Don’t It Always Seem to Go: On the Loss and Capture of Black (re)Collections

Essay by Tempestt Hazel

“There used to be a house here...and [my] dad bought the house next door to put my grandparents in–my mom’s and my dad’s parents,” Mom explained while standing at the edge of two empty, grassy lots in the middle of a block on the south end of my hometown, Peoria, Illinois. “And [your uncle] Arthur used to live there,” she continued, pointing to another empty lot across the street. As she said this, I added three houses to my growing mental list of homes that were once owned and occupied by members of my family. So far, the list totaled six that spread across Peoria, Chicago, and also parts of Tennessee where my sister recently found out, through some rediscovered family records, that her maternal grandparents once owned a home and land. My mother had no idea that the three homes had been torn down and it’s not clear what happened to them in the decades between now and when her parents left the homes and after she and all of her siblings moved out.

While standing in the middle of the lots, I tried to soak up all of the people, personal landmarks, and the sparks from her million memories that made it to the front of her mind. I attempted to visualize, from her descriptions, what Smith Street looked like for Mom in the 50s and 60s: “There were hedges right there, we would play volleyball over them.” “[Dad kept] the dogs, the chickens, and the garden over here.” “The garage used to be here with the two refrigerator-freezers in them—one for the fish, and one for the other meat that dad hunted and processed.” “We had so much fun here…”

Watching my mother remake her home through fragmented recollections in a now vacant space felt like a familiar practice for those of us who, like my family, have stories with many fractures and points where the details begin to disappear. There are often abrupt stops and gaps in family and community lineages because those stories weren’t always documented or easily circulated. Those stories, objects, and records are also sometimes tangled in precariousness due to a combination of difficult circumstances. Elders who construct memory bridges and provide the details that fill the fissures of photographs and records sometimes pass away before that knowledge is captured. Or, family and community histories succumb to conflicting stories and mystery around what happened to the keepsakes that were in long-cleared closets, basements, or storage trunks, and were lost over time during family migratons and formal or ad hoc estate transitions.

Talking with my mother about her history was also a potent reminder of who and what the original repositories of Black legacies are: the people through which histories and traditions are housed and carried forward, and the private or community spaces where collections were intentionally or naturally accumulated.

These repositories, including the now institutionally-housed ones that still endure today, often feel like nothing short of miracles when remembering that they exist within a country that has consistently prevented and actively resisted the formation, maintenance, and accessibility of autonomous and thriving Black histories and spaces. Despite everything working to convince us otherwise, these collections still stand as evidence that an unquantifiable and, in some cases, unrecoverable Black cultural richness exists and that Black people have always been aware of the need to document and carry on our stories ourselves. And through tireless and relatively quiet maneuvers, these repositories and people have withstood within a country whose founders saw the erasure of Black and Indigenous culture, language, and history as something as critical to the making of the United States as creating an exclusive, distorted, and self-serving version of freedom and democracy.

While standing in the middle of the lots, I tried to soak up all of the people, personal landmarks, and the sparks from her million memories that made it to the front of her mind. I attempted to visualize, from her descriptions, what Smith Street looked like for Mom in the 50s and 60s: “There were hedges right there, we would play volleyball over them.” “[Dad kept] the dogs, the chickens, and the garden over here.” “The garage used to be here with the two refrigerator-freezers in them—one for the fish, and one for the other meat that dad hunted and processed.” “We had so much fun here…”

Watching my mother remake her home through fragmented recollections in a now vacant space felt like a familiar practice for those of us who, like my family, have stories with many fractures and points where the details begin to disappear. There are often abrupt stops and gaps in family and community lineages because those stories weren’t always documented or easily circulated. Those stories, objects, and records are also sometimes tangled in precariousness due to a combination of difficult circumstances. Elders who construct memory bridges and provide the details that fill the fissures of photographs and records sometimes pass away before that knowledge is captured. Or, family and community histories succumb to conflicting stories and mystery around what happened to the keepsakes that were in long-cleared closets, basements, or storage trunks, and were lost over time during family migratons and formal or ad hoc estate transitions.

Talking with my mother about her history was also a potent reminder of who and what the original repositories of Black legacies are: the people through which histories and traditions are housed and carried forward, and the private or community spaces where collections were intentionally or naturally accumulated.

These repositories, including the now institutionally-housed ones that still endure today, often feel like nothing short of miracles when remembering that they exist within a country that has consistently prevented and actively resisted the formation, maintenance, and accessibility of autonomous and thriving Black histories and spaces. Despite everything working to convince us otherwise, these collections still stand as evidence that an unquantifiable and, in some cases, unrecoverable Black cultural richness exists and that Black people have always been aware of the need to document and carry on our stories ourselves. And through tireless and relatively quiet maneuvers, these repositories and people have withstood within a country whose founders saw the erasure of Black and Indigenous culture, language, and history as something as critical to the making of the United States as creating an exclusive, distorted, and self-serving version of freedom and democracy.

What we are fortunate enough to know now, which counters any claim that we have no significant history, and what some from past generations didn’t have readily available, is the research and evidence that addresses gaps in Black history, and a deeper understanding around approaches to preservation that were inherent to our ancestors. As Dorothy Porter Wesley described back in 1957, the “anthropologists, linguists, and historians have gone far to correct this ignorant opinion [and] have proved that many African people of high culture have possessed an historical sense, and further, that their trained memories and prodigious fund of legend have served as the actual conservators of their history.”1 She goes on to reference Maurice Delafosse’s use of the term “living books” when talking about Africa’s earliest libraries that were, in fact, people: court historians, artists, storytellers, poets, musicians, and others who carried the responsibility of being “walking encyclopedias” and passing on tribal stories, proverbs, mythologies, genealogies, beliefs, and root traditions. It is a form of history-keeping that is still practiced today.

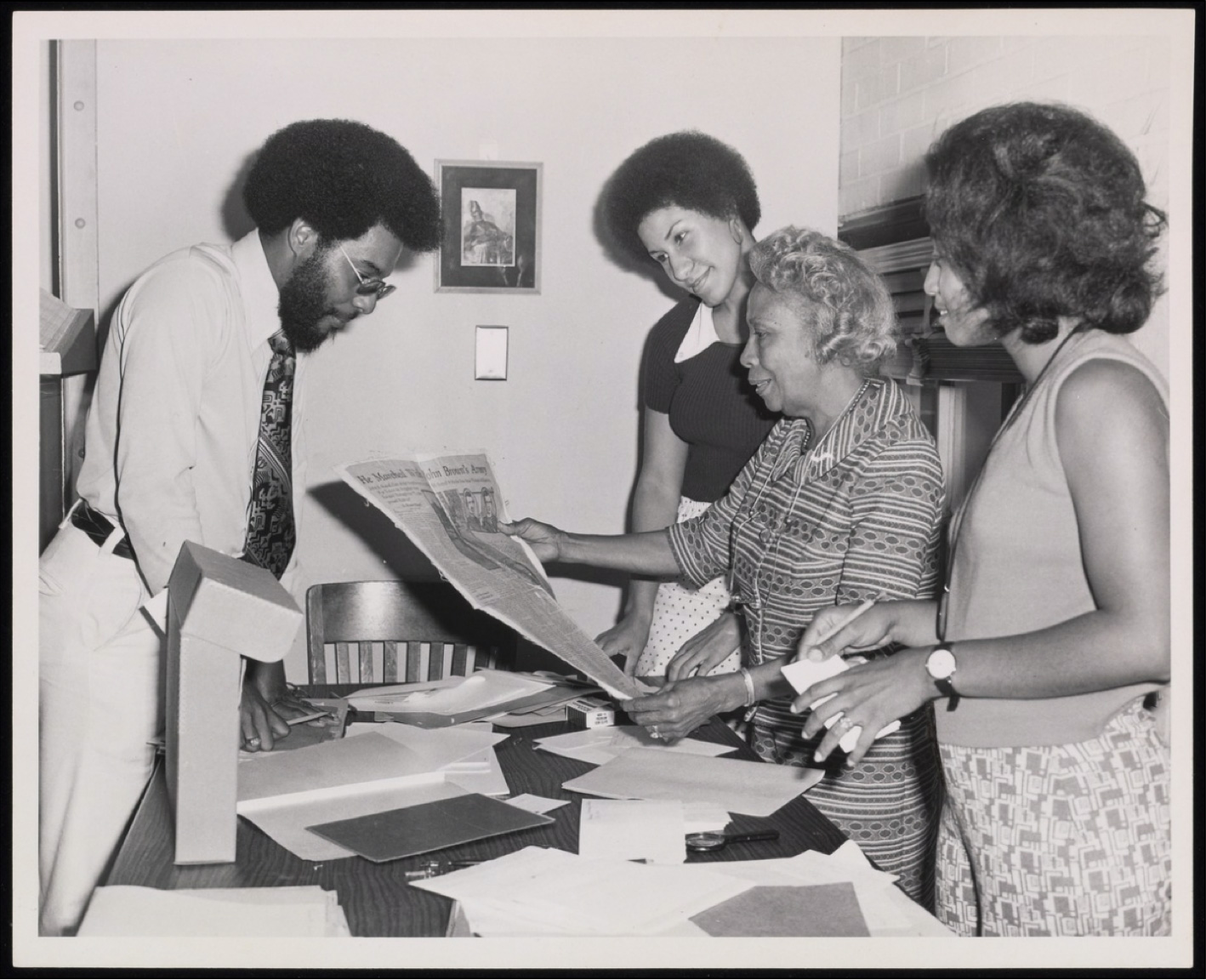

Alongside these history-making traditions, many of the collections used to anchor and establish the Black research institutions that are beloved today can be traced back to individuals who also knew the importance of collecting and preserving Black histories and memories and who took it upon themselves to make sure these collections were complex, nuanced, thorough, and placed in good hands. Dorothy Porter Wesley was one of those individuals. A foremother of decolonizing libraries and their classification systems as well as a defining force in the valuation of library materials authored by Black people, Porter was one of the main librarians and curators responsible for developing the collections that would help to establish the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center at Howard University in 1973. Starting with the private collections and libraries of Jesse E. Moorland and Arthur B. Spingarn, the center’s holdings were established on abolitionist texts, narratives of enslaved peoples, and the global Black experience and diaspora.

Then, there was Arturo Alfonso Schomburg, an Afro-Puerto Rican activist, historian, and curator who built an unbelievable personal collection that would eventually become the heart of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. According to biographer Elinor Sinnette, Schomburg started collecting as a reaction to his fifth grade teacher who told him that “[B]lack people had no history, no heroes, no great moments.” And as the story is told, in 1926 his wife urged him to sell his collection to the Carnegie Corporation–who then donated it to the New York Public Library–because the 5,000 books, 3,000 manuscripts, 2,000 etchings and paintings, and thousands of pamphlets that Schomburg had accumulated over the years started to take over his home. Six years after the collection was used to establish the New York Public Library’s Division of Negro Literature, History and Prints, Schomburg was brought on as curator of the division and was able to continue building and expanding his collection.

Alongside these history-making traditions, many of the collections used to anchor and establish the Black research institutions that are beloved today can be traced back to individuals who also knew the importance of collecting and preserving Black histories and memories and who took it upon themselves to make sure these collections were complex, nuanced, thorough, and placed in good hands. Dorothy Porter Wesley was one of those individuals. A foremother of decolonizing libraries and their classification systems as well as a defining force in the valuation of library materials authored by Black people, Porter was one of the main librarians and curators responsible for developing the collections that would help to establish the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center at Howard University in 1973. Starting with the private collections and libraries of Jesse E. Moorland and Arthur B. Spingarn, the center’s holdings were established on abolitionist texts, narratives of enslaved peoples, and the global Black experience and diaspora.

Then, there was Arturo Alfonso Schomburg, an Afro-Puerto Rican activist, historian, and curator who built an unbelievable personal collection that would eventually become the heart of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. According to biographer Elinor Sinnette, Schomburg started collecting as a reaction to his fifth grade teacher who told him that “[B]lack people had no history, no heroes, no great moments.” And as the story is told, in 1926 his wife urged him to sell his collection to the Carnegie Corporation–who then donated it to the New York Public Library–because the 5,000 books, 3,000 manuscripts, 2,000 etchings and paintings, and thousands of pamphlets that Schomburg had accumulated over the years started to take over his home. Six years after the collection was used to establish the New York Public Library’s Division of Negro Literature, History and Prints, Schomburg was brought on as curator of the division and was able to continue building and expanding his collection.

And there’s Chicago’s own Vivian G. Harsh, who was a librarian and collector, whose name you will usually see followed by a list of firsts. She is considered Chicago’s first Black librarian. In 1932, she also became the first librarian to take the helm of the George Cleveland Hall Branch of the Chicago Public Library in Bronzeville, which was the first public library branch in the city to be built in a Black neighborhood. She is the namesake of the Vivian G. Harsh Research Collection at the Carter G. Woodson Regional Library, which is the largest Black history and literature collection of its kind in the Midwest. Originally named the Special Negro Collection and housed at the Hall Branch, its earliest items came into the collection in 1929 with 100 books and monographs from the private library of Charles Bentley, a dentist and founding member of the NAACP. With the help of Harsh’s colleagues and fellow librarians Marian G. Hadley and Charlemae Hill Rollins, and despite a lack of adequate funding to do so, she began building the collection by traveling across the country searching for first editions and by creating an environment at the library that attracted countless prominent writers of the time, including Zora Neale Hurston and Gwendolyn Brooks as well as Langston Hughes and Richard Wright, who both have manuscripts and materials in the collection.

In Chicago, there is also a legacy of collectors who built their repositories independent of any established institution and decided to make them directly accessible in various ways to their communities and the wider public. I think of Dr. Margaret T. Burroughs, an educator, poet, artist, and activist who helped found the Ebony Museum of Negro History and Culture in her and her husband’s living room in 1961. The Ebony Museum would later be renamed the DuSable Museum of African American History and be moved to a larger location in Washington Park because the collection, which is made up in large part by the Burroughs’ personal holdings and those of other collectors, outgrew their home. The DuSable Museum’s archives now, too, include countless boxes of Dr. Burroughs’ papers, records, and scrapbooks.

In Chicago, there is also a legacy of collectors who built their repositories independent of any established institution and decided to make them directly accessible in various ways to their communities and the wider public. I think of Dr. Margaret T. Burroughs, an educator, poet, artist, and activist who helped found the Ebony Museum of Negro History and Culture in her and her husband’s living room in 1961. The Ebony Museum would later be renamed the DuSable Museum of African American History and be moved to a larger location in Washington Park because the collection, which is made up in large part by the Burroughs’ personal holdings and those of other collectors, outgrew their home. The DuSable Museum’s archives now, too, include countless boxes of Dr. Burroughs’ papers, records, and scrapbooks.

Or I think of Daniel Texidor Parker, a professor, author, and former student of Dr. Burroughs during her time teaching at DuSable High School, who was inspired by his mother and Dr. Burroughs to start collecting. His collection includes over 450 original works by Black artists in Chicago and of the wider diaspora. He is a co-founder of the Black collectors group Diasporal Rhythms with Patric McCoy, an avid bicyclist, photographer, former environmental scientist, and collector with over 1,300 artworks hanging in his home and even more photographs and pieces of ephemera documenting Black life and culture stored away. With an unwavering determination to maintain the integrity of his collection and keep it intact after he transitions, McCoy and others are dreaming of a plan to make the building where he lives into a home museum and art center. For years Parker and McCoy, along with other members of Diasporal Rhythms, have opened their homes to students and tour groups in order to show what it looks like to build a Black collection that is global in scope, local in emphasis, and personal through-and-through, one relatively affordable piece at a time.

But for each story of gains, there is a comparable story of loss and uncertainty. As any archivist will tell you, it takes a mighty amount of time, physical space, people-power, knowledge, and resources to organize, care for, and maintain any collection, whether for an institution, a family, or a community. That, combined with an overall lack of Black museums, libraries, and repositories that have the capacity to take in and adequately house these materials while making them accessible locally, regionally, digitally, or otherwise, leaves many archives and potential seeds of archives battling depreciation, neglect, and inaccessibility. They are the casualties of circumstance and limited options.

But for each story of gains, there is a comparable story of loss and uncertainty. As any archivist will tell you, it takes a mighty amount of time, physical space, people-power, knowledge, and resources to organize, care for, and maintain any collection, whether for an institution, a family, or a community. That, combined with an overall lack of Black museums, libraries, and repositories that have the capacity to take in and adequately house these materials while making them accessible locally, regionally, digitally, or otherwise, leaves many archives and potential seeds of archives battling depreciation, neglect, and inaccessibility. They are the casualties of circumstance and limited options.

Many people who have or inherit these materials don’t know what they have and have no clear or easy way of finding out. Many of the ideal repositories for these materials don’t have adequate resources to build the infrastructure needed to take them in, catalog them, and make them available. Then, the people with decision-making power around acquisitions within institutions—especially predominantly white institutions—are still (in a post-Dorothy Porter Wesley world) limited in their understanding and valuing of Black culture and heritage, or have strong opinions around what qualifies as preservation-worthy Black culture, which impacts their curatorial choices. There are several significant examples of institutions, including Black-led and local institutions, that are missing opportunities to work collaboratively and creatively to explicitly express through acquisition any beliefs they have in this history’s value to Chicago and its residents. And sometimes when the value of these materials is acknowledged, those collections often go for embarrassingly less than they are worth to the highest bidder, which means definitive Chicago collections are sometimes relocated to other parts of the state or country and detached from their essential geographical context. Also, private motivations and moves such as real estate gains, urban renewal, displacement, or public sector shortfalls lead to the erasure or capitalization of culture.

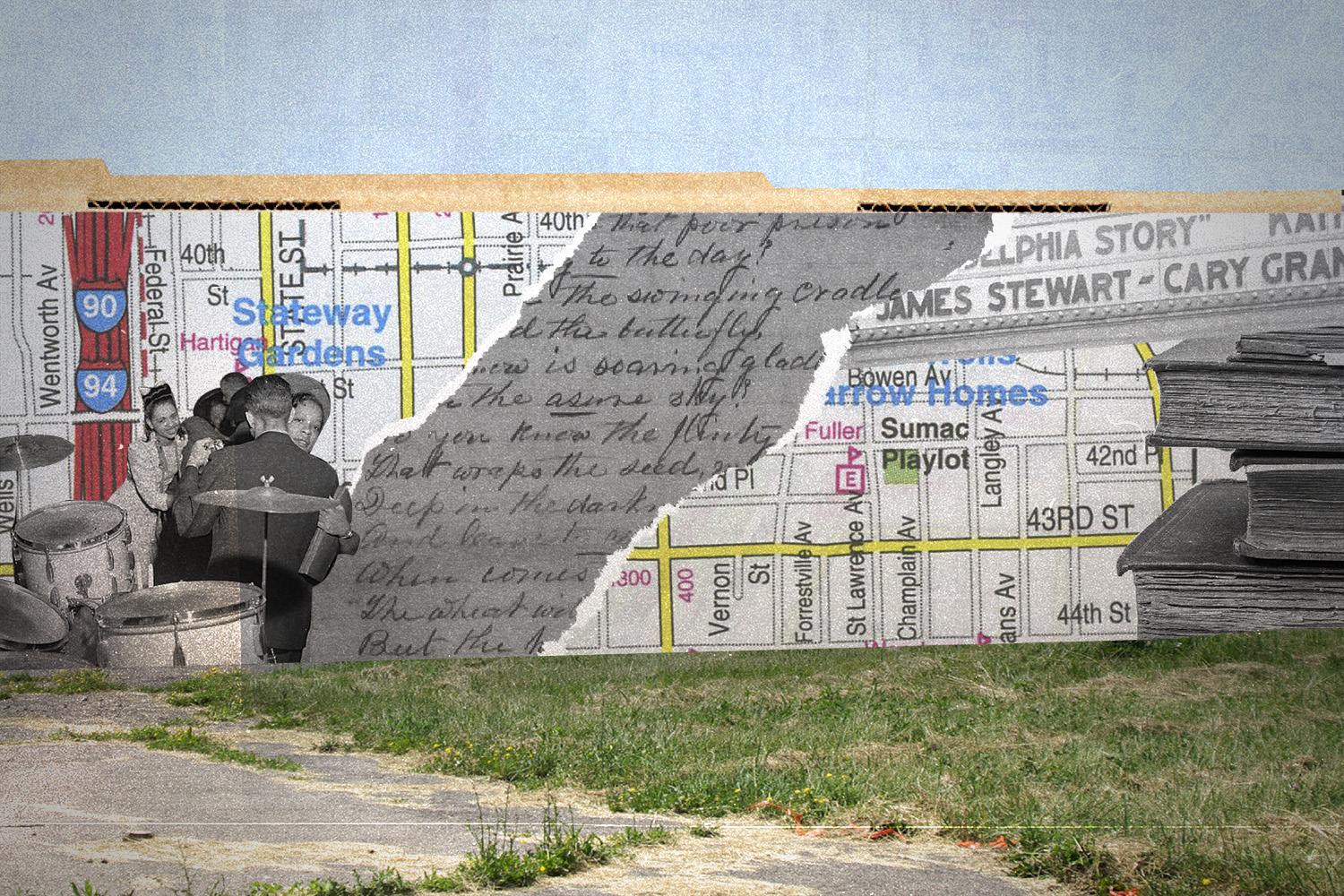

It is for these reasons and a host of others that we have to go to Urbana-Champaign to explore Gwendolyn Brooks’ archives, or to Brooklyn to see a significant body of work by AfriCOBRA. It is why we can no longer marvel at William “Bill” Walker’s All of Mankind mural at the Stranger’s Home Missionary Baptist Church near where Cabrini-Green once stood. It is why a collective rage bubbled up when we heard that works by Kerry James Marshall that were housed in public and neighborhood spaces were ending up in auctions at Christie’s and Sotheby’s. It is why there continues to be collective concern around lack of transparency when expert staff was suddenly laid off at the Center for Black Music Research. It is why the John H. Johnson Publishing Company archives, research library, and original building are scattered across an unwieldy list of owners and entities. It is why the work to piece our history together and to relocate the stories is never-ending.

Each of these accounts provoke questions of how, why, and under what circumstances are Black collections made, unmade, institutionalized, kept, moved, or lost. Increased instances of loss and heartbreak over the past several years–and what often reads as a lack of concern, accountability, transparency and creative thinking around Chicago’s Black collections–made me wonder what it would look like to place these losses side-by-side and to see some visible representation of the culture that is being discreetly erased, destabilized, and pulled in different directions. But I didn’t want to exclusively focus on the losses when acknowledgement and respect must be paid to the archivists, librarians, collectors, donors, and neighborhood scholars who never questioned the value of Black cultural production and the urgency of its preservation, and have stewarded the physical and digital manifestations of our cultural breadth.

Each of these accounts provoke questions of how, why, and under what circumstances are Black collections made, unmade, institutionalized, kept, moved, or lost. Increased instances of loss and heartbreak over the past several years–and what often reads as a lack of concern, accountability, transparency and creative thinking around Chicago’s Black collections–made me wonder what it would look like to place these losses side-by-side and to see some visible representation of the culture that is being discreetly erased, destabilized, and pulled in different directions. But I didn’t want to exclusively focus on the losses when acknowledgement and respect must be paid to the archivists, librarians, collectors, donors, and neighborhood scholars who never questioned the value of Black cultural production and the urgency of its preservation, and have stewarded the physical and digital manifestations of our cultural breadth.

So, I created a list called A Timeline of Loss and Capture for Chicago’s Black Artworks and Collections. Organized chronologically and in no way comprehensive, the list includes archives, papers, significant artworks, iconic symbols, and collections that are housed and held in Chicago and relevant to a convergence of topics that anchor my work at the various intersections of art, culture, media, and advocacy, with an emphasis on Black communities. Its purpose is to first and foremost be a resource and a testament to what Chicago has and what we risk losing if we aren’t relentless and tenacious. It is also to create a space that allows more people to draw direct connections between what is called for in the Movement for Black Lives and the international efforts to preserve the relics, affirmations, and seeds of Black life over time–because they are inextricably linked and are in constant and urgent need of watering. And at a time of multiple crises when public dollars are limited and stretched, this list is an offering to help put into perspective and not lose sight of the critical role that Chicago Public Library,2 and libraries in general, play as safeguards, shapers, and accessible treasure-troves of history.

This list is for the curious who want to start conversations about what collections, preservation, and access looks like during our current high point of radical Black dreaming and reimagining. It's for those who want to see what we have so that we can envision new and evolved systems that lend themselves to longevity and a more complete story. It’s for those who are dreaming up spaces where we can continue to initiate and have conversations about the arenas of restorative and decolonized knowledge-creation for the kind of future that we are fighting for. ︎

This list is for the curious who want to start conversations about what collections, preservation, and access looks like during our current high point of radical Black dreaming and reimagining. It's for those who want to see what we have so that we can envision new and evolved systems that lend themselves to longevity and a more complete story. It’s for those who are dreaming up spaces where we can continue to initiate and have conversations about the arenas of restorative and decolonized knowledge-creation for the kind of future that we are fighting for. ︎

1 Quote taken from the speech “Of Men and Records in the History of the Negro” by Dorothy Porter Wesley, presented at Morgan State College, February 13, 1957, in celebration of Negro History Week.

2 Libraries, specifically the Chicago Artist Files at the Harold Washington Library, are the reason why Sixty Inches From Center began its long relationship with archives. Although it’s unbalanced in its representation of Chicago’s Black artists, an imbalance Sixty is committed to lessening, the library’s artist files are openly accessible, crowdsourced, and curated by the public.

2 Libraries, specifically the Chicago Artist Files at the Harold Washington Library, are the reason why Sixty Inches From Center began its long relationship with archives. Although it’s unbalanced in its representation of Chicago’s Black artists, an imbalance Sixty is committed to lessening, the library’s artist files are openly accessible, crowdsourced, and curated by the public.

Tempestt Hazel (she/her) is a curator, writer, and co-founder of Sixty Inches From Center, a Chicago-based arts publication and archiving initiative that has promoted and preserved the practices of BIPOC and LGBTQIA+ artists and artists with disabilities across the Midwest since 2010. Her curatorial work and work with Sixty was recently recognized with a J. Franklin Jameson Archival Advocacy Award from the Society of American Archivists (SAA). She is also the Arts Program Officer at the Field Foundation. Tempestt was born and raised in Peoria, Illinois, spent several years in the California Bay Area, and has called Chicago her second home for over 12 years.