Back Down Memory Lane: Reflections with Arlene Turner-Crawford

Interview by Stacie Williams

Arlene Turner-Crawford (she/her) works in the media of drawing, painting, printmaking and Graphic illustration. In recent years she has curated, led and participated in several public art murals and installation projects including: “Seeds of Our Culture,” a 64th St. Mural Project in collaboration with Rahmaan Statik Barnes in 2017; “Sankofa for the Earth” a Gathering Space in the Burnham Wildlife Corridor for Chicago Park District in 2016 with Dorian Sylvain and Raymond Thomas; “Up from the South,” a mural for the Bronzeville Great Migration curriculum project for NEIU’s Carruthers Center for Inner City Studies in 2012; and the Phoebe Hurst Elementary Mural Project with Kiela Smith (CPA group) in 2009. Her published artworks are included in the books Roads, Where there are No Roads by Angela Jackson, Revise the Psalm – Works Celebrating the Writing of Gwendolyn Brooks; and Contemporary Plays by African American Women edited by Sandra Adell.

"To me, art is ritual, an attempt to interpret higher expressions of life. As an image-maker, my work is expressed through both realistic and symbolic forms. This is done in an attempt to inform the viewer of a cultural continuum. My images are created through the manipulation of form, design, color, collage and assemblage.”

This interview has been condensed for length and edited for clarity.

Stacie Williams: You’ve been a part of Chicago’s Black artistic scene for decades as a mixed media artist, with an editorial perspective informed by Black musical art forms and the AfriCOBRA movement. What are some touchstones of Chicago Black artistic cultural heritage, including places or people, that you think have been lost over time?

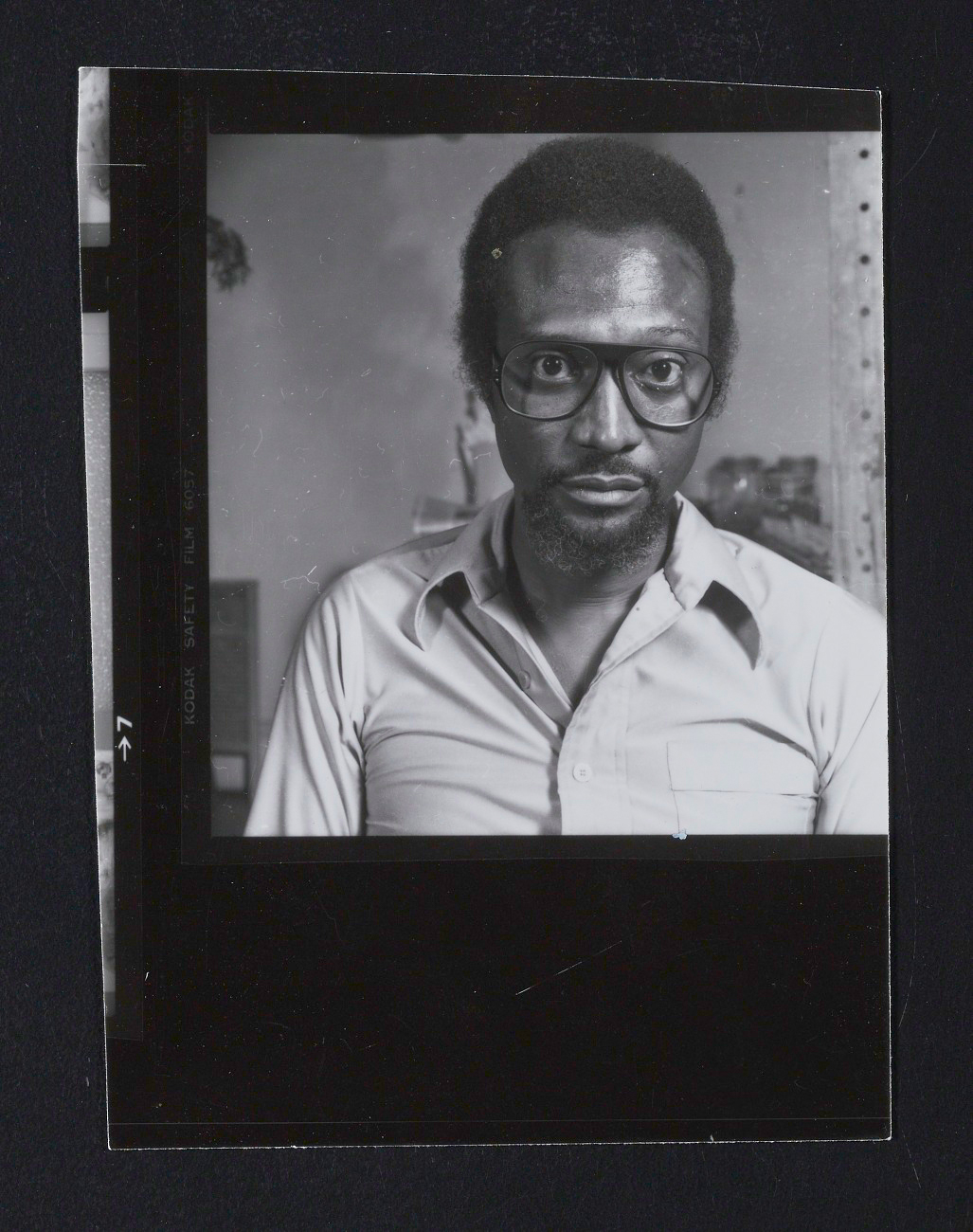

Arlene Turner-Crawford: Over time, we have lost a number of important people in that cultural arena, like Margaret Burroughs, or Jeff Donaldson, in the arts—people who were my teachers or mentors in one way or another. I got involved as a student back in high school because of Murry DePillars. He was a member of AfriCOBRA who, because of his vast expertise, was dean of the School of the Arts (at Virginia Commonwealth University). He was also one time Vice President at Chicago State (University). I don’t know how many people are familiar with Dr. Murry DePillars, but I want to recognize him as a marvelous art educator and art historian. I say because of these kinds of people, I was indoctrinated or pulled into art. I was curious. I wanted to be an artist; I wanted to be part of it.

We’ve lost a lot of our workshops, and theater companies that no longer exist. Chicago theater companies, X-BAG (Experimental Black Actors Guild), we still have Black Ensemble Theater on the West Side, but ETA (Creative Arts Foundation), although it still exists, is struggling. And ETA was started by Abena Joan Brown, she was really one of the major cultural icons in Chicago. These were the places we wanted to be seen in years ago. The Affrro-Arts Theater that Phil Cohran founded and did programming out of and allowed others to come in and program—[that] building doesn’t exist anymore.

Back in the day, there was NTU, AFAM Gallery and Cultural Center, it was off East 71st Street; the Black People’s Topographical Center, and then lots of places on East 74th and East 76th Streets. NTU was mainly a club, like the HotHouse, that would have a venue of art or spoken word. Social programming was happening at the NTU, musicians would play there, it also had spoken word or poetry. I graduated from Northern Illinois in 1971. Haki (Madhubuti’s) early bookstore was the first iteration of Transition East. There were not a lot of clubs on the South Side during the late 1960s, early 1970s that played jazz. We had to go downtown or to the North Side and besides the Jazz Showcase, clubs weren’t looking for a lot of Black jazz musicians. We would use AFAM Gallery that I believe Calvin Jones started with Lorenzo Pace for exhibiting local Black art or hearing jazz shows.

"To me, art is ritual, an attempt to interpret higher expressions of life. As an image-maker, my work is expressed through both realistic and symbolic forms. This is done in an attempt to inform the viewer of a cultural continuum. My images are created through the manipulation of form, design, color, collage and assemblage.”

This interview has been condensed for length and edited for clarity.

Stacie Williams: You’ve been a part of Chicago’s Black artistic scene for decades as a mixed media artist, with an editorial perspective informed by Black musical art forms and the AfriCOBRA movement. What are some touchstones of Chicago Black artistic cultural heritage, including places or people, that you think have been lost over time?

Arlene Turner-Crawford: Over time, we have lost a number of important people in that cultural arena, like Margaret Burroughs, or Jeff Donaldson, in the arts—people who were my teachers or mentors in one way or another. I got involved as a student back in high school because of Murry DePillars. He was a member of AfriCOBRA who, because of his vast expertise, was dean of the School of the Arts (at Virginia Commonwealth University). He was also one time Vice President at Chicago State (University). I don’t know how many people are familiar with Dr. Murry DePillars, but I want to recognize him as a marvelous art educator and art historian. I say because of these kinds of people, I was indoctrinated or pulled into art. I was curious. I wanted to be an artist; I wanted to be part of it.

We’ve lost a lot of our workshops, and theater companies that no longer exist. Chicago theater companies, X-BAG (Experimental Black Actors Guild), we still have Black Ensemble Theater on the West Side, but ETA (Creative Arts Foundation), although it still exists, is struggling. And ETA was started by Abena Joan Brown, she was really one of the major cultural icons in Chicago. These were the places we wanted to be seen in years ago. The Affrro-Arts Theater that Phil Cohran founded and did programming out of and allowed others to come in and program—[that] building doesn’t exist anymore.

Back in the day, there was NTU, AFAM Gallery and Cultural Center, it was off East 71st Street; the Black People’s Topographical Center, and then lots of places on East 74th and East 76th Streets. NTU was mainly a club, like the HotHouse, that would have a venue of art or spoken word. Social programming was happening at the NTU, musicians would play there, it also had spoken word or poetry. I graduated from Northern Illinois in 1971. Haki (Madhubuti’s) early bookstore was the first iteration of Transition East. There were not a lot of clubs on the South Side during the late 1960s, early 1970s that played jazz. We had to go downtown or to the North Side and besides the Jazz Showcase, clubs weren’t looking for a lot of Black jazz musicians. We would use AFAM Gallery that I believe Calvin Jones started with Lorenzo Pace for exhibiting local Black art or hearing jazz shows.

![Image: A black-and-white Postcard [front] for AFRICOBRA: the First Twenty Years at Nexus Contemporary Art Center, Atlanta, GA, 1990. Image shows ten AFRICOBRA members sit in an art studio or gallery. Standing left to right: Adger W. Cowans, Michael D. Harris, Jeff Donaldson, Murray DePillars, and James Phillips. Seated left to right: Napoleon Jones Henderson, Wadsworth Jarrell, Akili Ron Anderson, Frank Smith, and Nelson Stevens. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.](https://freight.cargo.site/t/original/i/5c61e284fbc2a9401903683c1c1be64ead1aade1cec161cdf0a12fb8efbb8ec8/AAA-AAA_donajeff_62723.jpg)

![Image: Postcard [back] for AFRICOBRA: the First Twenty Years at Nexus Contemporary Art Center, Atlanta, GA. Postcard shows printed details of the exhibition, including gallery address, opening reception, curator’s talk, special lectures, and the words “National Black Arts Festival, 1990.” Written by hand is the address of James Phillips ℅ Jeff Donaldson and the note, “Jeff--Please pass this on to Mr. Phillips. Isn’t he at Howard? [signature illegible]. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.](https://freight.cargo.site/t/original/i/618ddb4ddec521bd91ea689596de9eac600ddd6ffe6b474f701be5a3b14d806e/AAA-AAA_donajeff_62724.jpg)

SW: Why do you speculate that those touchstones were lost?

ATC: The economics of it. The arts usually have a select or closed audience; you have to get the word out so it becomes more economically viable for a place to survive. That’s the reason for places like NTU [to close]. It costs money to bring artists in and maintain the space. Arts might gentrify a community or area, [and] after a while, the rents go up and up as the community begins to transition, then artists can’t afford to be there anymore.

One of the other things is that we don’t develop a board of directors for arts organizations. We didn’t train them to raise money or be devoted to the work back in the 1970s, 1980s, or early 1990s. Boards were prestige kinds of things for people and they didn’t focus on the work.

Another thing that happens is that when you have the person who built the institution, sometimes those individuals really hesitate to give up power. It was someone’s passion project and they want to see every detail of it, and you have to let some of that control go. In order to maintain, it’s got to be fresh, the work always needs the means to keep living and keep moving. Your mission doesn’t change but methods have to grow and change. Young people have to be strong enough to get their points across to the older heads and then be diplomatic enough to know what there is to learn. Old heads have to commit to training the younger members.

I was part of the NCA as a student—it was an organization that Dr. (Margaret) Burroughs founded. As I got older, I became a board member who worked with Youth initiatives, because as a student I got a lot out of NCA. I went to conferences, met artists from all over the country. I met Jacob Lawrence, got to hear Elizabeth Catlett, I worked with EJ Montgomery. What NCA did for me as a student besides attending their conferences, was they’d showcase. Artists would give talks and present research. I loved Dr. Rosalind Jeffries (School of Visual Arts, NYC), a major sister in the art history realm, and everybody respected her. Her art history talks were fascinating. She would talk real fast and have all these pictures and slides, and give you information that you didn’t know existed.

ATC: The economics of it. The arts usually have a select or closed audience; you have to get the word out so it becomes more economically viable for a place to survive. That’s the reason for places like NTU [to close]. It costs money to bring artists in and maintain the space. Arts might gentrify a community or area, [and] after a while, the rents go up and up as the community begins to transition, then artists can’t afford to be there anymore.

One of the other things is that we don’t develop a board of directors for arts organizations. We didn’t train them to raise money or be devoted to the work back in the 1970s, 1980s, or early 1990s. Boards were prestige kinds of things for people and they didn’t focus on the work.

Another thing that happens is that when you have the person who built the institution, sometimes those individuals really hesitate to give up power. It was someone’s passion project and they want to see every detail of it, and you have to let some of that control go. In order to maintain, it’s got to be fresh, the work always needs the means to keep living and keep moving. Your mission doesn’t change but methods have to grow and change. Young people have to be strong enough to get their points across to the older heads and then be diplomatic enough to know what there is to learn. Old heads have to commit to training the younger members.

I was part of the NCA as a student—it was an organization that Dr. (Margaret) Burroughs founded. As I got older, I became a board member who worked with Youth initiatives, because as a student I got a lot out of NCA. I went to conferences, met artists from all over the country. I met Jacob Lawrence, got to hear Elizabeth Catlett, I worked with EJ Montgomery. What NCA did for me as a student besides attending their conferences, was they’d showcase. Artists would give talks and present research. I loved Dr. Rosalind Jeffries (School of Visual Arts, NYC), a major sister in the art history realm, and everybody respected her. Her art history talks were fascinating. She would talk real fast and have all these pictures and slides, and give you information that you didn’t know existed.

SW: In your 2012 interview with the Never the Same project, you said that "Black art needed to record, identify, and direct." What of Black life have you been documenting through your art during the pandemic and uprisings?

ATC: Mainly I’ve been doing mural work with friends or on my own, and really for the last four or five years. One of the things that is occurring is the move to do more community involvement; there’s more contact where artists and community work together. The artists leave, but the community can tell family members about the space. Every time I pass a space that I took my grandkids to paint, they feel good about themselves and that’s empowering and that’s what I’m liking about the projects I’m doing. My whole thing is we’re Black and we’re about our own self-determination. Those opportunities to show people how you can empower themselves are useful.

Murals are the medium. Back in the ’60s, people like AfriCOBRA, their drive or passion was to get the community more conscious of art. Murals were a way to share your art with the community. They didn’t have to pay for it. It became a cultural point to focus on or learn or understand. AfriCOBRA’s concept of making affordable art was about that, too. So, they produced posters and prints and sold for $55 on high-level serigraph paper, so it was part of a limited-edition piece of artwork that more people could afford than not, and that’s what I think created a vibrant art and collecting community.

Murals are like making sacred places. Back while the Wall of Respect was happening, the community loved it. Gang members protected the space. We artists left paint and materials out every night and nobody messed with it. It became a sacred space. Haki and Margaret, and Gwen Brooks and musicians and spoken word performers and writers started having programming out there. [Murals] can be like stained glass windows in a community—something beautiful, but sacred to that neighborhood that they want to see stay good and neat and pretty.

SW: Can you talk about the bridge between the elder generation of Black artists in Chicago, who honed their artistic perspectives in the shadow of the political and social uprisings of the 1960s and ’70s, and the post-Millennial generation of Chicago-based artists capturing Black life now? What are the elements that have allowed those intergenerational connections to flourish or severed those bonds?

ATC: One thing I was thinking about with this question is when I was working with the Sutherland Community Arts Initiative and the African American Arts Alliance, we worked to develop a mentoring program to bring in younger people interested in arts management, exhibitions, and being artists. We drew up a comprehensive guide that looked at musicians, tech folks, writers, and one of the biggest problems was that you had to have an audience, a means to get to the kids. We did a cursory outreach through the African American Arts Alliance membership to have them commit to colleges and universities to do outreach. It is important to have events that bring younger people together with older people. They’ll enjoy it, but not see it as an opportunity to do something together. Our brainstorm was to recruit a number of older artists from various Black arts institutions, and then try and stage an event that would invite the youth to come join us and do something. Back then we did a couple of things but we never got a big crowd, maybe two to three students. Two to three, that’s where you start anyway, but you also have to have the venue location.

ATC: Mainly I’ve been doing mural work with friends or on my own, and really for the last four or five years. One of the things that is occurring is the move to do more community involvement; there’s more contact where artists and community work together. The artists leave, but the community can tell family members about the space. Every time I pass a space that I took my grandkids to paint, they feel good about themselves and that’s empowering and that’s what I’m liking about the projects I’m doing. My whole thing is we’re Black and we’re about our own self-determination. Those opportunities to show people how you can empower themselves are useful.

Murals are the medium. Back in the ’60s, people like AfriCOBRA, their drive or passion was to get the community more conscious of art. Murals were a way to share your art with the community. They didn’t have to pay for it. It became a cultural point to focus on or learn or understand. AfriCOBRA’s concept of making affordable art was about that, too. So, they produced posters and prints and sold for $55 on high-level serigraph paper, so it was part of a limited-edition piece of artwork that more people could afford than not, and that’s what I think created a vibrant art and collecting community.

Murals are like making sacred places. Back while the Wall of Respect was happening, the community loved it. Gang members protected the space. We artists left paint and materials out every night and nobody messed with it. It became a sacred space. Haki and Margaret, and Gwen Brooks and musicians and spoken word performers and writers started having programming out there. [Murals] can be like stained glass windows in a community—something beautiful, but sacred to that neighborhood that they want to see stay good and neat and pretty.

SW: Can you talk about the bridge between the elder generation of Black artists in Chicago, who honed their artistic perspectives in the shadow of the political and social uprisings of the 1960s and ’70s, and the post-Millennial generation of Chicago-based artists capturing Black life now? What are the elements that have allowed those intergenerational connections to flourish or severed those bonds?

ATC: One thing I was thinking about with this question is when I was working with the Sutherland Community Arts Initiative and the African American Arts Alliance, we worked to develop a mentoring program to bring in younger people interested in arts management, exhibitions, and being artists. We drew up a comprehensive guide that looked at musicians, tech folks, writers, and one of the biggest problems was that you had to have an audience, a means to get to the kids. We did a cursory outreach through the African American Arts Alliance membership to have them commit to colleges and universities to do outreach. It is important to have events that bring younger people together with older people. They’ll enjoy it, but not see it as an opportunity to do something together. Our brainstorm was to recruit a number of older artists from various Black arts institutions, and then try and stage an event that would invite the youth to come join us and do something. Back then we did a couple of things but we never got a big crowd, maybe two to three students. Two to three, that’s where you start anyway, but you also have to have the venue location.

SW: The Sapphire and Crystals collective—of which you are an original member—carved out a necessary space for Black women artists in Chicago to share their artistic POV and produce their own shows. I imagine the institutional memory you all hold about this city and how you share and weave those narratives into your work could launch 1,000 shows. What are the narratives about Black people and Black women especially that you want to see endure over time?

ATC: Sapphire and Crystals is between 30 and 35 years old. Marva Jolly and Felicia Grant Preston were in a group together called Mud Peoples, where Marva worked with artists who worked with clay. They had a discussion one day about the plight of women artists and came up with the idea to bring women together to discuss what’s happening with them and not getting exhibitions. It’s hard for women artists to be seen seriously, back in the 1960s and ’70s, let alone get exhibitions, let alone be a Black woman. That was their goal. We discussed that we wanted to start being proactive about getting our art out instead of waiting to be invited to be part of a show. Just being one little cog, and that’s how we started. In that one afternoon, we shaped our goals. We said we wanted to invite women to join us, create exhibitions, and create catalogs that women could take to other spaces to market our work. We wanted kujichagulia—self-determination about our art. And then we’d aggressively look for venues that would show women’s exhibitions.

We wanted to not have our exhibitions in February because everyone looks for that kind of work in February. We did September or October—Marva’s birthday was October. We’d have artists’ statements and have our people proofread our writing. We all tried to take [on] different tasks. We said we’d put a little money in the till from each of us to cover the cost of printing the catalog and sell that catalog at each event to be seed money for the next. We instituted a silent auction which hopefully would encourage people to collect our work. Keeping the opening bids to $150. That’s how it developed for the first 10 years, we had a show every year. White women at the same time were asserting themselves in the same way so we found galleries on the North Side, like Artemisia, ARC, and Women Made Gallery. These helped encourage us. Some of our artists would work in universities, so we’d called upon them to see if we could get shows on campuses, like at Illinois Wesleyan, Northeastern University, or the Illinois Arts Center. As we grew in reputation, we could be relied upon to consistently put up a good show and venues were happy to have us. We had good editorial control and good curatorial control. That was how we got started. Then we started thinking about installations in our shows. We’d lost members from death and wanted to honor them. In recent history, there’s always been an in memoriam installation, with a silent auction or something in line with the exhibition theme, and then an installation where we would make an altar for our sisters who had passed away. Then we also try to aggressively recruit younger artists we know and invite them to participate.

ATC: Sapphire and Crystals is between 30 and 35 years old. Marva Jolly and Felicia Grant Preston were in a group together called Mud Peoples, where Marva worked with artists who worked with clay. They had a discussion one day about the plight of women artists and came up with the idea to bring women together to discuss what’s happening with them and not getting exhibitions. It’s hard for women artists to be seen seriously, back in the 1960s and ’70s, let alone get exhibitions, let alone be a Black woman. That was their goal. We discussed that we wanted to start being proactive about getting our art out instead of waiting to be invited to be part of a show. Just being one little cog, and that’s how we started. In that one afternoon, we shaped our goals. We said we wanted to invite women to join us, create exhibitions, and create catalogs that women could take to other spaces to market our work. We wanted kujichagulia—self-determination about our art. And then we’d aggressively look for venues that would show women’s exhibitions.

We wanted to not have our exhibitions in February because everyone looks for that kind of work in February. We did September or October—Marva’s birthday was October. We’d have artists’ statements and have our people proofread our writing. We all tried to take [on] different tasks. We said we’d put a little money in the till from each of us to cover the cost of printing the catalog and sell that catalog at each event to be seed money for the next. We instituted a silent auction which hopefully would encourage people to collect our work. Keeping the opening bids to $150. That’s how it developed for the first 10 years, we had a show every year. White women at the same time were asserting themselves in the same way so we found galleries on the North Side, like Artemisia, ARC, and Women Made Gallery. These helped encourage us. Some of our artists would work in universities, so we’d called upon them to see if we could get shows on campuses, like at Illinois Wesleyan, Northeastern University, or the Illinois Arts Center. As we grew in reputation, we could be relied upon to consistently put up a good show and venues were happy to have us. We had good editorial control and good curatorial control. That was how we got started. Then we started thinking about installations in our shows. We’d lost members from death and wanted to honor them. In recent history, there’s always been an in memoriam installation, with a silent auction or something in line with the exhibition theme, and then an installation where we would make an altar for our sisters who had passed away. Then we also try to aggressively recruit younger artists we know and invite them to participate.

Parenting and other jobs definitely made things challenging for some of our members. In some cases, the work wasn’t what we needed it to be, because we were trying to make certain that we had a certain level of professionalism. The work had to come in ready to be hung. Presentation is part of the art, not just the subject matter. It needs to look well together, as well as being well-done and a certain technical proficiency should be shown. People had to hold down other jobs, or couldn’t meet deadlines for grants or submissions because of your other life. That happens a lot to women. We discussed that early on. Very few of us are full-time artists. Most of us are supporting families. I’m a night person, that’s when I would work. When I was older, I got a studio a few nights a week and would work there.

What new are we thinking about with the art? We thought about how mothers have to survive with mother-wit. I think nowadays, we need to have some survival techniques. We have to have ways to get through things. I’m thinking about young women who are at times not able to see their own potential or recognize how to get through bad relationships, struggles with jobs, self-worth, and these are things that I’d like to see addressed for women, as well as for our community. We need reparations for our cultural institutions and identifying just how we can build endowments to take our institutions into perpetuity. The reason many of our institutions have failed or are struggling is that we just get little bits of money. For example, there could be a $1 million pot, but everyone’s getting $5,000 or $10,000. The Museum of Science and Industry or the Art Institute get $250,000 and that’s the norm. Smaller institutions are competing with each other and major institutions get a lion’s share of money off the top.

The whole idea of equity—does this country have this kind of mindset that could do away with privilege? But that’s what needs to be the solution. That you create a means for more people to create equitable lives. Whether you do that because of reparations or you just break down your privileged ways of doing things. Racism needs to be gone. When you have the Symphony and Art Institute and major museums getting millions and already have endowments and Muntu has to raise $2 million every year just to meet payroll, and they didn’t have a building or were unable to house, that’s not equitable.

What new are we thinking about with the art? We thought about how mothers have to survive with mother-wit. I think nowadays, we need to have some survival techniques. We have to have ways to get through things. I’m thinking about young women who are at times not able to see their own potential or recognize how to get through bad relationships, struggles with jobs, self-worth, and these are things that I’d like to see addressed for women, as well as for our community. We need reparations for our cultural institutions and identifying just how we can build endowments to take our institutions into perpetuity. The reason many of our institutions have failed or are struggling is that we just get little bits of money. For example, there could be a $1 million pot, but everyone’s getting $5,000 or $10,000. The Museum of Science and Industry or the Art Institute get $250,000 and that’s the norm. Smaller institutions are competing with each other and major institutions get a lion’s share of money off the top.

The whole idea of equity—does this country have this kind of mindset that could do away with privilege? But that’s what needs to be the solution. That you create a means for more people to create equitable lives. Whether you do that because of reparations or you just break down your privileged ways of doing things. Racism needs to be gone. When you have the Symphony and Art Institute and major museums getting millions and already have endowments and Muntu has to raise $2 million every year just to meet payroll, and they didn’t have a building or were unable to house, that’s not equitable.

SW: We’ve focused on loss. But what are existing Chicago spaces that have inspired you in the past, or now, to create?

ATC: The Quarry in South Shore. The art centers, and some places and spaces in Bronzeville. I ride my bike a lot. When the Jazz Festival was downtown, I would ride my bike down to Millennium Park and bring a little sketchbook. I’ll take pictures of musicians while they’re performing. Instead of getting on a trolley, I’ll ride my bike to different venues, if they have something at Rockefeller Chapel or something in the Midway and just lay out in the sun. Or going to hear some music to be inspired and encouraged. Artists are in our heads a lot. I’m not at all inspired by the Trump administration. I think art needs to be transformative. I don’t want to take up an idea that’s grounded in a negative space. I want to put out a positive idea to be transformative against all the negative stuff we see.

I did a couple of pieces on the sisters kidnapped by Boko Haram, because I wanted to try and shine a light on that. Or I think about Candace Hunter, she’s brilliant in terms of coming up with these wonderful installations or series, like the “Hooded Truth” series, or “Women in Water” works, where she’s shining a light on the fact that women all over the world have to carry water, and maintain their rights to, and what’s going on with that. Those kinds of things inspire me. Seeing my colleagues doing projects, working with other people on the murals. That’s what feeds me. And doing collaborations or participating in things that are valuable for people to think about. ︎

ATC: The Quarry in South Shore. The art centers, and some places and spaces in Bronzeville. I ride my bike a lot. When the Jazz Festival was downtown, I would ride my bike down to Millennium Park and bring a little sketchbook. I’ll take pictures of musicians while they’re performing. Instead of getting on a trolley, I’ll ride my bike to different venues, if they have something at Rockefeller Chapel or something in the Midway and just lay out in the sun. Or going to hear some music to be inspired and encouraged. Artists are in our heads a lot. I’m not at all inspired by the Trump administration. I think art needs to be transformative. I don’t want to take up an idea that’s grounded in a negative space. I want to put out a positive idea to be transformative against all the negative stuff we see.

I did a couple of pieces on the sisters kidnapped by Boko Haram, because I wanted to try and shine a light on that. Or I think about Candace Hunter, she’s brilliant in terms of coming up with these wonderful installations or series, like the “Hooded Truth” series, or “Women in Water” works, where she’s shining a light on the fact that women all over the world have to carry water, and maintain their rights to, and what’s going on with that. Those kinds of things inspire me. Seeing my colleagues doing projects, working with other people on the murals. That’s what feeds me. And doing collaborations or participating in things that are valuable for people to think about. ︎

Stacie Williams (she/her) is director of the Center for Digital Scholarship at the University of Chicago Libraries, and a member of the Chicago-based Blackivist archivist collective, which works with individuals and organizations to preserve Black Chicagoland memory and culture. Her work is centered on sustainability of digital and web-based knowledge sources and equitable labor practices in cultural heritage professions. Williams was previously an advisory archivist for A People’s Archive of Police Violence in Cleveland, a 2015 oral history project that documented people’s experiences with police violence and harassment in the Cleveland metropolitan area, and a former journalist for more than 10 years. Her first book, Bizarro Worlds (Fiction Advocate), a bibliomemoir about race and gentrification, was released in 2018.