started with Tracey Dawson of Big and Purty Custom Clutches from Etsy and convinced her to sell her merchandise in the store. She introduced us to her friend who makes jewelry, who introduced us to more friends and more friends after that. So this network grew from that initial relationship. As we started selling headscarves, jewelry, soaps, and even food, we learned that many [vendors] had never had a small-business class, and didn’t know about trademarking and copyright. So we called the Small Business Association for Arkansas and asked if we could partner to do a series of workshops for our Black craft makers and host them at the museum, and feature one of our makers to talk about it from their perspective. In December 2019, we launched the next phase of it called “Arkansas Made, Black Craft Junior Edition,” which is all young makers who are artists and designers. I’m excited to see where it’s going to go and how we’re going to be able to encourage Black entrepreneurship. We want to use our position and our space to promote them because we value what they’re doing.

![Image: The diploma that Carlotta Walls received upon graduation from Little Rock Central High School, July 8, 1960. The diploma consists of black ink printed on white paper; [Central High School ] is printed at the top along with an illustration of the school building. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of Carlotta Walls LaNier.](https://freight.cargo.site/t/original/i/9d454106189d67c76704234b962cc5894657f58aa3c6c2913ddd770f48c3fdb8/NMAAHC-2012_117_3_001.jpg)

![Image: Envelope for a letter from the Dollars for Daisy Bates Trust Fund. The envelope has [D F Daisy / The DOUGLASS / STATE / BANK] in black text in the upper left from Kansas City, Kansas. The center of the envelope has printed text which reads [Rev. V.K. Stokes / Trinity Baptist Church / 1526 McCullob [sic] St. / Baltimore, Md.]. There are three stamps in blue ink along the top, one for auto loans and two postage marks. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of the Stokes/Washington Family.](https://freight.cargo.site/t/original/i/665c0c08bce835929208ddb9f44b17a9bdce01c615b97e5420bcba6215565618/NMAAHC-2017_14_5b_001.jpg)

SW: How do you interact with the concepts of documenting the loss and/or capture of Black cultural heritage collections, sites, and memory in your work? How much of your work is about either preventative documentation and capture or a sort of post-memorial about loss?

CS: My work is both of those things. In a perfect world, people call us before they throw something away.

Last year, we did an exhibit on the culture of African-American hair. Most of the objects came from the Velvatex College of Beauty Culture, founded by a Black woman, Mrs. M.E. Patterson. They have been in business for 91 years and are the oldest Black woman-owned business in Arkansas, and probably one of the oldest in the country. Getting to partner with them on the exhibit was an incredible opportunity to tell the story of Black women who found agency through their hair, through creating businesses, through educating people about hair, and the professionalism of beauty colleges and cosmetology. After the exhibition, they donated their collection to the museum. It’s a relationship that we are eager to continue.

Then there’s also the loss piece. We did a program last year about the Wrightsville 21. The Arkansas Negro Boys' Industrial School in Wrightsville was a prison-work farm for youth, and in 1959 the building burned down with 21 boys inside. Governor Orval Faubus was in office and the way the state handled the casualties was very much of its time. There were some articles in the newspaper, but after it happened, it disappeared from the sort of collective memory and the discourse. It wasn’t talked about. We did a program with researcher-journalist Chris Stockley who wrote Black Boys Burning. We invited the survivors and families of victims as well as the mayor of Wrightsville. We read the names of the boys who died. And, to my knowledge, that’s probably the first time it's ever been done. The more I do this work, the more I realize and understand the power in saying their names and not letting their existence be forgotten. This is a way in which we try to stand up against forgetting because it’s easy to forget things that we don’t want to remember.

SW: What are some of the biggest threats to sustaining Black cultural heritage and stewarding those narratives? What are some of the biggest threats to doing that work, in these types of smaller institutions focused on Black history?

CS: By far, across the board for Black museums, funding is a huge threat, and it’s the lack of funding. I have colleagues who have buildings but don’t have money to operate them. I have colleagues that don’t have a building, and they’re trying to fundraise to build one, and have been for years. It costs money to put together exhibits and programs. Most Black history museums like the older ones in Chicago, D.C., and Detroit, have been able to build funding programs, but they’re still not well-heeled as white institutions, but they have been able to raise money. Younger organizations that have been around for 5-20 years don’t start with that.

SW: What basically comprises the funding model for museums, especially ones like yours?

CS: Almost 100 percent of our operating (income) comes through state tax dollars and an endowment from the state. Most museums have a 501(c)(3) status and rely on donations from large corporations or ticket sales. But ticket sales aren’t enough to support the work of a large staff. It’s a double-edged sword. You want more people in the door, but you need money to make money. How do you balance both of those things? At slightly larger institutions, there may be a development officer on staff, and their executive director may spend a great deal of time fundraising, writing grants, meeting with corporate donors for sponsorship to underwrite programs. For most Black museums, part of that structural support is that it takes time to write a grant, especially if you serve as the director, and maybe the custodian too—because you can’t afford one—and also do the education programs. That's a lot of work.

Then there is how we both honor the legacy and the radical roots of Black museums, while also reimagining the future, and understanding it from the next generation's perspective. That’s something all museums face, being willing to both be grounded in who you are but also not threatened by the opportunity of change and the opportunity of doing something different than what you’ve done before.

SW: What do you think is important for people to know about keeping and sustaining Black cultural heritage, collections, etc?

CS: Tell the truth about history. It doesn’t mean that you have to display photos of lynching victims because that’s not a way to honor them. At my museum, we tell people that a man's body hung from here. But we also tell the story of how that was one day in his life, that’s not who he was, just a lynching victim. He was also a whole person with a family and a community.

Last year, we did an exhibit on racism and memorabilia about the Elaine Massacre where over 270 African Americans were murdered in Elaine, Arkansas, in 1919. We realized we couldn’t send people through an entire exhibit talking about hate and then dump them out in the hallway. We needed resources. So we reached out to therapists and compiled a list of therapy resources people could call. There’s the talking about Black history, but then everything that’s come out of talking about Black history. And doing it in a way where we do not shy away from the truth but really try to press into the truth, and press into this idea that if we can talk about it then we can begin to move forward from it.

CS: My work is both of those things. In a perfect world, people call us before they throw something away.

Last year, we did an exhibit on the culture of African-American hair. Most of the objects came from the Velvatex College of Beauty Culture, founded by a Black woman, Mrs. M.E. Patterson. They have been in business for 91 years and are the oldest Black woman-owned business in Arkansas, and probably one of the oldest in the country. Getting to partner with them on the exhibit was an incredible opportunity to tell the story of Black women who found agency through their hair, through creating businesses, through educating people about hair, and the professionalism of beauty colleges and cosmetology. After the exhibition, they donated their collection to the museum. It’s a relationship that we are eager to continue.

Then there’s also the loss piece. We did a program last year about the Wrightsville 21. The Arkansas Negro Boys' Industrial School in Wrightsville was a prison-work farm for youth, and in 1959 the building burned down with 21 boys inside. Governor Orval Faubus was in office and the way the state handled the casualties was very much of its time. There were some articles in the newspaper, but after it happened, it disappeared from the sort of collective memory and the discourse. It wasn’t talked about. We did a program with researcher-journalist Chris Stockley who wrote Black Boys Burning. We invited the survivors and families of victims as well as the mayor of Wrightsville. We read the names of the boys who died. And, to my knowledge, that’s probably the first time it's ever been done. The more I do this work, the more I realize and understand the power in saying their names and not letting their existence be forgotten. This is a way in which we try to stand up against forgetting because it’s easy to forget things that we don’t want to remember.

SW: What are some of the biggest threats to sustaining Black cultural heritage and stewarding those narratives? What are some of the biggest threats to doing that work, in these types of smaller institutions focused on Black history?

CS: By far, across the board for Black museums, funding is a huge threat, and it’s the lack of funding. I have colleagues who have buildings but don’t have money to operate them. I have colleagues that don’t have a building, and they’re trying to fundraise to build one, and have been for years. It costs money to put together exhibits and programs. Most Black history museums like the older ones in Chicago, D.C., and Detroit, have been able to build funding programs, but they’re still not well-heeled as white institutions, but they have been able to raise money. Younger organizations that have been around for 5-20 years don’t start with that.

SW: What basically comprises the funding model for museums, especially ones like yours?

CS: Almost 100 percent of our operating (income) comes through state tax dollars and an endowment from the state. Most museums have a 501(c)(3) status and rely on donations from large corporations or ticket sales. But ticket sales aren’t enough to support the work of a large staff. It’s a double-edged sword. You want more people in the door, but you need money to make money. How do you balance both of those things? At slightly larger institutions, there may be a development officer on staff, and their executive director may spend a great deal of time fundraising, writing grants, meeting with corporate donors for sponsorship to underwrite programs. For most Black museums, part of that structural support is that it takes time to write a grant, especially if you serve as the director, and maybe the custodian too—because you can’t afford one—and also do the education programs. That's a lot of work.

Then there is how we both honor the legacy and the radical roots of Black museums, while also reimagining the future, and understanding it from the next generation's perspective. That’s something all museums face, being willing to both be grounded in who you are but also not threatened by the opportunity of change and the opportunity of doing something different than what you’ve done before.

SW: What do you think is important for people to know about keeping and sustaining Black cultural heritage, collections, etc?

CS: Tell the truth about history. It doesn’t mean that you have to display photos of lynching victims because that’s not a way to honor them. At my museum, we tell people that a man's body hung from here. But we also tell the story of how that was one day in his life, that’s not who he was, just a lynching victim. He was also a whole person with a family and a community.

Last year, we did an exhibit on racism and memorabilia about the Elaine Massacre where over 270 African Americans were murdered in Elaine, Arkansas, in 1919. We realized we couldn’t send people through an entire exhibit talking about hate and then dump them out in the hallway. We needed resources. So we reached out to therapists and compiled a list of therapy resources people could call. There’s the talking about Black history, but then everything that’s come out of talking about Black history. And doing it in a way where we do not shy away from the truth but really try to press into the truth, and press into this idea that if we can talk about it then we can begin to move forward from it.

So tell the truth, and commit to telling it from your view, lens, and perspective. On my wall, I have, “your silence will not protect you” (from Audre Lorde). Don’t be silent. Stand up! That’s what will keep the legacy of what we are doing going past our generation. When I think about decisions I make for the museum, I think about it seven generations beyond me. So not what matters to my child or what my grandchild will see, but what happens when I’m not here—what is that person going to experience when they come to the museum, and how are the decisions that I make today going to impact them? ︎

Steven D. Booth (he/him) is an archivist, researcher, and co-founder of The Blackivists Collective. He has been with the National Archives and Records Administration since 2009 and currently manages the audiovisual collection for the Barack Obama Presidential Library. He is actively involved in the Society of American Archivists (SAA) and recently served on the governing board of the organization.

Stacie Williams (she/her) is director of the Center for Digital Scholarship at the University of Chicago Libraries, and a member of the Chicago-based Blackivists archivist collective, which works with individuals and organizations to preserve Black Chicagoland memory and culture. Her work is centered on sustainability of digital and web-based knowledge sources and equitable labor practices in cultural heritage professions. Williams was previously an advisory archivist for A People’s Archive of Police Violence in Cleveland, a 2015 oral history project that documented people’s experiences with police violence and harassment in the Cleveland metropolitan area, and a former journalist for more than 10 years. Her first book, Bizarro Worlds (Fiction Advocate), a bibliomemoir about race and gentrification, was released in 2018.