Ancestor and Descendant: A Conversation with Steven G. Fullwood

Interview by Steven D. Booth

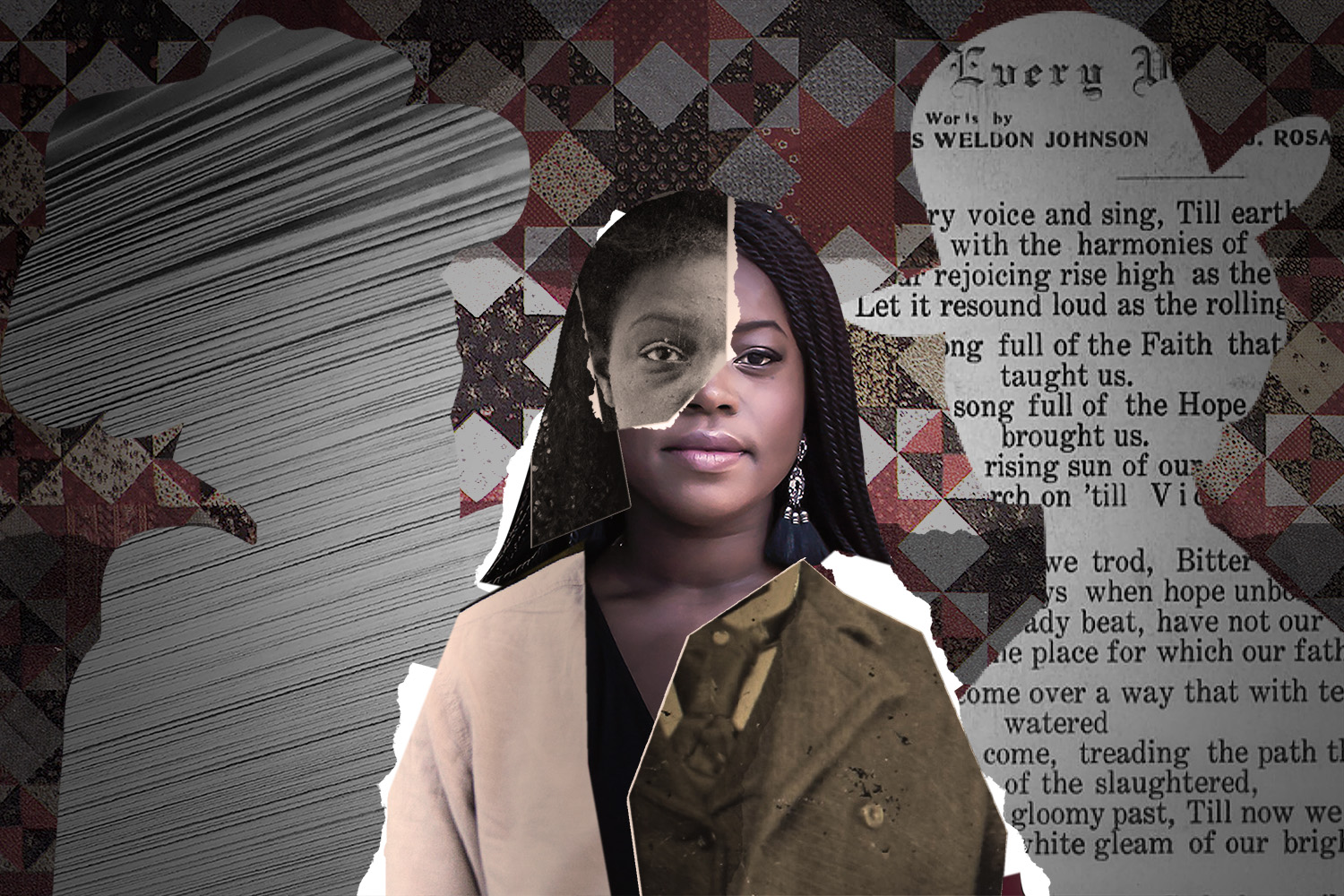

Steven G. Fullwood (he/his) is an archivist, documentarian, and writer. His published works include Black Gay Genius (co-edited with Charles Stephens, 2014), To Be Left with the Body (co-edited with Cheryl Clarke, 2008) and Carry the Word: A Bibliography of Black LGBTQ Books (co-edited with Lisa C. Moore, 2007). He is the former assistant curator of the Manuscripts, Archives & Rare Books Division at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. In 1998, he founded the In the Life Archive (ITLA) to aid in the preservation of materials produced by LGBTQ people of African descent. Fullwood is the co-founder of The Nomadic Archivists Project, an initiative that partners with organizations, institutions, and individuals to establish, preserve, and enhance collections that explore the African Diasporic experience. In 2005, Fullwood was honored with a New York Times Librarian Award.

Steven D. Booth: Tell us about your background (i.e., who you are, where you work, and what you do).

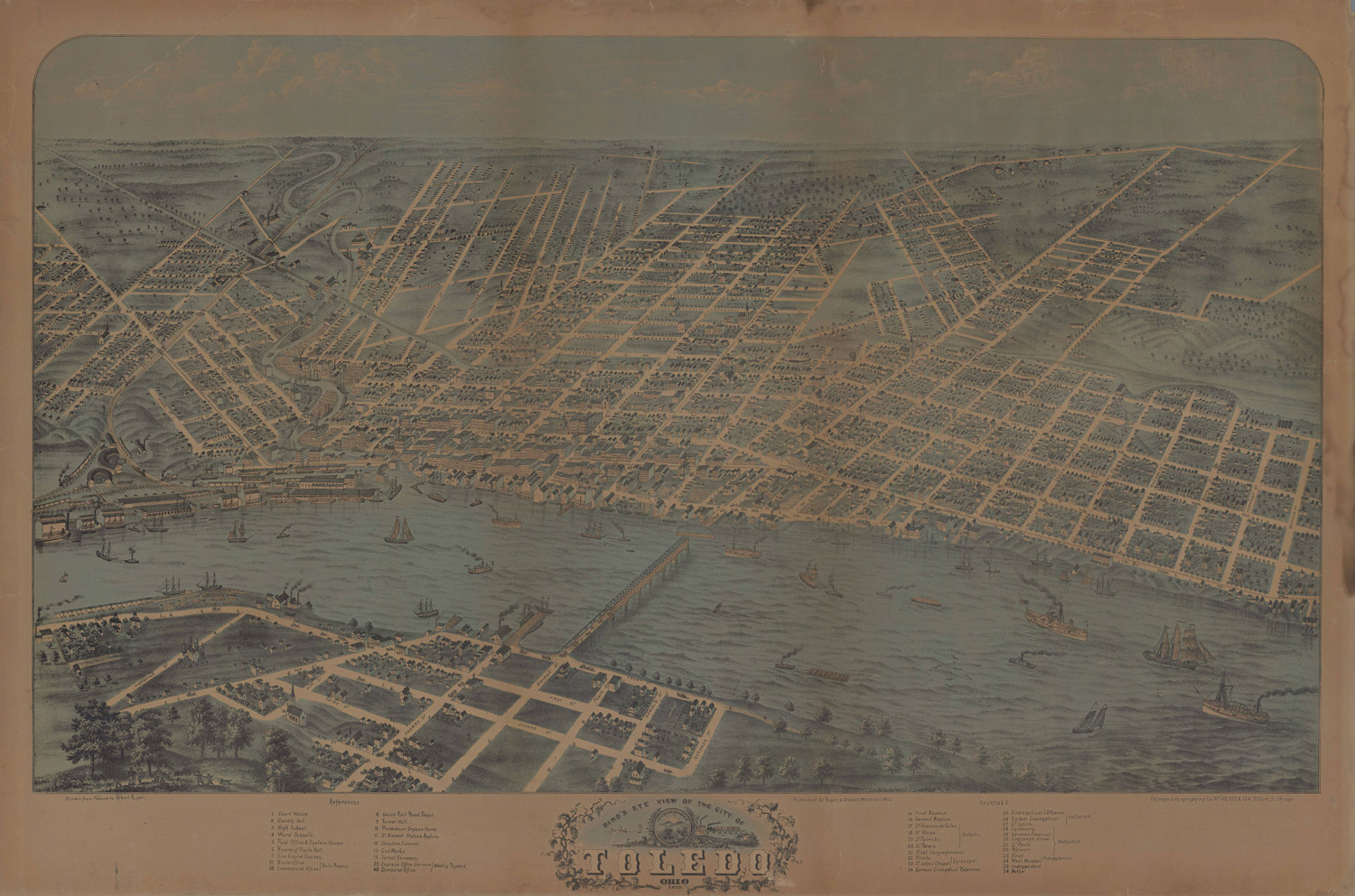

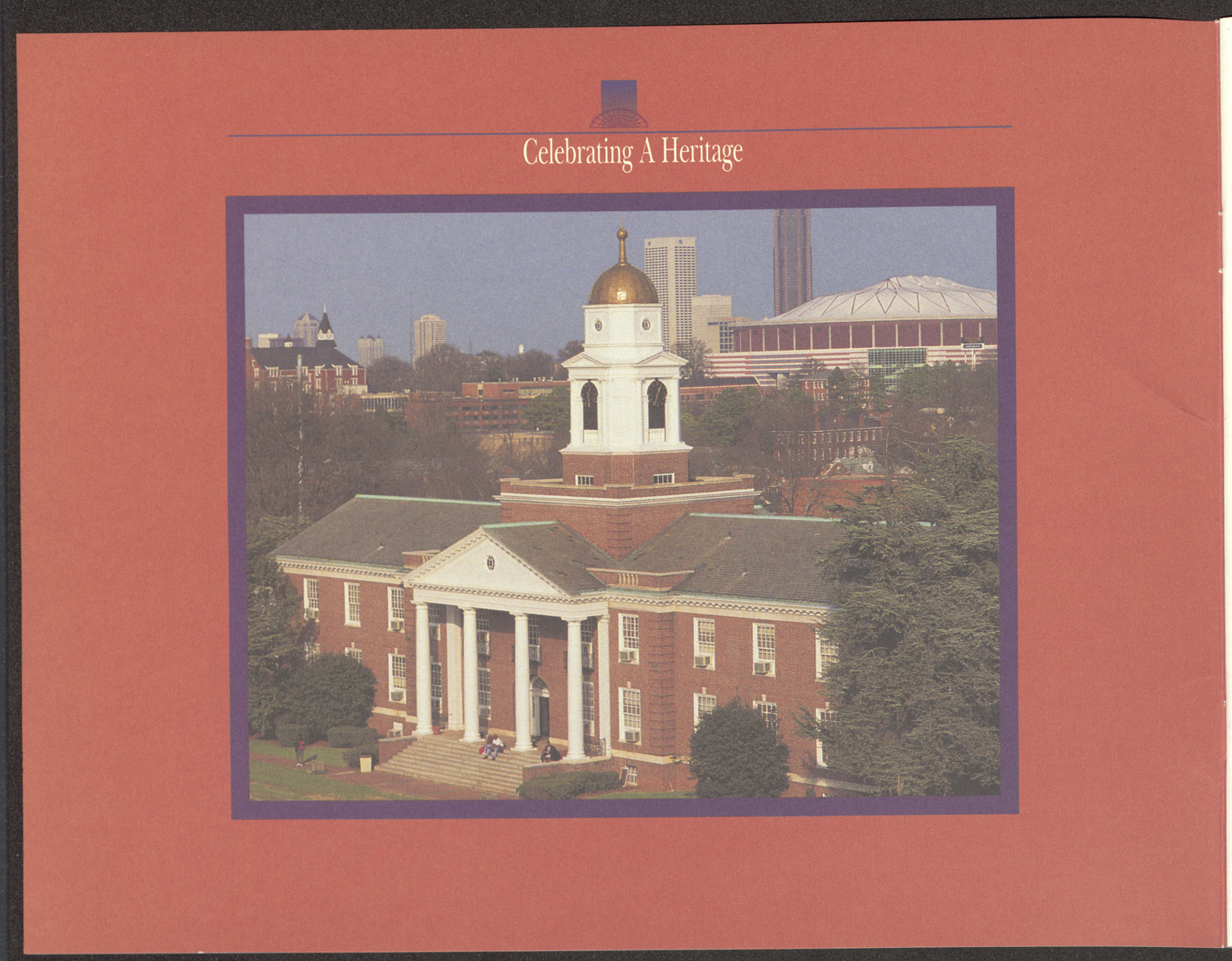

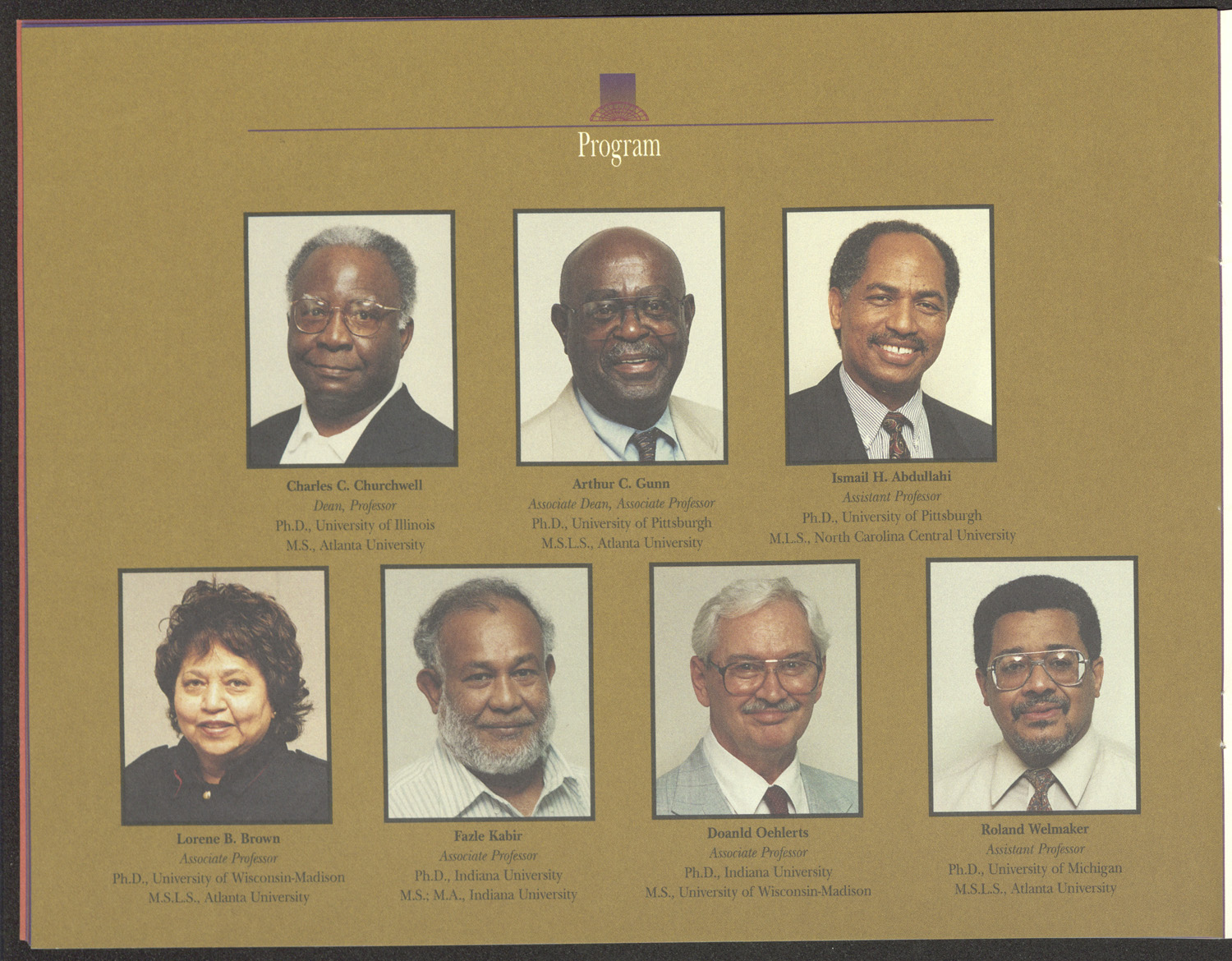

Steven G. Fullwood: I was born and raised on the southside of Toledo, Ohio in a white-flight neighborhood called Kuschwantz1, which was one of two Polish settlements in the early 20th Century. My parents, a Southern father and a Midwesterner mother, are descendants of farmers, preachers, hustlers, domestics, and handymen. My dad sang gospel in a short-lived trio called the Horns of Zion, and my mother was a reader. She would read anything if it caught her attention. Mom loved romance and horror books. I grew up in a musical and literary household with lots of television. I’m the third of five children, the pesky middle kid. And I tried to be a singer and musician, but I’m no good at either so I gave it up. I hold two degrees, a BA in English and Communications from the University of Toledo, and an MLIS from Clark Atlanta University. For over 19 years, I was an archivist, associate curator, and finally assistant curator at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library.

What a privilege it was to work with the best archivists, curators, staff, pages, etc., ever. The Schomburg Center taught me virtually everything I needed to know about Black archives, their importance, context, and politics here and globally. I left the Schomburg in 2017 to learn how to make films and be an independent archivist. At the end of 2017, Miranda Mims approached me to see if I wanted to collaborate with her on a community project, and that’s how the Nomadic Archivists Project was born. Since then, we’ve developed a Black podcast archive, co-host In the Telling, a Black family podcast, and awarded our first scholarship to a student studying archives. I love coalition building with Black and Brown communities about the different ways we archivists and other memory workers can help them preserve our stories.

SDB: Tell us something that most people don't know about your work but that is crucial to do the work.

SGF: Archives really chose me, not the other way around. And I think those who feel compelled to do this kind [of] work would agree with me. It’s infectious because it feeds you in ways that can surprise you. It’s a lens from which you can better understand not just history, but people, culture and, for me, it transcends the boundaries of physical representations of memory.

Processing a collection is a form of storytelling in and of itself, providing access for researchers and simultaneously planting seeds for stories wanting to be born. It’s a generative practice, very fluid and inspiring and inherently political. Whose stories, and where are they archived? What’s crucial to doing archival work is knowing that you’re assisting in not just putting down the history, but you are a conduit for a certain kind of energy transfer. Archivists can be great storytellers and fine ambassadors for the field itself because [they are] able to make archives accessible and relatable. By contrast, archivists can also either help or hurt a cause based on what they collect and how they present collections.

I think I was born to be an archivist. As a kid, I collected and arranged my comics. Created lists of those comics. In my teens I began to write stories and journal. [I] took photographs of my neighborhood and developed an interest in genealogy. In 1989, I interviewed my mother for a book project on Black women in Toledo (never finished it, but just had the cassette tapes digitized). A decade later, I was at the Schomburg being taught to be responsible for the stories of our communities, diasporically, which was like being in college for nearly two decades. It’s a responsibility that one never quite learns completely. I see it more as a practice.

The African diaspora was revealed to me in a way that I couldn’t have learned any other way, and not just through cultural evidence filling the Schomburg’s shelves, but through the people who worked there, firsthand. There was nothing like being with a group of culture keepers, immigrants, activists, thinkers, etc., who did great work and often had outside interests in performing music, building community organizations, being active in social and political demonstrations, etc. This was the world in which I was nurtured and offered a space to make a contribution, specifically in the case of and for the Black LGBTQ community.

Steven D. Booth: Tell us about your background (i.e., who you are, where you work, and what you do).

Steven G. Fullwood: I was born and raised on the southside of Toledo, Ohio in a white-flight neighborhood called Kuschwantz1, which was one of two Polish settlements in the early 20th Century. My parents, a Southern father and a Midwesterner mother, are descendants of farmers, preachers, hustlers, domestics, and handymen. My dad sang gospel in a short-lived trio called the Horns of Zion, and my mother was a reader. She would read anything if it caught her attention. Mom loved romance and horror books. I grew up in a musical and literary household with lots of television. I’m the third of five children, the pesky middle kid. And I tried to be a singer and musician, but I’m no good at either so I gave it up. I hold two degrees, a BA in English and Communications from the University of Toledo, and an MLIS from Clark Atlanta University. For over 19 years, I was an archivist, associate curator, and finally assistant curator at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library.

What a privilege it was to work with the best archivists, curators, staff, pages, etc., ever. The Schomburg Center taught me virtually everything I needed to know about Black archives, their importance, context, and politics here and globally. I left the Schomburg in 2017 to learn how to make films and be an independent archivist. At the end of 2017, Miranda Mims approached me to see if I wanted to collaborate with her on a community project, and that’s how the Nomadic Archivists Project was born. Since then, we’ve developed a Black podcast archive, co-host In the Telling, a Black family podcast, and awarded our first scholarship to a student studying archives. I love coalition building with Black and Brown communities about the different ways we archivists and other memory workers can help them preserve our stories.

SDB: Tell us something that most people don't know about your work but that is crucial to do the work.

SGF: Archives really chose me, not the other way around. And I think those who feel compelled to do this kind [of] work would agree with me. It’s infectious because it feeds you in ways that can surprise you. It’s a lens from which you can better understand not just history, but people, culture and, for me, it transcends the boundaries of physical representations of memory.

Processing a collection is a form of storytelling in and of itself, providing access for researchers and simultaneously planting seeds for stories wanting to be born. It’s a generative practice, very fluid and inspiring and inherently political. Whose stories, and where are they archived? What’s crucial to doing archival work is knowing that you’re assisting in not just putting down the history, but you are a conduit for a certain kind of energy transfer. Archivists can be great storytellers and fine ambassadors for the field itself because [they are] able to make archives accessible and relatable. By contrast, archivists can also either help or hurt a cause based on what they collect and how they present collections.

I think I was born to be an archivist. As a kid, I collected and arranged my comics. Created lists of those comics. In my teens I began to write stories and journal. [I] took photographs of my neighborhood and developed an interest in genealogy. In 1989, I interviewed my mother for a book project on Black women in Toledo (never finished it, but just had the cassette tapes digitized). A decade later, I was at the Schomburg being taught to be responsible for the stories of our communities, diasporically, which was like being in college for nearly two decades. It’s a responsibility that one never quite learns completely. I see it more as a practice.

The African diaspora was revealed to me in a way that I couldn’t have learned any other way, and not just through cultural evidence filling the Schomburg’s shelves, but through the people who worked there, firsthand. There was nothing like being with a group of culture keepers, immigrants, activists, thinkers, etc., who did great work and often had outside interests in performing music, building community organizations, being active in social and political demonstrations, etc. This was the world in which I was nurtured and offered a space to make a contribution, specifically in the case of and for the Black LGBTQ community.

SDB: In your work at the Schomburg as a curator, how did you interact with the concept of documenting the loss and/or capture of Black cultural heritage collections, sites, memory, etc.? How much of it was about either preventative capture or post-memorial about loss?

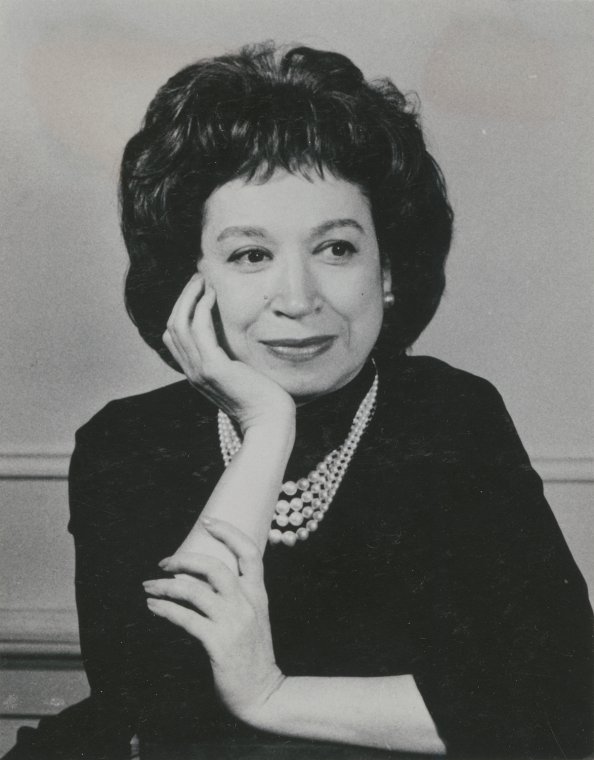

SGF: Just a few years shy of a century, the Schomburg built a solid reputation as a repository for Black memory. Led by Black Puerto Rican bibliophile and scholar Arthur Schomburg, curators and directors including Lawrence Reddick, Jean Blackwell Hutson, Howard Dodson, Diana Lachatanere, Mary Yearwood, James Briggs Murray, Genette McLaurin, Victor Smythe, and Tammi Lawson, as well as countless librarians, archivists, and support staff, the Center could assume a privileged position as a leader in the world’s community dedicated to saving Black global culture.

Seriously considering these questions, I realize just how embedded in Schomburg’s ethos were these daily concerns that shaped collection development, how collections were processed, what kinds of grants we received, coalition work to help preserve the African Burial Ground, analog and digital exhibitions and collection presentations, and hundreds of free public programs over the years that disrupted false narratives about Black life and accomplishment and fed new perspectives. Celebrating Black history and culture isn’t simply to counter racism, it was/is to freedom fight as an imperative.

A good example of preemptive capture (and to be honest, I need and want a better term that feels less constrictive and violent than capture2), is a project I founded/directed called the In the Life Archive (ITLA), formerly known as the Black Gay & Lesbian Archive. It’s important to note several things about the project. First and foremost, the ITLA was built by the Black LGBTQ community. I just happened to be in the right place at the right time. From 1999 to the present, Black queer folks have donated their papers, supported programming, and given money to see this project happen. Although I reached out to individuals I thought might be interested in the project, I was also contacted by people interested in donating their collections. Brad Johnson, a Black gay Philadelphia poet active in the 1980s and 1990s reached out to me through his social worker. In 2012, he was on his deathbed and was certain that neither his family nor his alma mater Yale would be interested in his papers. Of course, I was interested and shortly after we packed up the collection, Brad had passed. I bring up Brad as an example of how the culture has been slowly changing. Now, a Black LGBTQ person might consider that hers/his/their archive might be historically significant. And that there are places to contact that might be interested in archiving their legacies.

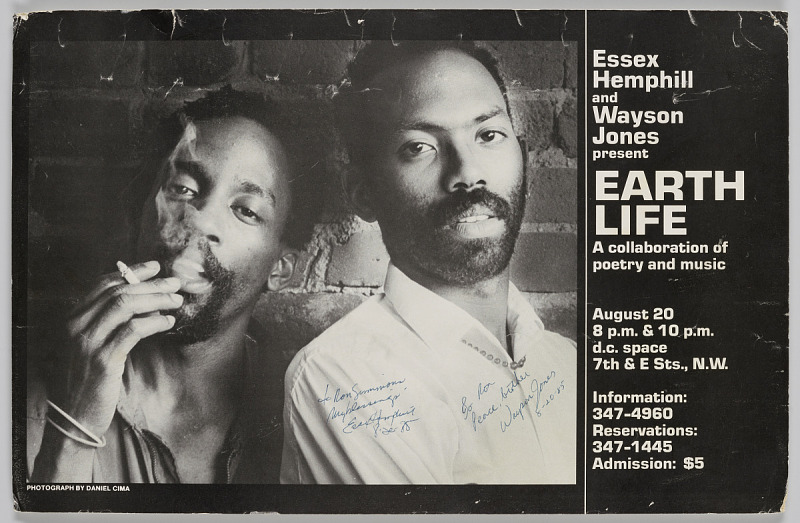

Right now, I see that collecting Black LGBTQ history and culture has come to the attention of the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC), historians, and various scholars. This is wonderful and necessary and long overdue. On the one hand, Black culture has always been popular, [but] mainstream institutions weren’t collecting Black archives with the exception of a few institutions like the Moorland-Spingarn Center, Schomburg Center, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History, and a few others. Black archives now have more currency. Collections are being sought after by the Ivys and public institutions. Part of it is scholarly interest has increased due to academia’s interest in historical events that happened 40-50 years ago. And [also due to] the professors who taught Audre Lorde, Barbara Smith, Essex Hemphill, Joseph Beam, and others for decades. Black LGBTQ culture and history often intersects with women’s history, Black Power and Black Arts history, diasporic histories, and HIV/AIDS culture and history, as well as literature, film, and music. Black LGBTQ has a lot to tell us about cultural production, the church, the family, what HIV/AIDS activism meant during a pandemic, and human rights struggles.

I estimate we’ve lost more collections than we have been able to archive due to the ravages of HIV/AIDS, as well as the lack of connections with archives and libraries. I’m still working out the numbers. But because there are more archives doing this work, the awareness about Black LGBTQ archives is becoming more common. For example, NMAAHC has acquired photographs from the late Ron Simmons, a pioneering activist and figure in Black LGBTQ history. Although there is a paper collection of Ron’s at the Schomburg, his audio/visual collection might have been lost had the museum not contacted him. Frankly, Ron was a Washington D.C. legend. I’m pleased that NMAAHC knew this and was proactive in collecting Ron’s work.

SGF: Just a few years shy of a century, the Schomburg built a solid reputation as a repository for Black memory. Led by Black Puerto Rican bibliophile and scholar Arthur Schomburg, curators and directors including Lawrence Reddick, Jean Blackwell Hutson, Howard Dodson, Diana Lachatanere, Mary Yearwood, James Briggs Murray, Genette McLaurin, Victor Smythe, and Tammi Lawson, as well as countless librarians, archivists, and support staff, the Center could assume a privileged position as a leader in the world’s community dedicated to saving Black global culture.

Seriously considering these questions, I realize just how embedded in Schomburg’s ethos were these daily concerns that shaped collection development, how collections were processed, what kinds of grants we received, coalition work to help preserve the African Burial Ground, analog and digital exhibitions and collection presentations, and hundreds of free public programs over the years that disrupted false narratives about Black life and accomplishment and fed new perspectives. Celebrating Black history and culture isn’t simply to counter racism, it was/is to freedom fight as an imperative.

A good example of preemptive capture (and to be honest, I need and want a better term that feels less constrictive and violent than capture2), is a project I founded/directed called the In the Life Archive (ITLA), formerly known as the Black Gay & Lesbian Archive. It’s important to note several things about the project. First and foremost, the ITLA was built by the Black LGBTQ community. I just happened to be in the right place at the right time. From 1999 to the present, Black queer folks have donated their papers, supported programming, and given money to see this project happen. Although I reached out to individuals I thought might be interested in the project, I was also contacted by people interested in donating their collections. Brad Johnson, a Black gay Philadelphia poet active in the 1980s and 1990s reached out to me through his social worker. In 2012, he was on his deathbed and was certain that neither his family nor his alma mater Yale would be interested in his papers. Of course, I was interested and shortly after we packed up the collection, Brad had passed. I bring up Brad as an example of how the culture has been slowly changing. Now, a Black LGBTQ person might consider that hers/his/their archive might be historically significant. And that there are places to contact that might be interested in archiving their legacies.

Right now, I see that collecting Black LGBTQ history and culture has come to the attention of the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC), historians, and various scholars. This is wonderful and necessary and long overdue. On the one hand, Black culture has always been popular, [but] mainstream institutions weren’t collecting Black archives with the exception of a few institutions like the Moorland-Spingarn Center, Schomburg Center, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History, and a few others. Black archives now have more currency. Collections are being sought after by the Ivys and public institutions. Part of it is scholarly interest has increased due to academia’s interest in historical events that happened 40-50 years ago. And [also due to] the professors who taught Audre Lorde, Barbara Smith, Essex Hemphill, Joseph Beam, and others for decades. Black LGBTQ culture and history often intersects with women’s history, Black Power and Black Arts history, diasporic histories, and HIV/AIDS culture and history, as well as literature, film, and music. Black LGBTQ has a lot to tell us about cultural production, the church, the family, what HIV/AIDS activism meant during a pandemic, and human rights struggles.

I estimate we’ve lost more collections than we have been able to archive due to the ravages of HIV/AIDS, as well as the lack of connections with archives and libraries. I’m still working out the numbers. But because there are more archives doing this work, the awareness about Black LGBTQ archives is becoming more common. For example, NMAAHC has acquired photographs from the late Ron Simmons, a pioneering activist and figure in Black LGBTQ history. Although there is a paper collection of Ron’s at the Schomburg, his audio/visual collection might have been lost had the museum not contacted him. Frankly, Ron was a Washington D.C. legend. I’m pleased that NMAAHC knew this and was proactive in collecting Ron’s work.

SDB: Throughout your career, you've worked to acquire the materials of some notable and lesser-known Black individuals, families, and organizations. Within the past decade, there's been an uptick in the number of Black collections that are either being shopped around, purchased, or auctioned. What are your thoughts on the commodification of Black cultural heritage collections? Do you consider this practice harmful? If so, why?

SGF: The commodification of Black archival collections is a result of the predatory capitalism we practice today in the U.S. It has a profound, disruptive effect on collecting practices. Larger institutions with larger budgets want to matter in this current context and frankly are taking advantage of it. Why? Because predatory capitalism respects no one, and certainly not its cultural institutions as instruments of a free culture. They are or become spoils of the empire. And as we non-Black people continue to rage against [it] in the streets, academia, in our communities, and other cultural expressions, we know that it is the storyteller that matters and who controls the story.

Black culture sells. Institutions with smaller budgets cannot compete in the marketplace, absolutely. What’s fucked up about that the collection in question might be better cared for at a smaller institution. At one point in history, collections were donated to archives. I still think that’s true, in a way. I want it to be clear that I’m completely in favor of Black people being paid for their collections, but that’s also how brand-name collections end up in college and universities as the only one of its kind culturally or racially. In many ways, it’s out of context. Let me explain what I mean by that. Cultural institutions that have one or two Black, queer, or women’s collections can’t adequately reveal the nuances or particularities of said individual, organization, or institution. Those collections end up becoming unique or special, and they are, but in an institution filled with similar collections and other kinds of contextual materials, they become more than special; they become legible in profound ways. James Baldwin, Lorraine Hansberry, Julian Mayfield, Alice Childress, Ossie Davis, and Ruby Dee, among others, were all part of the Black Left in the 1950s and 1960s and are at the Schomburg Center. Reading their scripts, letters, and considering [how] their creative lives and activist works resonate with each other, offer powerful contexts that make less sense in larger, white institutions where they may have one or two Black collections.

SGF: The commodification of Black archival collections is a result of the predatory capitalism we practice today in the U.S. It has a profound, disruptive effect on collecting practices. Larger institutions with larger budgets want to matter in this current context and frankly are taking advantage of it. Why? Because predatory capitalism respects no one, and certainly not its cultural institutions as instruments of a free culture. They are or become spoils of the empire. And as we non-Black people continue to rage against [it] in the streets, academia, in our communities, and other cultural expressions, we know that it is the storyteller that matters and who controls the story.

Black culture sells. Institutions with smaller budgets cannot compete in the marketplace, absolutely. What’s fucked up about that the collection in question might be better cared for at a smaller institution. At one point in history, collections were donated to archives. I still think that’s true, in a way. I want it to be clear that I’m completely in favor of Black people being paid for their collections, but that’s also how brand-name collections end up in college and universities as the only one of its kind culturally or racially. In many ways, it’s out of context. Let me explain what I mean by that. Cultural institutions that have one or two Black, queer, or women’s collections can’t adequately reveal the nuances or particularities of said individual, organization, or institution. Those collections end up becoming unique or special, and they are, but in an institution filled with similar collections and other kinds of contextual materials, they become more than special; they become legible in profound ways. James Baldwin, Lorraine Hansberry, Julian Mayfield, Alice Childress, Ossie Davis, and Ruby Dee, among others, were all part of the Black Left in the 1950s and 1960s and are at the Schomburg Center. Reading their scripts, letters, and considering [how] their creative lives and activist works resonate with each other, offer powerful contexts that make less sense in larger, white institutions where they may have one or two Black collections.

SDB: In thinking about your experience as a curator, archivist, and documentarian, what do you consider to be the biggest threats to keeping and sustaining Black cultural heritage institutions?

SGF: No money, mercurial attitudes of funding institutions, and lack of imagination. Right now, Black and other archives that weren’t initially seen by white mainstream institutions as worthy of collection are currently in vogue. Maybe tomorrow they won’t be. Obviously, it wouldn’t be because of their inherent value, research, or otherwise. For me, it comes down to what the best of what Black institutions can do, which is present the counter narrative and maintain their stances because we know that no matter the political or social moment, our stories matter and need to be preserved, regardless.

While the US is still treating Black people as second-class citizens, if that, there’s no debate among Black people that we matter. But that’s just us and others who support this kind of work. One old narrative currently in circulation is why have these Black institutions? They’re separatist and if we’re trying to solve racism, why do we need them, which is obvious hogwash. Cultural institutions, of all kinds, need room to breathe. This is the history of the US we are only now reckoning with. No one should question their existence. American amnesia is so strong, so insidious that one can’t quite fathom the damage it's done to the development of this country.

SGF: No money, mercurial attitudes of funding institutions, and lack of imagination. Right now, Black and other archives that weren’t initially seen by white mainstream institutions as worthy of collection are currently in vogue. Maybe tomorrow they won’t be. Obviously, it wouldn’t be because of their inherent value, research, or otherwise. For me, it comes down to what the best of what Black institutions can do, which is present the counter narrative and maintain their stances because we know that no matter the political or social moment, our stories matter and need to be preserved, regardless.

While the US is still treating Black people as second-class citizens, if that, there’s no debate among Black people that we matter. But that’s just us and others who support this kind of work. One old narrative currently in circulation is why have these Black institutions? They’re separatist and if we’re trying to solve racism, why do we need them, which is obvious hogwash. Cultural institutions, of all kinds, need room to breathe. This is the history of the US we are only now reckoning with. No one should question their existence. American amnesia is so strong, so insidious that one can’t quite fathom the damage it's done to the development of this country.

SDB: As archivists, we work to preserve the narratives, legacies, and histories of individuals and communities, but rarely do we give ourselves the same consideration. Have you given any thought about your own archive? What do you hope archivists and researchers will learn about you? Name one item that you will include and why?

SGF: Yes, I’ve thought about my own archive, actively so. If you’ve ever worked in an archive, you know about the amazing stories that archivists tell about this person or that collection, much of which never appears in finding aids, bio sketches, or elsewhere. Rescue stories, family stories, surprises in the archive stories, and more. These stories impacted me greatly as an archivist. They offered me something beyond technical expertise. They shaped my vision about the necessity of preserving cultural heritage. Archivists are often completely misunderstood as culture keepers. Most people don’t even know what an archivist does.

I’m trying to encourage other Black archivists to at least [create] oral histories of their lives and to really focus on their careers. The amazing stories of Black archivists shouldn’t die when they die; they have and continue to shape my work as a memory worker. Much of what we consider behind the counter talk (conversations often governed by privacy) could in part be shared with the community to pull back the veil partially on the business of archives and the stories about how collections get to institutions—or not. I’m also organizing my own personal records, analog and digital. I’ve been fortunate to have a career as a writer and publisher and so part of that constitutes my archive, as well as personal records such as correspondence, photographs, family records, etc. I wholeheartedly feel that organizing one’s archive is a unique and generative process. I think you deserve the benefit of your own experience, repeatedly, throughout your life. You are the descendant and ancestor. Your story matters in profoundly moving ways because it is our collective story.

The one item I would include is a draft of a recipe book my dad gave me years ago. The way I’ve expressed my love in the past was to build an art project with a person I love. My dad’s handwriting alone delights me. His recipes are okay, not remarkable, but they’re my dad’s recipes, and so they matter to me and my family. ︎

SGF: Yes, I’ve thought about my own archive, actively so. If you’ve ever worked in an archive, you know about the amazing stories that archivists tell about this person or that collection, much of which never appears in finding aids, bio sketches, or elsewhere. Rescue stories, family stories, surprises in the archive stories, and more. These stories impacted me greatly as an archivist. They offered me something beyond technical expertise. They shaped my vision about the necessity of preserving cultural heritage. Archivists are often completely misunderstood as culture keepers. Most people don’t even know what an archivist does.

I’m trying to encourage other Black archivists to at least [create] oral histories of their lives and to really focus on their careers. The amazing stories of Black archivists shouldn’t die when they die; they have and continue to shape my work as a memory worker. Much of what we consider behind the counter talk (conversations often governed by privacy) could in part be shared with the community to pull back the veil partially on the business of archives and the stories about how collections get to institutions—or not. I’m also organizing my own personal records, analog and digital. I’ve been fortunate to have a career as a writer and publisher and so part of that constitutes my archive, as well as personal records such as correspondence, photographs, family records, etc. I wholeheartedly feel that organizing one’s archive is a unique and generative process. I think you deserve the benefit of your own experience, repeatedly, throughout your life. You are the descendant and ancestor. Your story matters in profoundly moving ways because it is our collective story.

The one item I would include is a draft of a recipe book my dad gave me years ago. The way I’ve expressed my love in the past was to build an art project with a person I love. My dad’s handwriting alone delights me. His recipes are okay, not remarkable, but they’re my dad’s recipes, and so they matter to me and my family. ︎

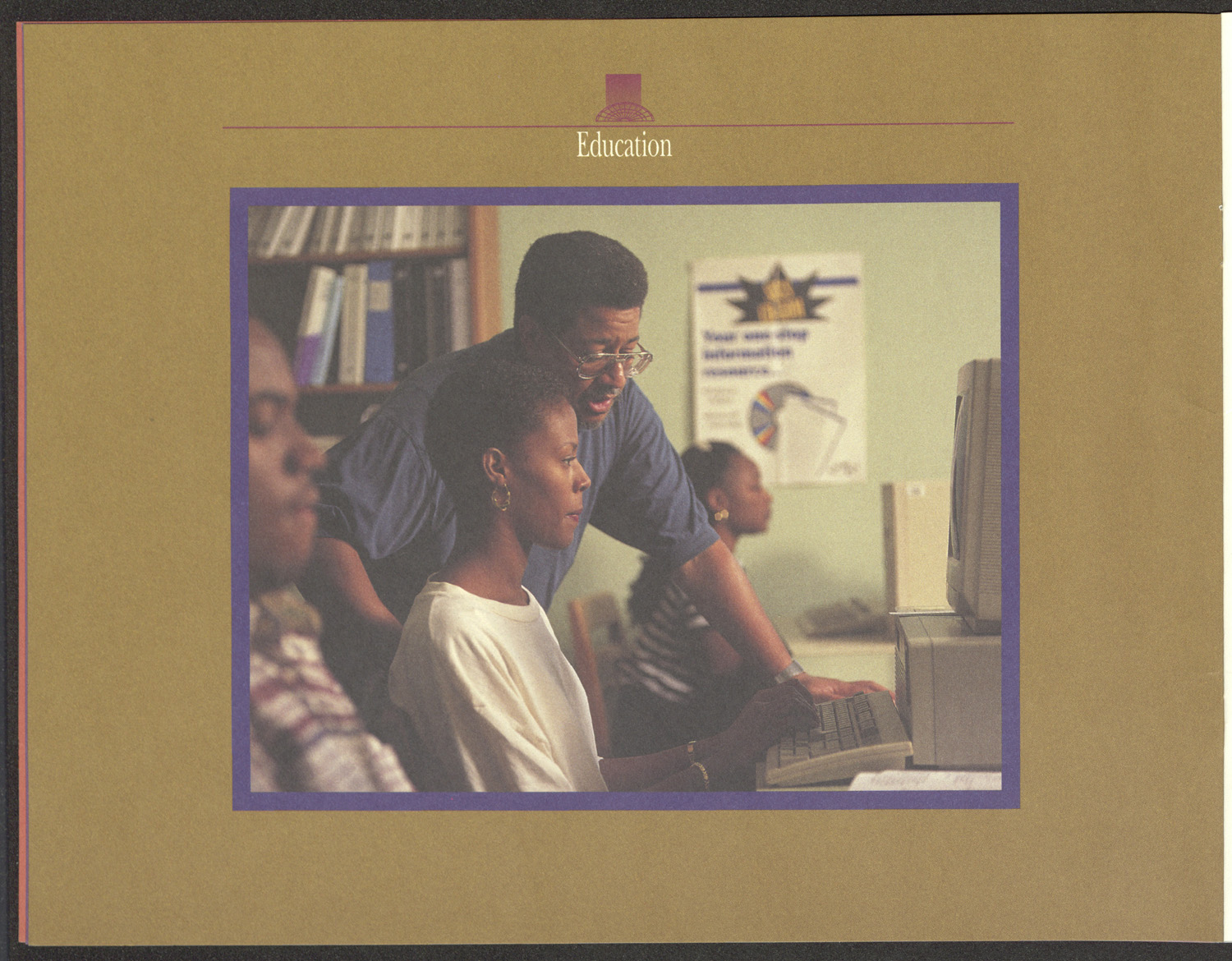

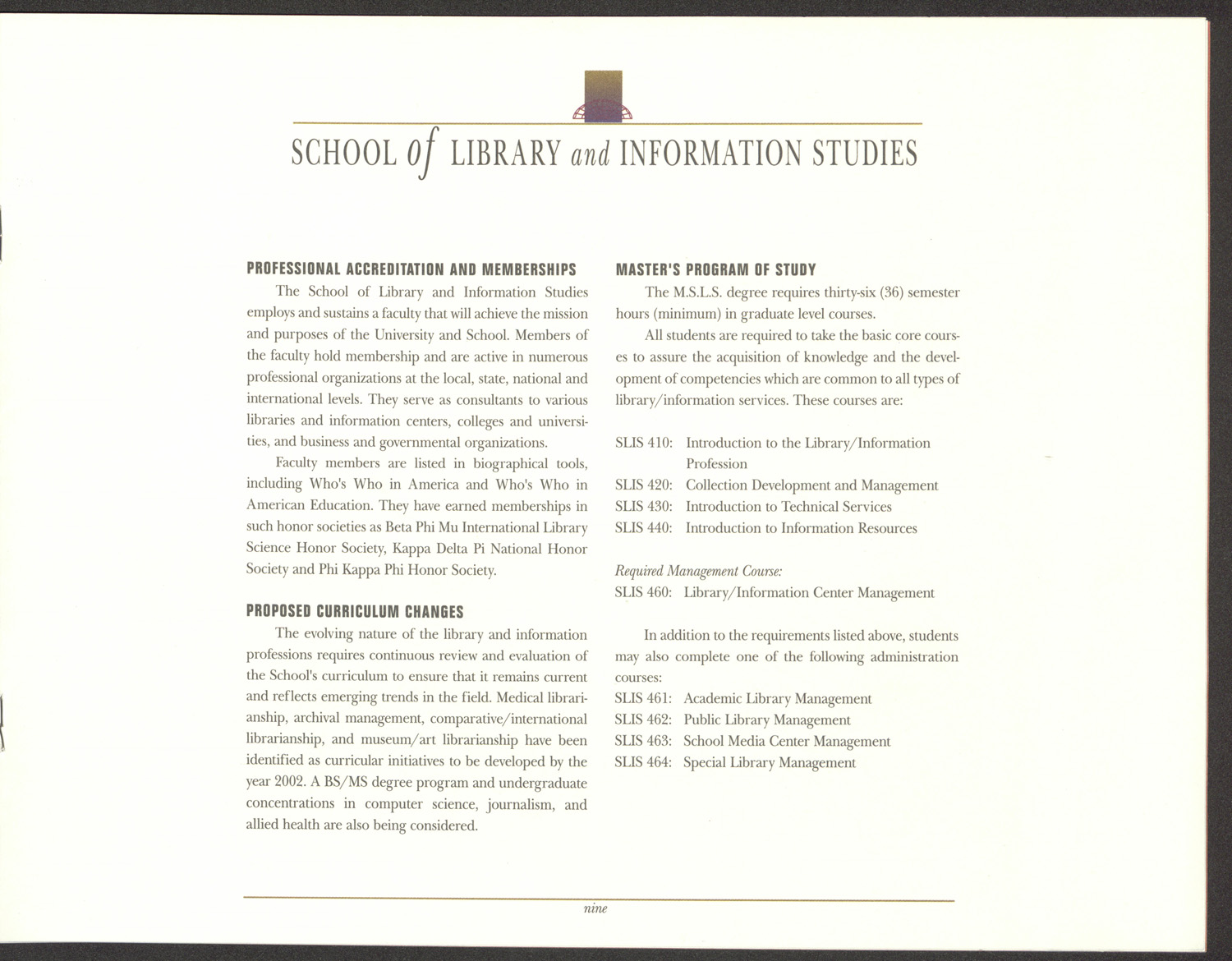

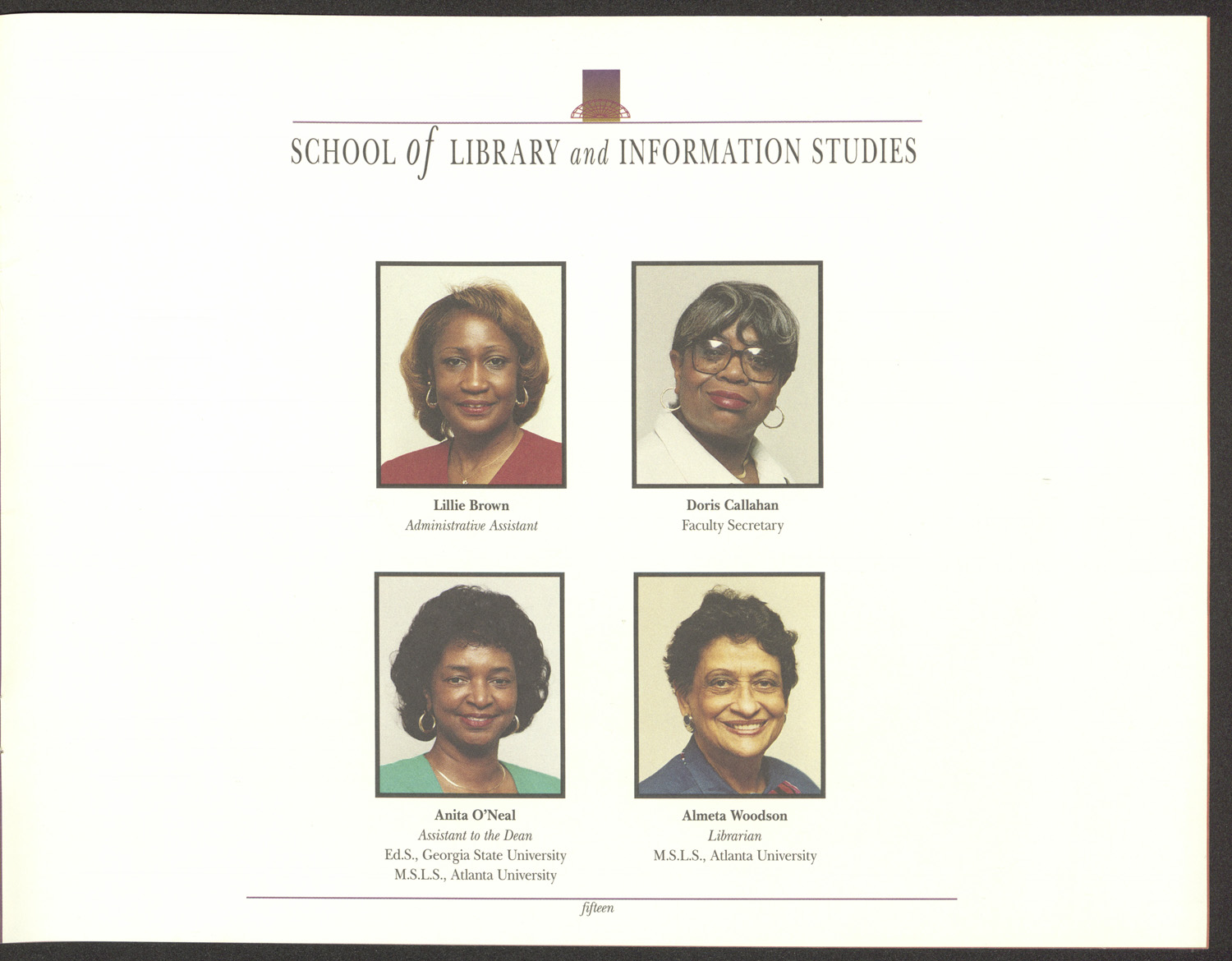

Images: Scans of Clark Atlanta School of Library and Information Science (SLIS) Brochure, circa 1995. GLAM Center for Collaborative Teaching and Learning, Atlanta University Center Robert W. Woodruff Library.

1 Lenk’s Hill was mainly a Germanic neighborhood, and as it became more heavily populated with those who identified themselves as of Polish extraction, it became known as “Kuschwantz,” which means cow’s tail, because it generally followed the path of a railroad line. 2 “take into one's possession or control by force.” the act of recording in a permanent file. Merriam Webster.

Steven D. Booth (he/him) is an archivist, researcher, and co-founder of The Blackivists Collective. He has been with the National Archives and Records Administration since 2009 and currently manages the audiovisual collection for the Barack Obama Presidential Library. He is actively involved in the Society of American Archivists (SAA) and recently served on the governing board of the organization.

Steven D. Booth (he/him) is an archivist, researcher, and co-founder of The Blackivists Collective. He has been with the National Archives and Records Administration since 2009 and currently manages the audiovisual collection for the Barack Obama Presidential Library. He is actively involved in the Society of American Archivists (SAA) and recently served on the governing board of the organization.